Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

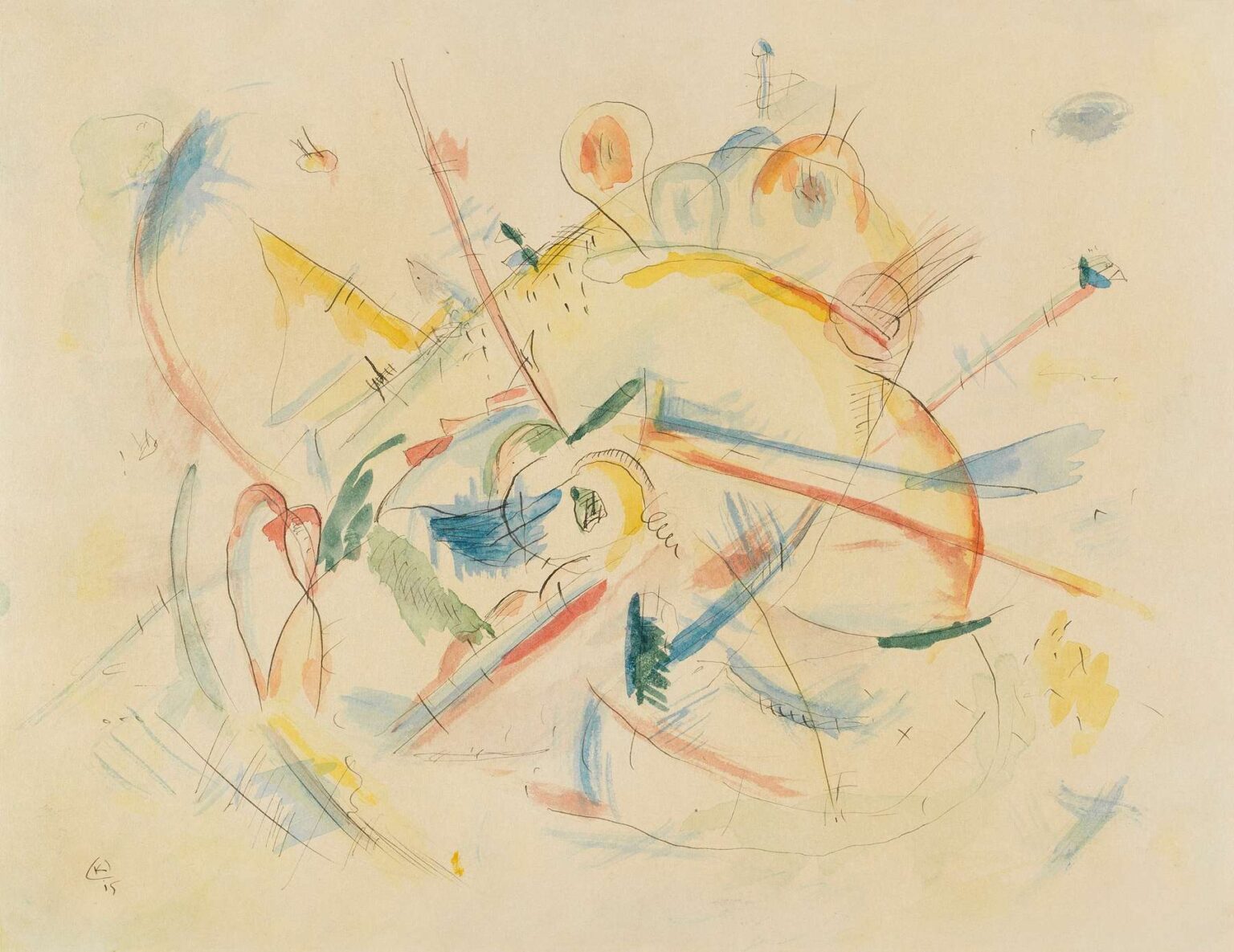

In this untitled watercolor and pencil drawing created by Wassily Kandinsky in 1915, we encounter a masterful interplay of line, color, and space that marks an important moment in the artist’s journey from representational motifs to pure abstraction. Executed on a warm ivory ground, the composition unfolds as a dynamic network of swirling arcs, intersecting diagonals, and delicate hatchings, all punctuated by soft washes of yellow, blue, green, and red. Far from an arbitrary arrangement of marks, each stroke and hue resonates with Kandinsky’s evolving synesthetic theories and his quest to translate inner experience into visual form. This analysis will explore the historical circumstances that shaped Kandinsky’s work in 1915, unpack the formal strategies he employs in this untitled piece, assess its technical execution, and consider its emotional and symbolic dimensions within the broader context of the artist’s spiritual abstraction.

Historical and Personal Context in 1915

By 1915, Europe was in the throes of the First World War, and Kandinsky, though spiritually aligned with the avant‑garde of Munich, found himself internally exiled by the turmoil engulfing the continent. Having returned to Russia briefly in 1914, he grappled with dislocation from his artistic comrades in Germany and a growing restlessness to find a new visual language that transcended the external chaos. His paintings and works on paper from this period reflect a tension between lingering elements of figurative allusion and a burgeoning embrace of pure abstraction. Kandinsky’s belief in art’s spiritual mission—art as an inner necessity rather than a simple reflection of outward reality—guided his practice. This untitled drawing, executed in 1915, emerges precisely at this crossroads: it retains echoes of structural composition but departs entirely from recognizable subject matter, pointing instead toward melody, resonance, and the painterly equivalent of musical improvisation.

Synesthetic Foundations and “Inner Necessity”

Central to Kandinsky’s creative philosophy was the notion of synesthesia—the capacity for one sensory modality to evoke another. He famously wrote about hearing colors and seeing sounds, positing that certain lines and hues correspond to musical notes, rhythms, and timbres. In his lectures and writings of the early 1910s, Kandinsky articulated “inner necessity” as the driving force of authentic creation: only forms that arise organically from the artist’s inner life possess true vitality. In this untitled drawing, the artist sets aside narrative obligations and allows pure line and color to speak. The large sweeping arc, for instance, functions as a deep bass gesture, while the fine pencil hatchings dance like quicksilver piccolo flourishes. Subtle washes of watercolor add harmonic depth akin to string undertones in a chamber ensemble. Through this synesthetic mapping, Kandinsky transforms a blank sheet into a canvas of spiritual and sensorial resonance.

Composition and Structural Dynamics

At first glance, the drawing appears to be a whirlwind of intersecting marks. A broad, gently curving arch sweeps from the lower right quadrant toward the upper left, providing the primary directional thrust. This arch bisects the composition, dividing the sheet into two energetic fields: one above and one below the curve. Diagonal lines cut across the arc at varying angles, establishing a sense of tension and cross‑current movement. Near the center, a circular form emerges through pale yellow wash, its circumference delineated by thin pencil strokes that oscillate between precision and feather‑light suggestion. Radiating from this focal circle are short linear dashes and softly rendered loops that evoke echoes or overtones. In the upper portion of the sheet, a cluster of loose, cloudlike shapes washes in palest orange and blue, floating as ephemeral counterpoints to the more robust central gestures. Below, a rectangular lattice of pencil hatchings suggests a foundation or grid, grounding the composition’s upper exuberance. This architectural framework of arcs, diagonals, circles, and hatchings achieves a dynamic equilibrium: no single element dominates, yet the viewer’s eye is guided in a spiral journey from the periphery toward the luminous center.

Color and Tonal Modulation

Although Kandinsky is celebrated for his bold color palettes, in this 1915 drawing his application of watercolor remains nuanced and restrained. The warm ivory ground serves as an omnipresent backdrop, its undertone lending cohesion to every mark. The largest color note—a wash of gentle yellow—occupies the central circular form, imparting a luminous glow. Surrounding this core, strokes of sky blue, mint green, and pale vermilion punctuate key pivot points: the crest of the main arc, the tips of diagonals, and the soft halos above the central mass. These colored accents are applied sparingly, never saturating the paper to the point of opacity. Instead, they seep into the wash, revealing the paper’s texture and allowing underlying pencil lines to peek through. This interplay of transparent washes and precise graphite renders the drawing both airy and structurally sound. The tonal variances—lighter in the upper cloud‑like shapes, richer in the central circle—create a subtle chiaroscuro effect, further animating the formal interplay.

Line Quality and Gesture

Kandinsky’s line work in this untitled piece ranges from bold and muscular to whispering and filigreed. The main arc is drawn with a confident, curving stroke of pencil enhanced by a broad wash; its edge remains slightly uneven, indicating the artist’s hand in motion. Diagonals are more rigid, carved with ruler‑like exactitude, as if serving as the composition’s load‑bearing beams. In contrast, dozens of shorter hatchings and cross‑hatchings—some as fine as a spider’s thread—are executed with deliberate irregularity, suggesting organic growth or whispered undercurrents. Loops of pencil, drawn almost in a single breath, skim the voids between larger forms and evoke delicate musical embellishments. At times, Kandinsky allows the pencil to lightly scratch the paper, leaving only the briefest trace of gesture; these barely perceptible marks heighten the drawing’s sense of spatial depth and mystery. Together, the varied line qualities create a polyphonic texture: some voices roar with decisiveness, while others murmur and intone.

Rhythm and Visual Tempo

One of the hallmarks of Kandinsky’s abstraction is an implied rhythmic pulse, and this drawing exemplifies it. The eye is drawn along the sweeping arc, then deflected by the diagonals cutting across it, before resting in the circular nucleus. From there, attention radiates outward to the cluster of cloud‑like washes and the grid of hatchings below. Each form introduces a distinct temporal rhythm: the arc unfolds slowly and grandly, the diagonals pierce swiftly, the central circle pulses gently, and the hatchings vibrate like rapid drum rolls. This sequence establishes a cyclical tempo, inviting sustained contemplation and re‑entry. Moreover, the colored accents function as rhythmic markers—red on the arc’s crest like a snare drum snap, green on a diagonal point like a pizzicato pluck, blue in the grid like a bass drum thump. Through this visual tempo, Kandinsky transforms pictorial space into a living, breathing concert of forms.

Spatial Ambiguity and Depth

Despite its two‑dimensional medium, the drawing conveys an evocative sense of depth without relying on conventional perspective or shading. Overlapping elements—such as the main arc passing in front of the central circle, and certain diagonal lines receding behind pale washes—establish spatial layering. The varied opacity of watercolor washes allows some forms to appear recessed into the ivory ground, while stronger pencil strokes bring others to the forefront. The interstitial emptiness between lines and washes creates pockets of “air” or negative space, through which one glimpses hints of underlying marks. This network of transparent and opaque zones produces an almost topographical landscape, where forms hover at different perceived distances. The overall effect is one of controlled spatial ambiguity: the viewer senses a three‑dimensional realm, yet no single vanishing point or horizon line is ever asserted.

Technical Execution and Materials

Kandinsky’s mastery of watercolor and pencil is evident throughout the drawing. He works on fine‑to‑medium textured drawing paper, whose ivory tone smoothly absorbs pigment and graphite. The artist begins by sketching primary structural lines—likely the broad arc and intersecting diagonals—often using a softer graphite that adheres well under subsequent washes. He then applies watercolor with both large‑flat and slender round brushes, modulating pigment load to achieve gradients and blooms. The washes remain fresh and unblended, indicating a rapid, instinctive application. Once dry, Kandinsky returns with pencil to accentuate edges, introduce hatching, and add delicate scribbles. The precision and confidence of these final pencil gestures suggest a practiced hand unafraid of leaving spontaneous marks. The integration of wet and dry media on a single sheet demonstrates Kandinsky’s fluency across disciplines and his willingness to harness the unpredictable qualities of watercolor alongside the exactitude of pencil.

Symbolic and Spiritual Dimensions

At a symbolic level, the composition can be read as a microcosm of spiritual ascent and inner revelation. The central circle, aglow with yellow, evokes a radiant core or cosmic nucleus—perhaps signifying the artist’s conception of a universal spirit. The sweeping arc might represent the arc of consciousness or the trajectory of the soul, while the cluster of cloud‑like shapes above suggests ephemeral thoughts or divine emanations. The descending grid of hatchings below could symbolize earthly structures or the gravity of material existence. Through the interplay of these symbols, Kandinsky stages a journey from the mundane to the transcendent, affirming his belief that abstract forms can convey profound metaphysical truths. Far from being arbitrary marks, the drawing’s shapes function as signposts toward spiritual terrain.

Relation to Kandinsky’s Broader Oeuvre

This 1915 untitled drawing sits at a pivotal juncture between Kandinsky’s late Expressionist work—still tinged with figurative echoes—and his fully abstract canvases of 1916–1917. In earlier works, he often combined stylized houses, towers, and figurative motifs with abstract elements. By 1915, however, he had resolved to abolish representational references altogether, trusting in pure form to carry meaning. The drawing’s emphasis on line, color accents, and spatial layering prefigures his seminal oil painting Composition VII (1913) and the later Improvisations and Compositions of 1916. Yet in the intimate scale and immediacy of watercolor and pencil, the piece reveals a more spontaneous, exploratory side of Kandinsky’s practice. It acts as a laboratory for ideas that would later be monumentalized on canvas.

Emotional and Aesthetic Impact

Encountering this untitled drawing elicits a complex blend of emotions. One may feel uplifted by the luminous central glow, energized by the dynamic arcs and diagonals, and soothed by the gentle chromatic accents. The drawing’s evocative ambiguity encourages personal projection: some viewers sense cosmic dance, others perceive elemental forces at play. The absence of concrete imagery liberates the imagination, inviting each person to “hear” its visual music in unique ways. Kandinsky prized this open‑endedness, believing that abstract art achieves its greatest potency when it awakens the viewer’s own spiritual and emotional resources. This drawing, with its balanced tension and luminous harmony, accomplishes precisely that.

Legacy and Influence

Though less widely known than his large oil paintings, Kandinsky’s works on paper from 1915 remain vital to understanding the evolution of abstract art. This untitled drawing exemplifies the porous boundary between media—its lessons have informed subsequent generations of painters, illustrators, printmakers, and graphic designers. The synergy of confident line work and atmospheric wash has inspired countless artists to pursue hybrid techniques. Moreover, Kandinsky’s philosophical writings, which underpin these visual experiments, continue to shape contemporary discourse on the emotional and spiritual dimensions of abstraction. In galleries and scholarly texts alike, his drawings stand as testament to art’s ability to channel the invisible forces of inner necessity and to forge resonant connections between creator and viewer.

Conclusion

This untitled 1915 drawing by Wassily Kandinsky offers a profound glimpse into the artist’s masterful synthesis of synesthetic theory, technical prowess, and spiritual aspiration. Within its seemingly spontaneous swirl of arcs, diagonals, circles, hatchings, and color accents, Kandinsky charts a path toward pure abstraction—one that privileges inner resonance over external resemblance. The drawing’s formal complexity, emotional depth, and technical refinement make it a pivotal waypoint in Kandinsky’s journey and an enduring exemplar of visual music. Over a century after its creation, it continues to inspire and challenge viewers, affirming the timeless potency of abstract art to convey the intangible currents of the soul.