Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

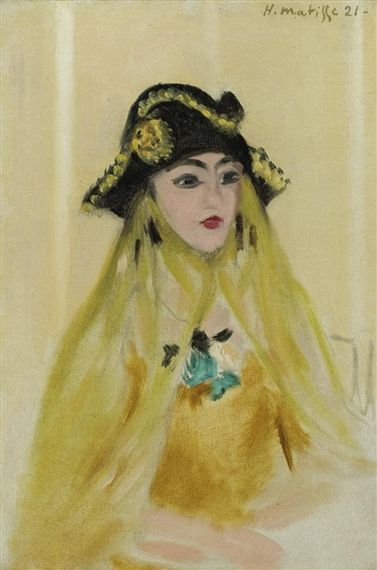

Henri Matisse’s “Venetian Woman En Buste” concentrates an entire world of style, theater, and sensation into a small, bust-length portrait. A young woman faces us frontally. She wears a black, gold-trimmed hat and an airy yellow veil that cascades over her shoulders, pooling into the warm golds of her bodice. A turquoise note near the neckline flares like a brooch or ribbon. Her lips are a clear coral, her brows arched and calligraphic, her gaze steady but reserved. Behind her spreads a pale, breathable ground with no furniture or window to distract. The picture is minimal in parts and luxuriant in effect—an object lesson in how much presence Matisse could conjure with a few tuned tones, a supple contour, and a handful of decisive accents.

A Nice-Period Portrait Of Theatrical Ease

Created during Matisse’s early 1920s Nice period, the work belongs to a cluster of portraits and interiors where he redefined modern harmony. After the upheavals and experiments of the 1910s, he settled on a new classicism: quieter chroma, more lucid drawing, and rooms or half-length figures arranged for poise. The “Venetian” costume names an atmosphere rather than a biography—Matisse often stocked his studio with hats, veils, and shawls that could move a sitter from the ordinary into a realm of symbolic style. In this canvas the costume does not burden the figure; it frees her. The hat’s dark mass and the veil’s luminous spill give the face a stage on which to act with minimal effort.

Composition: A Triangle Held In A Rectangle

The painting’s geometry is simple and satisfying. The rectangle of the canvas is stabilized by three forces: the dark wedge of the hat at top, the two descending planes of the veil at left and right, and the small, bright apex of the mouth and chin. Together they create a triangular scaffolding that anchors the frontality of the pose. The shoulders barely register—hints of curve under the veil—so the eye remains where Matisse wants it: on the calibrated relationship between headwear, veil, and face. Negative space is crucial. The pale background opens around the figure like a halo of air, preventing the black cap from weighing the image down and letting the yellow read as light rather than fabric alone.

The Palette: Black As Color, Yellow As Light

Matisse’s palette is highly economical yet full of temperature shifts. The hat is not a dead black. It carries warmer and cooler passages that respond to the gold ornaments and to the neutral ground around it. The veil is a range of yellows—from canary to honey to gray-washed straw—delivered in layers so thin the weave of the canvas lends them a feathery transparency. Skin is mapped with creamy warms and cool pearls, allowing coral lips and rose in the cheeks to sound clearly without cosmetics-like intensity. A turquoise flourish near the collar is the single high-chroma accent; it throttles the yellow’s warmth and keeps the portrait from smoldering. The harmony is Mediterranean but tempered: sunlight understood as color, not glare.

Brushwork: Transparency, Scumble, And Calligraphy

The surface tells you how it was made. The veil is laid in transparent veils of paint—two strokes that meet and feather rather than a fully modeled textile. The ground is brushed thinly and evenly so that it reads as air and wall at once. The hat’s gold trim is flicked on with short, round touches that remain brush marks rather than embroidered description. Facial features are calligraphic: the brows a single elastic curve, the eyes built from dark commas of upper lash and a gentle shadow below, the nostrils not drawn but implied by a tiny value shift, the mouth a crisp, coral contour that softens instantly at its corners. This candor about facture gives the portrait its life; the viewer senses decisions, not labor.

The Veil As Pictorial Device

In practical terms the veil performs three jobs. It widens the silhouette so the bust fills the rectangle confidently. It transforms the yellow garment into airborne color, turning clothing into atmosphere. And it acts as a diffuser: the face seems to emerge from color the way a figure emerges from light on a stage. Because the veil is painted with so much transparency, it never competes with the facial planes; instead it surrounds them, keeping the image buoyant. The veil is thus both subject and device—an elegant solution to the challenge of making a bust portrait expansive without clutter.

Costume, Venice, And The Studio Imagination

The title’s “Venetian” signals cultural memory more than strict ethnography. Matisse evokes the theater and masquerade associated with Venice—carnival headwear, sumptuous textiles, the play of identity—without copying any particular outfit. In the Nice years he repeatedly explored how a change of hat or shawl could move a sitter across registers: from modern Parisian to odalisque to Spanish or Venetian fantasy. Here the black-and-gold cap and the veil’s pomp suggest ceremony, but the painter’s touch keeps everything light. The result is an image that honors costume as a language of color and shape rather than a catalogue of details.

Drawing: The Living Contour

A flexible line binds the portrait. It is strongest where structure must be felt—the outer brim of the hat, the jawline, the tip of the nose—and almost absent where the veil dissolves into ground. Around the eyes, line is both drawing and makeup; it provides the graphic emphasis that reads as eyeliner while functioning as Matisse’s signature contour. Along the veil’s lower edge, the line thins to a whisper, letting yellow vapor into the background. Because the contour changes weight so responsively, the figure stays alive on the page; she is neither cut out nor melting.

The Face: Presence Without Psychology Theater

Matisse’s portraits during the Nice period resist dramaturgy. The sitter’s expression here is poised, neither coquettish nor distant. The mouth is closed, the gaze level, the head slightly inclined as if the hat’s weight had shifted the balance of the neck. Instead of modeling every muscle, he calibrates color and line to convey calm alertness. The coral of the lips answers the warm cheek; the brows, browsed a touch darker than the hair, contemplate the viewer without inquiry. The refusal to over-describe is not indifference; it is respect for the sitter’s autonomy. She remains herself within the painting’s order.

Texture And Scale: Making A Small Picture Feel Large

Though intimate in scale, the portrait feels expansive, partly because of texture management. Thin paint over a lightly toned ground allows light to circulate through the surface, giving the yellows and flesh a kind of internal glow. The hat and facial features carry the densest pigment, anchoring the top of the picture; the veil and background are thinner, so the bottom and sides seem to breathe. This distribution creates a sense of volume without laborious modeling. The viewer’s eye fills in the rest, and in doing so, enlarges the experience of the image.

The Role Of White And Reserve

One of the portrait’s quiet masterstrokes is its use of reserve—the uninsisted zones of pale ground left to play as color. Between the two yellow streams of the veil, a cool white channel runs down the centerline, subtly articulating throat and bodice while preserving luminosity. At the canvas edges, slips of untouched ground keep the whole image from crowding the frame. White here is not absence; it is the highest note in the chord, necessary for the yellows and blacks to sound balanced.

Comparisons And Dialogues

Set beside Matisse’s earlier “Woman with a Hat” (1905), this portrait shows how far his palette has mellowed while preserving the primacy of color. Instead of fauvist shocks—acid greens, violent reds—he favors a limited scale tuned with precision. In relation to the contemporaneous “Woman in a Hat” and the series of “Spanish” and “Odalisque” studies, “Venetian Woman En Buste” is especially distilled: no patterned carpet, no striped table, only the fundamental trio of hat, veil, and face against air. It foreshadows the late paper cut-outs in its reliance on silhouette and simple, legible shapes, even as it revels in the sensuality of oil’s transparency.

Rhythm And The Viewer’s Circuit

The portrait proposes a reliable path for the eye. We begin at the black hat, where gold rosettes punctuate the brim, then slide down the left veil into the turquoise note at the chest, cross the coral mouth, and rise along the right veil to the opposite rosette. Each loop reveals a new incident: a quick gray shadow under the lower lip, a warmer smudge at the cheekbone, a softened seam where veil meets ground. The rhythm is slow and satisfying, like tracing the contour of a shell; it rewards repeated looking.

Light As Color, Not Effect

Matisse treats light as inherent to pigment rather than as a separate overlay. The yellows are inherently luminous; the ground’s warmth behaves like reflected glow; the blacks are balanced with enough surrounding air that they remain radiant rather than dead. Highlights—on the lower lip, at the brow ridge, on the rosette—are small, specific, and never chalky. Because light is built into the palette, the image stays steady across viewing conditions; its harmony does not depend on a single dramatic flash.

Cultural Echoes And Modern Identity

While the costume evokes Venice, the portrait remains modern in its ethics. The sitter is not a masquerade doll; she is a contemporary person inhabiting chosen style. Matisse’s handling insists on her immediacy: the unfinished edges, the visible brush, the open ground—all signs of a real studio moment rather than a finished salon fantasy. The work thus negotiates between historical evocation and present-tense presence, a balancing act central to Matisse’s portraiture of the 1920s.

Meaning Without Program

The painting offers no allegory. Its meaning resides in the coordination of parts: the firmness of black supported by the buoyancy of yellow, the stable frontal pose animated by floating edges, the particularity of features set within a costume that stands for a larger tradition of festivity and elegance. It is a meditation on how a few colors and shapes, rightly related, can dignify a person and condense an atmosphere.

Why The Image Endures

“Venetian Woman En Buste” endures because it establishes a clear, memorable silhouette and then fills it with gently shifting life. It shows how economy can be sumptuous, how a thin veil of paint can hold as much power as impasto. The portrait is both a study in restraint and a little festival: a black-and-gold hat as crown, a yellow veil as sunlight, a turquoise spark as sea air, and a face that grounds the ensemble. You carry it in memory the way you remember a bright, simple melody.

Conclusion

This small canvas exemplifies Matisse’s Nice-period mastery. With almost nothing—one hat, one veil, a handful of tones—he composes a complete world of poise. The living contour binds it, the transparent yellows aerate it, the blacks dignify it, and a few carefully placed reds and blues quicken it. “Venetian Woman En Buste” proves that the essentials, arranged with care, are enough: color as climate, line as breath, surface as stage, and a human presence that meets us with calm intensity.