Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

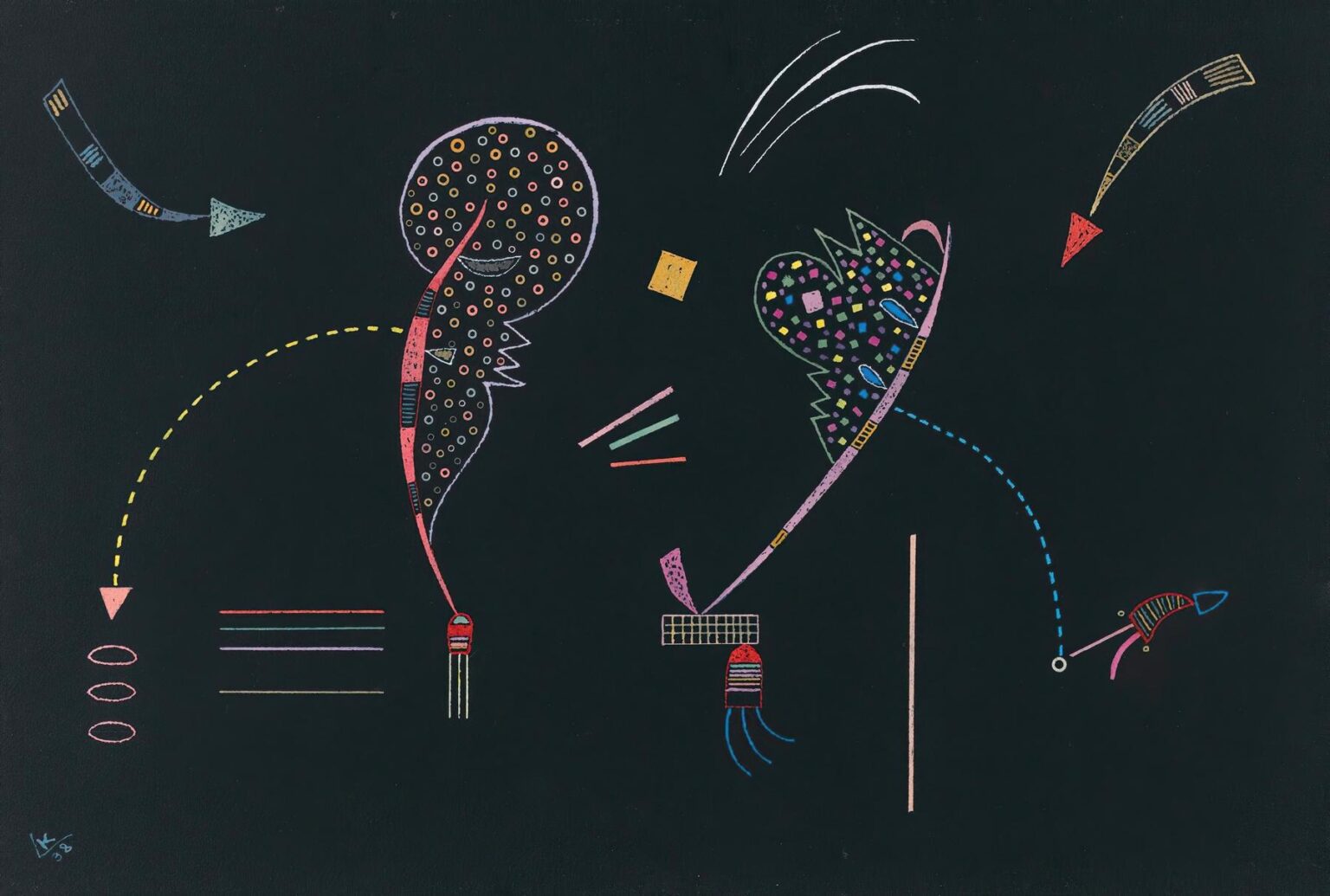

Wassily Kandinsky’s Two Sides (1938) stands as a masterful exploration of duality, tension, and harmony within the realm of late modernist abstraction. Rendered on a deep, near‑black ground, the painting features two organic, wing‑like forms—each bristling with intricate dots, dashes, and miniature geometric accents—poised in mirrored opposition. These shapes appear suspended in space, connected by gently arcing dashed lines that suggest unseen forces of attraction or repulsion. Surrounding them are a series of spare linear motifs—vertical bars, curving arrows, and diminutive rectangles—each contributing to the work’s dynamic equilibrium. Created near the end of Kandinsky’s tenure at the Bauhaus and on the eve of his eventual relocation to France, Two Sides distills the artist’s lifelong investigations into color, form, and spiritual resonance into a concise, enigmatic tableau. Through this painting, Kandinsky invites viewers to contemplate the interplay of opposing energies and the potential for unity within contrast.

Historical Context

By 1938, Kandinsky had weathered decades of radical artistic change, from his early symbolist landscapes to the explosive abstractions of the Der Blaue Reiter and the disciplined geometry of his Bauhaus period. The closing years of the 1930s found him at a crossroads: political unrest in Germany forced him to leave the Bauhaus in 1933, and he settled in Neuilly‑sur‑Seine, France, where he continued to teach and paint. Two Sides emerges from this period of transition, bearing the imprint of Kandinsky’s mature style—one characterized by clarity of line, precision of form, and a deepening emphasis on spiritual symbolism. The looming threat of war infused his work with an undercurrent of tension, while his commitment to abstraction remained unwavering. In this context, Two Sides can be seen as both a reflection on the fractured world around him and a testament to the sustaining power of artistic harmony.

Kandinsky’s Late Style

Kandinsky’s late style is distinguished by a move toward pared‑down compositions, in which every element carries heightened significance. Gone are the riotous color fields and overlapping forms of his early abstractions; instead, forms attain a crystalline simplicity even as they retain expressive nuance. Two Sides exemplifies this evolution. The two main organic shapes, though complex in their internal patterning, possess a singular contour that reads almost as a silhouette. Kandinsky’s palette narrows to stark contrasts—vibrant pinks, delicate greens, electric blues, and warm yellows stand out against the black ground—allowing color to function as a pure signal rather than as part of a broader chromatic tapestry. Fine linear accents—so crucial to his Bauhaus work—reappear here in a more restrained fashion, guiding the viewer’s gaze without overwhelming the central forms. In their geometry and restraint, these late paintings encapsulate Kandinsky’s belief in abstraction as a vehicle for spiritual clarity.

Formal Composition

The compositional architecture of Two Sides revolves around bilateral symmetry tempered by subtle variances. The two principal shapes rise from vertical stems—one crowned by three slender blue filaments, the other by a small red grid—suggesting living organisms or totems. Their voluminous heads, dotted with multicolored circles or tiny squares, tilt toward the canvas’s center, as if engaged in silent dialogue. Between them, a sweeping dashed arc in yellow bridges the gap, while a counter‑arc in blue reciprocates on the opposite side. This dual‑arc motif unites the figures within a loose circular framework. Additional elements—three concentric ovals in pink, a trio of parallel red, green, and yellow bars, a solitary vertical beige stripe—are strategically placed to balance weight and establish a rhythmic pulse. The interplay of symmetry and variation, of central focus and peripheral accents, creates a sense of poised movement akin to a carefully choreographed dance.

Use of Color

Color in Two Sides functions both structurally and expressively. The deep black ground recedes, allowing vibrant hues to project outward with startling clarity. Within each organic form, Kandinsky employs a dense field of tiny dots—pink, yellow, green, and blue—that shimmer against the dark backdrop, suggesting starlit skies or microscopic life. The left form’s dots are predominantly circular, while the right’s are square, introducing a subtle textural contrast. The connecting dashed lines—one yellow, one blue—carry color as a directional force, guiding the eye across the canvas in graceful arcs. Linear accents in coral red, soft peach, and mint green provide further color counterpoint, preventing the composition from falling into monotony. By isolating each hue into specific shapes and lines, Kandinsky achieves a luminous vibrancy reminiscent of neon signage, even as he preserves the painting’s contemplative mood.

Shape and Line

Central to Two Sides are Kandinsky’s characteristic explorations of shape and line. The organic contours of the paired forms evoke living entities—wings, leaves, or abstracted avian heads—imbued with both elegance and otherworldliness. Their interiors, crisscrossed by tiny marks, suggest inner complexity and hidden rhythms. In contrast, the painting’s peripheral elements are sharply geometric: arrows composed of segmented stripes, a vertical stripe that stands like a staff, and horizontal bars that recall musical notation. These linear components do not merely decorate; they resonate with the central forms, articulating invisible connections and articulating spatial relationships. Lines pivot between thick and thin, solid and dashed, imparting a sense of sonic modulation, as if the painting itself were humming with inaudible frequencies. Through this interplay of organic and geometric, Kandinsky conveys his conviction that line is the visual equivalent of melody.

Spatial Dynamics

Although Two Sides eschews traditional perspective, it generates a vivid sense of spatial interplay. The black ground acts as a field of infinite depth, within which the colored forms appear to hover like cut‑outs. The overlapping of arcs, the layering of dots over flat color, and the placement of linear motifs at varying vertical positions create a multi‑layered effect, suggesting foreground, middleground, and background. The two central shapes, though aligned on a common horizontal axis, occupy slightly different planes—one jutting forward, the other receding—accentuating their dialogue. Peripheral arrows and lines extend beyond the main field, as if pointing to realms outside the canvas, while the solitary circles at the lower left hint at gravitational pull. Through this orchestration, Kandinsky invites viewers to experience the painting as a three‑dimensional space collapsed onto a flat surface, rich with imaginative depth.

Symbolic Interpretation

Kandinsky’s abstractions were always imbued with symbolic potential, and Two Sides is no exception. The mirrored forms can be read as embodiments of duality: yin and yang, night and day, masculine and feminine, or the conscious and unconscious mind. Their tender inclination toward each other suggests reconciliation, communion, or the alchemical union of opposites. The yellow and blue arcs link these entities, evoking cycles of renewal and the passage of time. The minute dots within each shape might represent individual souls or energetic particles, congregating to form a greater whole. Linear markers—arrows and bars—could signify directions of thought or spiritual pathways. While Kandinsky resisted fixed interpretations, he believed in the power of abstract form to trigger inner associations. In Two Sides, the painting becomes a mirror for the viewer’s own dualities, inviting a contemplative exploration of balance and transformation.

Texture and Technique

Executed in gouache and ink, Two Sides showcases Kandinsky’s mastery over diverse materials. The black ground, likely achieved through dense gouache, offers a velvety surface against which colored inks glow. The tiny dots and squares appear to be applied with a fine brush or pen, their precision suggesting patient, meditative labor. Dashed lines are evenly spaced, betraying a steady hand and a keen sense of rhythm. The luminous hues—particularly the bright pinks and electric blues—retain a translucency that hints at layering, as if each mark were laid over a subtle wash of color. This play of opacity and transparency lends the work a jewel‑like quality, where shapes catch light differently depending on viewing angle. Kandinsky’s technique here balances the spontaneity of gestural mark‑making with the control of geometric order, producing a tactile surface that invites close inspection.

Viewer Interaction and Emotional Resonance

Encountering Two Sides, viewers are drawn into an active dialogue with the painting’s forms and colors. The eye oscillates between the two mirrored shapes, tracing the dotted patterns and following the arcing dashed lines. Peripheral arrows and stripes beckon, suggesting directions for further exploration. Emotionally, the painting can evoke a sense of intrigue and serenity in equal measure. The luminous colors against the black ground create a feeling of depth and mystery, while the balanced composition offers a reassuring sense of order. Some may sense a quiet tension in the mirrored forms’ near‑touching contours, as if witnessing an intimate encounter. Others might focus on the rhythmic beats of the dots, experiencing a meditative calm. By resisting literal imagery, Kandinsky opens the door for personal projection, allowing each viewer to complete the painting’s narrative through their individual emotional lens.

Legacy and Influence

Though overshadowed by Kandinsky’s more monumental works, Two Sides represents a distilled essence of his late‑career abstraction. Its precise economy of means and contemplative tension can be seen echoed in the work of post‑war abstract artists who sought purity of form—such as Ellsworth Kelly’s minimalist shapes or Agnes Martin’s subtle grid‑structures. The painting’s emphasis on duality and symbolic resonance foreshadows later explorations in conceptual art, where binaries and dialectics became central themes. Kandinsky’s integration of organic contour with geometric precision also paved the way for generative artists who blend algorithmic form with human intuition. Two Sides, in its elegant sparseness, remains a touchstone for anyone investigating how abstract form can articulate complex emotional and spiritual dynamics.

Conclusion

Two Sides by Wassily Kandinsky stands as a testament to the enduring power of abstraction to convey duality, connection, and inner harmony. Through its interplay of mirrored organic shapes, vibrant color accents, and nuanced linear motifs, the painting invites viewers into a space of contemplative equilibrium. Its balanced composition, refined late‑style vocabulary, and subtle symbolic undercurrents exemplify Kandinsky’s lifelong conviction that form and color can resonate with the soul. Created during a period of personal and political upheaval, Two Sides affirms abstraction’s capacity to transcend external turmoil and articulate universal truths. As viewers trace its dotted patterns and follow its arcing lines, they partake in a silent dialogue that bridges opposites and reveals the unity at the heart of contrast.