Image source: wikiart.org

A Room Flooded with Color

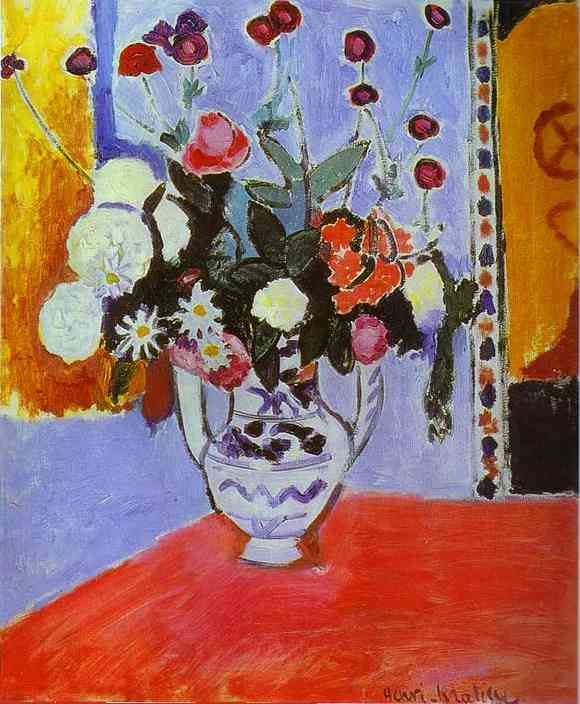

Henri Matisse’s “Vase with Two Handles” (1907) greets the eye like a sudden intake of fresh air. A full bouquet—peonies, roses, daisies, and tight rosebuds—springs from a white jug with elegant twin handles, set on a blazing red tabletop against fields of lilac, gold, and black-dotted ornament. The painting is at once intimate and theatrical: an everyday still life transformed into a stage where color, line, and pattern perform with unapologetic clarity. Seen within the artist’s development, it embodies the moment when the incendiary discoveries of Fauvism crystallized into a calm yet radical decorative order.

The Historical Moment: 1907 and the Afterglow of Fauvism

Two years after the Fauves shocked Paris with their uninhibited palettes, Matisse was consolidating those discoveries. In 1907 he had just returned from North Africa and continued to surround himself with textiles, ceramics, and craft objects collected in markets and studios. These objects were not props; they were partners in an evolving pictorial language that prized surface, rhythm, and the unity of an interior. “Vase with Two Handles” takes the ecstatic color of 1905 and channels it through clear, stable shapes. The result is neither austere nor wild. It’s a poised, modern vision of domestic beauty.

First Encounter: A Bouquet That Refuses to Sit Still

Walk up to the picture and you notice how the bouquet seems to lean toward you, as if drawn by the heat of the red table. The flowers are not naturalistic; they are emblems, each a compact disc or spiral of pigment, ringed with dark line and crisp leaf shapes. The table thrusts forward like a stage, cropped sharply at the bottom edge. Behind the bouquet, a lilac wall, a golden panel at left, and a vertical bead-like border at right create a shallow architecture—a room of color planes rather than measured depth. The whole composition is a conversation between curved forms (handles, petals, leaf ovals) and rectilinear fields (table, wall, panels).

Subject and Motif: A Classical Vessel Made Modern

The two-handled vessel anchors the painting. It summons the memory of Mediterranean amphorae and Renaissance majolica, yet Matisse treats it as a sign rather than an artifact. Its arabesque handles describe near-symmetrical loops; the blue motifs on the white belly are condensed to a few decisive strokes. The vase is not shaded in the academic sense; instead, its whiteness glows by contrast with the crimson table and the lavender wall. In Matisse’s hands, the vessel becomes a neutral center of gravity—cool, pale, and calm—around which the hotter color fields can revolve.

The Architecture of the Composition

The picture is built on a sequence of interlocking rectangles and a central triangle. The red tabletop forms a truncated wedge, its apex pointing to the vase’s foot, while the lilac wall provides a broad vertical field behind. Two warm panels—golden at left and a deeper orangey-red at right—frame the bouquet like theater curtains. At the far right edge, a vertical band of patterned dots acts as a visual hinge, turning the wall into a decorated screen. The bouquet itself resolves into a triangular mass with the apex at the tallest rosebuds. That stable geometry allows Matisse to unleash energetic brushwork in the flowers without sacrificing compositional clarity.

Color as Structure Rather Than Description

Matisse’s palette is limited but potent: vermilion red, lilac-lavender, lemon and ochre, bottle and emerald greens, scoops of white, and decisive black. The color is not used to imitate local tones but to establish relationships. Red and green—complementaries—spar with productive tension between tabletop and leaves. Yellow and violet—another complementary pair—vibrate between the golden panel and the lilac wall. White blossoms and the vase’s body are pitched to high value, catching the eye like lights on a stage. By letting color blocks do the heavy lifting, Matisse renders shadow almost unnecessary. Atmosphere is achieved through adjacency, not through glazing.

Black as a Living Color

The painting demonstrates Matisse’s belief that black is not the absence of color but a hue with its own temperature and force. Black outlines define petals and leaves; a pool of near-black anchors the background to the right. These blacks are not schematic; they play against the bright palette to heighten saturation and sharpen contours. Observe the leaves: many are flat, nearly silhouette shapes of deep green so dark they verge on black, edged with quick strokes that grant them crispness without laborious modeling. The eye reads these as decisive, modern signs for “leaf,” freeing the brush to describe movement rather than botanical detail.

Brushwork and Surface: The Dance of the Hand

The surface is a record of swift, sure decisions. Flowers are laid in with thick, creamy strokes, sometimes loading two colors on the same brush so a single petal splits into rose and white. The lilac wall is scumbled softly, letting flickers of ground show through, which lends air to the backdrop. The golden panel to the left is stabbed with short, warm strokes that suggest a textured textile rather than a flat wall. The red table is opaque and more evenly painted; it functions as a supporting plane, so Matisse cools the brush dance here, letting the eye rest before it springs upward into the bouquet.

Light Without Illusion

There are no cast shadows or carefully modeled highlights, yet the painting glows. Matisse achieves luminosity through value orchestration: the brightest whites are encircled by mid-value lilac and gold; the darkest accents are embedded at the bouquet’s interior and along the right margin. This value scaffold gives the composition legibility at distance. Step back and the flowers read as a single radiant mass; step close and you feel the tactile differences between velvety rose, chalky daisy, and glossy leaf, all conjured with pigment alone.

Pattern, Textile, and the Decorative Ideal

The dotted vertical border on the right and the saffron panel on the left are not literal depictions of walls; they are painterly equivalents of textile pattern. Matisse owned and studied fabrics from North Africa and the Near East. Their ornamental rhythms reshaped his understanding of pictorial space, giving him permission to turn background into active participant. Here, the border of colored beads mediates between the bouquet and the room, lending the right side a syncopated beat that balances the heavier mass of flowers on the left. The overall effect is not of objects in a room, but of a harmonized surface—what Matisse later called “a construction of colored surfaces.”

The Role of the Red Table

The table carries extraordinary responsibility. Its saturated hue warms the entire canvas and thrusts the still life toward the viewer. The diagonal cut at the lower edge denies traditional perspective; instead of receding lines, we have a color plane that asserts itself like a rug. That thrust is tempered by the cool lavender wall, preventing the red from overwhelming the bouquet. Notice how the small shadow-gray oval beneath the vase’s foot secures it without resorting to classical shading. One compact mark is enough to keep the vessel grounded while the surrounding colors sing.

Drawing with Color: Contours that Breathe

The outline of the vessel and of many petals is drawn with a fine, dark stroke, but the most important “drawing” in the painting occurs in the tension between color blocks. Where the red meets the lilac, a crisp edge defines the table; where lilac meets gold, the edge softens, implying a textile without drawing it. The bouquet’s outer contour is wonderfully irregular—buds extend like antennae, leaves form deep scallops—so that the silhouette alone is lively and specific. This breathing contour, part drawn and part painted, keeps the still life from feeling static.

Emotional Tone: Festive Poise Rather Than Frenzy

Despite its bold palette, the picture is not aggressive. It is festive, poised, and generous. The flowers feel freshly arranged but not delicate; they are robust glyphs of life. The domestic setting suggests intimacy—a table, a vase, a corner of patterned wall—but Matisse’s treatment dignifies these ordinary things. The mood is one of abundance without excess, of clarity without chill. The painting offers a sense of well-being that is not sentimental but architectural, crafted through ratio and rhythm.

Dialogues with Other Works

“Vase with Two Handles” belongs to a chain of Matisse interiors that culminates in “Harmony in Red (The Red Room)” and later works such as “The Red Studio.” The blazing tabletop anticipates those immersive fields of color that dissolve traditional depth into decorative continuum. At the same time, the bouquet prefigures the artist’s lifelong return to cut flowers and ceramics, from the Nice-period odalisques surrounded by patterned fabrics to the serene still lifes of the 1940s. Seen alongside contemporaneous canvases like “The Madras” (1907) or “Boy with Butterfly Net” (1907), the painting shows Matisse’s growing confidence in setting bold figure or still-life motif against large, breathing fields of color.

Materiality and Making: What the Eye Can Deduce

Although the painting invites optical pleasure, it is equally a lesson in economy. Matisse likely worked wet-into-wet in the bouquet, allowing petals to pick up and smear neighboring hues, while laying broader planes (wall, table) in separate sessions so they keep their evenness. In several places the white ground peeks through, particularly along leaf edges and in the vase decoration, and these breaths of canvas act like tiny lights. Pentimenti—slight corrections—appear where a bud has been shifted or a leaf widened; they remind us that the calm we perceive is the result of searching adjustments.

Space, Flatness, and the Viewer

Matisse refuses the deep perspective beloved of nineteenth-century still life. Space is shallow but not collapsed; we sense a corner, a table, a wall, yet the painting reads primarily as an orchestrated surface. This duality invites a special kind of looking. First your eye participates in the surface pattern—red against lilac, dotted border against flat panel—then it briefly imagines volume in the flowers and vase, only to return to the plane. This back-and-forth is pleasurable, like breathing. It is also a principle of modern painting: to acknowledge flatness while allowing the imagination to create depth.

The Vase as a Figure

Consider the vase as a human surrogate. Its two handles curve like arms akimbo, its round belly like a torso, its narrow foot like a poised stance. The bouquet becomes a kind of head-dress or hair, and the entire ensemble reads as a stylized figure holding court on the red stage. Whether or not Matisse intended this, it helps explain why the composition feels ceremonial. The still life is not a pile of things; it is a single, dignified presence.

Color Psychology and the Senses

The harmony of red, lilac, and gold activates both warmth and coolness. Red offers bodily heat and appetite; lilac brings perfume and air; gold supplies sunlight’s residue. Greens and blacks carve structure, while whites deliver clarity. The bouquet’s variety—tight buds, open rosettes, daisy disks—suggests a choreography of textures. You can almost sense the weight of the vase, the coolness of the table under a palm, the slight give of petals. Matisse taps sight to provoke tactile and even olfactory imagination.

Why the Image Feels Modern Today

“Vase with Two Handles” feels contemporary not because of subject but because of method. Its bold color fields could sit comfortably beside mid-century abstraction; its ornamental border anticipates the flat graphics of design and illustration; its confident outlines echo the clarity of digital icons. Yet the painting never becomes schematic. It breathes, because Matisse marries bold decisions to small, humane nuances: a softened edge here, a half-mixed stroke there, a flick of black that turns a mass into a living leaf.

What to Look For in Person

If you encounter the painting in a gallery, try three distances. From across the room, note how the red plane vaults forward and the bouquet locks the composition together. At a middle distance, watch how the dotted border at right quietly counters the weight of the flowers. Up close, trace the journey of a single stem from base to bud; see how Matisse refuses to describe every leaf vein and instead composes with a sequence of deliberately shaped strokes. This tiered viewing reveals how unity emerges from micro-decisions.

The Painting’s Gift

Matisse famously wanted his art to offer a soothing, balanced place—“like a good armchair”—but he never equated rest with blandness. “Vase with Two Handles” exemplifies that ideal. It restores attention by simplifying the world into planes and rhythms, yet it keeps surprise alive in every edge and accent. The picture teaches the eye to move slowly, to relish relations, to trust that beauty can arise from the most domestic scene: a jug, a tabletop, a handful of flowers, and light.