Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction: A Double Study Of Presence And Dignity

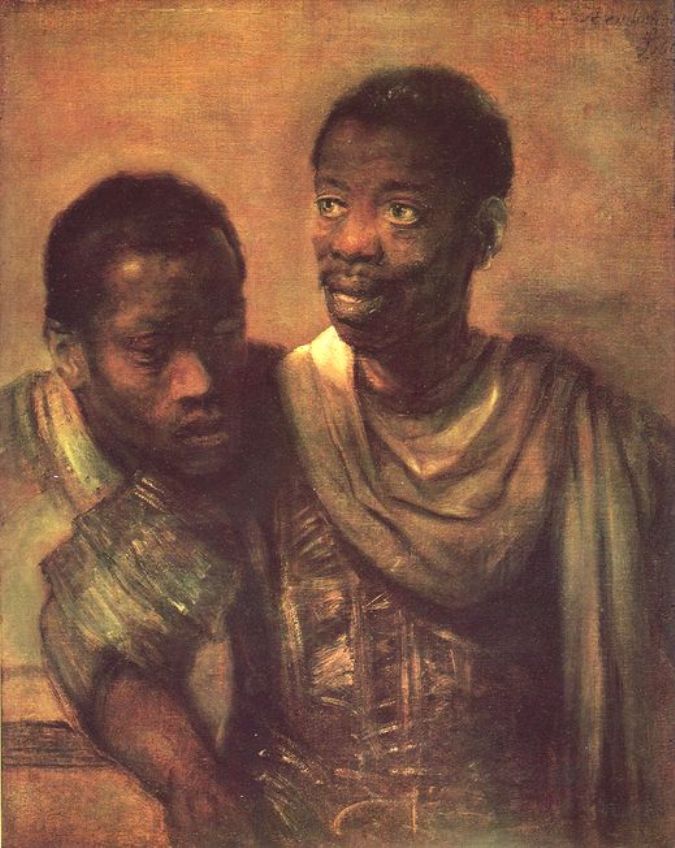

Rembrandt’s “Two Negroes” (1661) is a compact masterwork of observation, empathy, and painterly intelligence. The painting presents two Black men at half length, one leaning in from the left with eyes lowered, the other upright and forward, his gaze lifted with a quiet, alert warmth. Their shoulders touch. Cloaks and drapery wrap the torsos in Rembrandt’s habitual earth tones, while the faces and hands gather the light. The historical title reflects seventeenth-century Dutch terminology; today the work is most fruitfully approached as a humane, searching portrait of two individuals who were part of Amsterdam’s diverse community. Rather than trope or curiosity, they are rendered as people with inner lives—thoughtful, tired, hopeful, amused—each holding the viewer’s gaze in a different register.

Historical Context: Amsterdam, Global Trade, And Late Rembrandt

By 1661 Rembrandt was deep into his late period. He had weathered bankruptcy, suffered family losses, and worked increasingly for patrons who sought the profound interiority of his mature style. At the same time, Amsterdam was a maritime hub whose economy and households were entangled with the Atlantic and Indian Ocean worlds. People of African descent lived in the city as sailors, servants, artisans, and free residents. Rembrandt drew and painted Black sitters throughout his career, from quick chalk studies to finished canvases. In these works he resists exoticism, integrating his models into the same field of attention he brings to apostles, scholars, and family members. “Two Negroes” belongs to this humane practice: a late-style double portrait where the painter’s regard is the central subject.

Composition: A Conversational Diptych In One Frame

Rembrandt composes the canvas as a quiet binary. The left figure inclines, head lowered, forming a diagonal that leads the eye toward the chest of the right figure. The right figure, more vertical, also turns three-quarters to us and slightly away, creating a counterthrust that stabilizes the group. The two heads form an oblique pairing: one duskier, submerged in shadow; the other more fully illuminated. This asymmetry animates the picture without creating competition. We sense sequence rather than conflict, as if their expressions were successive thoughts in one conversation.

Clothing contributes to the compositional weave. The broad shawl that crosses the right sitter’s chest cascades diagonally, echoing the lean of his companion and uniting the two into a single mass. Elbows and forearms, lightly indicated, make a low platform on which the heads and shoulders rest. There is no stage architecture, curtain, or still life to assert context. The setting is the painter’s air—a warm, porous ground that keeps attention on faces and the relationship between them.

Chiaroscuro: Light As Regard

The light that animates the work is the late Rembrandt type: small in scale, humane in temperature, directed like a hand. It enters from the upper left, sliding across the left sitter’s brow before spending itself more fully on the right sitter’s face and drapery. This allocation of light is not hierarchical; it is observational. The left man’s lowered head naturally shades his features; the right man’s uplift turns his brow and cheek to the source. The result is a subtle drama of attention. We peer to know the left figure; we bask in the right figure’s presence.

Shadow never dehumanizes. In Rembrandt, darkness is privacy, not erasure. The left sitter’s features—nose ridge, lips, a tense line along the cheek—come forward through half-tones that are as carefully tuned as the bright planes opposite. The right sitter’s eyes, moistened by minute highlights, hold that quivering Rembrandt light that suggests thought more than glare. The total effect is a chiaroscuro of regard: we feel the painter’s care as much as we see the figures.

Palette And Tonal Harmony: Earth And Ember

The coloristic orchestration is restrained and warm. Umber, raw sienna, and muted olive build the garments and ground; honeyed ochres and subdued reds articulate flesh; a pale, dusty gold lifts the right sitter’s shoulder drapery. The left side of the composition is cooler, moving toward dusky greens; the right warms into amber, which catches light like an ember. Because chroma is limited, value and temperature do the expressive work. A cooler gray lives in the left sitter’s eye socket, tightening his mood; warmer ochres bloom on the right sitter’s cheek, amplifying his openness. These shifts are not decorative; they are ethical choices that insist on individuality.

Surface And Brushwork: Touch That Thinks

Late Rembrandt lets the surface keep the record of looking. Clothing is dragged and scumbled, leaving ridges that catch real light and read as lived fabric. The metal glints at the right figure’s chest—perhaps a clasp or element of armorlike costume—are made with quick, assertive strokes planted atop darker grounds, a shorthand that feels true because it is confident. In the faces the paint is more various: thin veils unify planes; small, decisive touches lock down the crease on a cheek or the glint on a lip. The hair of both figures is managed with different tact—tighter, shorter marks for the left sitter’s curls; a softer halo for the right—another way Rembrandt individuates without fuss.

The Left Sitter: A Closed Circuit Of Thought

The man on the left leans in, head bowed, eyes down or nearly closed. His expression is inward. The set of the mouth, the little tightening at the outer corner, the weight under the lower lid—these are signs of fatigue or sobriety, perhaps even listening. The shoulder he leans upon, whether a parapet or his companion’s arm, gives the pose a human scale. Rembrandt keeps the paint here quiet—subdued color, tighter value range—so the figure feels cohesive and private. It is a risky restraint that pays off: we want to look longer, to grant him the time his expression asks for.

The Right Sitter: A Lifted, Luminous Presence

The right figure offers contrast: chin raised, eyes moist, lips parted in a faint, ambiguous smile. He is not grand; he is alive. The light that touches his cheek and brow spills to the draped shawl at the collarbone, where a small spray of highlights runs like a chain of notes. The modeling of the forehead—small planes at the temple, soft transition above the brow—creates an openness that reads as receptivity. His body, slightly turned from us, gives the face room to exist without performance. If the left sitter is inward turned, the right is outward turned, and together they create a full human chord.

Relationship And Narrative Without Anecdote

Rembrandt offers no story beyond what we can infer from posture and proximity. The two men are companions. Their closeness, the rest of one on the other, and the unforced asymmetry of attention suggest people who know each other. Perhaps they are studio models taking a break; perhaps they are friends at a threshold; perhaps the pose is an improvisation the painter saw and saved. The withholding of anecdote is powerful. It avoids exoticism or stereotype and insists on presence as sufficient. The narrative here is encounter—between the two sitters and between them and us.

Representation, Humanity, And The Dutch Seventeenth Century

The historical title reminds us that in Rembrandt’s Amsterdam, people of African descent were visible yet often categorized through reductive lenses. What distinguishes this painting is precisely its refusal to generalize. Each man’s physiognomy is built from particular planes, temperatures, and tempos of touch. Rather than costume them as biblical types—something Rembrandt also did in other contexts—he allows them to remain contemporaries. That decision matters. It records, in paint, the existence and dignity of Black residents in a European city long before modern portrait photography affirmed such visibility.

Material Culture And Dress

The garments complicate time and place. The right sitter’s chest bears a suggestion of metallic patterning, and the drapery at his neck evokes classical or eastern robes. Rembrandt often hybridized costume, borrowing studio props to achieve a timeless gravity. Here the fabrics serve two ends: they provide large, quiet shapes on which light can rest, and they free the heads from the constraints of contemporary fashion. The figures become both of their moment and larger than it.

The Background As Breathable Space

Behind the figures, Rembrandt stages his familiar chamber of “brown air,” a modulated field that hovers between wall and atmosphere. It grows warmer toward the right and cooler, darker to the left. This gradient amplifies the emotional asymmetry of the heads—closed, open; dusk, ember—without declaring a hierarchy. The slight aura around the right head, where lighter scumbles surround the hairline, reads as breath more than halo. The space is forgiving; it keeps the encounter private and undramatic, the visual counterpart of a room where conversation can take place.

Psychology In Half-Tones

What makes the painting so persuasive is its reliance on half-tones. Rembrandt does not draw sharp lines around features; he lets values negotiate. In the right sitter’s face, for example, a cool gray under the eyelid supports a warmer beige on the cheek; the nose bridge brightens but never isolates; the lips are delineated by temperature shift rather than outline. The left sitter’s features are built from even subtler steps, so that his inwardness arises from the paint itself. This method has ethical as well as aesthetic force. It resists caricature and acknowledges complexity—an important corrective in a world quick to stereotype.

A Late-Style Ethic: Presence Over Performance

Across Rembrandt’s late work, authority resides in steadiness, not display. “Two Negroes” exemplifies this ethic. The picture has no emblematic props, no allegorical flourish. Its uprightness comes from looking well and caring for what one sees. The men are neither idealized nor instrumentalized; they are allowed to command the space simply by being there. This is Rembrandt’s radicalism: painting as a form of witness.

Technique And Pentimenti: Decisions In The Open

Evidence of revision—pentimenti—gives the picture life. Along the right jaw, a softened restatement suggests he adjusted the head’s angle to catch light more humanely. At the left shoulder a dark mass beneath the surface indicates an earlier, bulkier contour scraped down to make room for the companion. Highlights on the right drapery feel like late additions—firm, bright strokes that stitch chest to face. Such visible decisions read as honesty. The painting shows its thinking.

The Viewer’s Role And Distance

We stand close, at conversational range, slightly below the level of the right sitter’s gaze. Because the left sitter looks down and the right looks across and past us, we are given latitude: we can attend without being interrogated. The lack of a staging device—no table edge, no window—keeps our role undetermined and therefore intimate. We are not spectators at a show; we are present in a room with two men who are present to each other.

Modern Resonance: Visibility, Care, And Art’s Capacity To Repair

Seen today, the painting carries a double resonance. It is a superb example of late Baroque portraiture—restrained palette, atmospheric space, virtuosic handling. It is also an early, unusually respectful representation of Black subjects in European art. The work does not erase the entanglements of its time; rather, it counters them by offering visibility without sensationalism. Artists and viewers continue to learn from this posture of care: look closely, lavish craft on particular faces, let light confer dignity rather than dominance.

Lessons For Makers And Viewers

For painters, the canvas is a manual on how to achieve richness with a restricted palette; how to distinguish two complexions under one light; how to orchestrate a double portrait without props; and how to let brushwork alternate between decisive and atmospheric to keep a surface alive. For viewers, the painting models a way of seeing people—notice how the eye moves from the left head’s inward arc to the right head’s outward lift; how the amber at the right shoulder ties to the moist light in the eye; how the darker lower left keeps the whole mass from floating. The more slowly one looks, the more the figures return, as people do when given time.

Why The Painting Endures

“Two Negroes” endures because it is grounded in the simplest, hardest task: to show two persons as fully human under the pressure of light and time. Nothing in the composition competes with that task. The warm air, the sober clothes, the asymmetry of postures, the modest scale—all exist to focus our attention on living faces. Rembrandt’s late certainty—that presence itself is meaningful—finds one of its most eloquent expressions here.

Conclusion: A Shared Light

In 1661 Rembrandt gathered earth pigments and a merciful beam to portray two Black men with the same seriousness he gave to princes and apostles. One leans and listens; the other lifts and meets the room. Their bodies share space and light without strain. The painting asks for a similar generosity from us: to grant time, to let light fall where it will, and to meet the gaze it offers with the regard it deserves.