Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

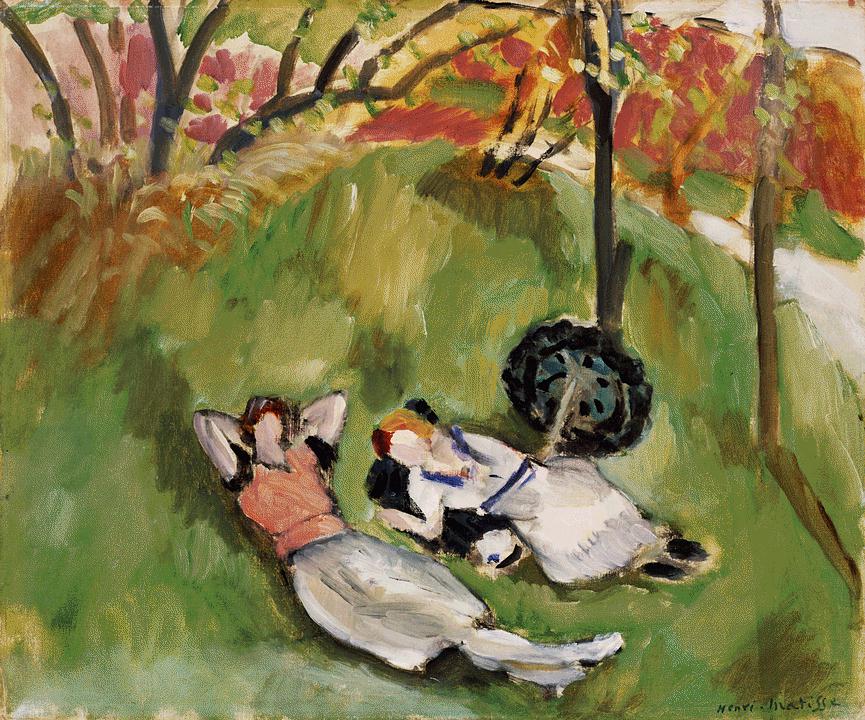

Henri Matisse’s “Two Figures Reclining in a Landscape” is a study in how repose can animate a field of color. Two women rest on a sloped green lawn beneath a canopy of lightly sketched trees. One, in a coral top and pale skirt, lies with her hands tucked behind her head; the other, in a white dress trimmed with blue, has folded herself into a soft diagonal beside a dark wheel-like shrub. Behind them, autumnal oranges and reds flare between tree trunks, and a bright path lifts along the right edge. With a handful of tuned hues—spring greens, coral, blue, umber, and ember-like reds—Matisse composes a countryside that feels both immediate and musical. The canvas belongs to his Nice-period pursuit of calm, but it retains the buoyant freedom of earlier Fauvist experiments: color remains the subject, and nature is an instrument on which he plays a clear chord of leisure.

A Sloped Meadow Turned Into a Stage

The first sensation on meeting this picture is tilt. The lawn runs upward from lower left to upper right, turning the ground into a kind of stage where bodies can read at a glance. Matisse exploits that tilt to slow the eye: we slide from the bright path at far right down into darker greens, settle on the reclining figures, then drift toward the warm leaves that ring the top edge. There is no hard horizon calling us outward; the composition invites us to stay with the grass, to inhabit surface rather than chase distance. This is characteristic of Matisse’s modern classicism. He keeps depth close to the canvas, making space a matter of layered planes and overlapping rhythms rather than linear perspective.

Composition Built From Two Diagonals and Three Posts

The design rests on a small set of strong directions. The women form two diagonals that echo the pitch of the hill, their bodies like gentle lightning bolts laid across the turf. Three verticals—slender tree trunks—interrupt those diagonals and keep the field from sliding. At upper left, a branching tree flares into loose, calligraphic foliage; at center-right, a trunk shares its base with a round, black-green shrub that reads like a dark cymbal; at far right, a narrower trunk borders the pale path. The eye moves in a figure-eigth: down the hill with the coral-shirted figure, across to the white-dressed companion, up the central trunk to the orange canopy, and back down the right-hand path. The arrangement is casual only in appearance; every weight has its counterweight.

Color Climate: Greens That Breathe, Reds That Glow

Matisse’s greens carry the painting’s weather. They are never a flat “grass” color, but a spectrum—from lemony strokes where light glances off new blades, through sap-green midtones, into moss and olive where shade thickens. Loose, transparent washes let the ground show through, so the lawn feels aerated. Against this living field, the foliage at the top of the picture lifts into autumn heat: oranges edged with rose and umber ignite between branches like embers in a grate. These reds never overwhelm, because they are contained within the upper band and parceled out in broken strokes. The palette’s cool anchor sits in the companion’s blue-trimmed dress, which tempers the greens and speaks to a nearby sky we cannot see. Black, sparingly used in outlines and the shrub-ring, acts as a stabilizer rather than a heavy note.

Brushwork as Evidence of Breathing

The surface preserves the rhythm of the artist’s decisions. Grass is made with quick, elastic pulls of the brush that change speed as they move across the slope; small pauses leave dry edges that feel like sun on brittle blades. Tree trunks are drawn with loaded, calligraphic strokes that thicken and thin like handwriting, giving them organic authority. The warm canopy is dabbed and dragged, allowing colors to mix on the canvas so that no leaf is counted but the mass is convincing. The figures are modeled with a few confident planes—coral and grey for one, white and blue for the other—then locked in by a dark elastic contour. Matisse stops as soon as each passage “reads,” protecting freshness and the sense that air circulates.

The Two Figures as Measures of Ease

The pair of women provide two registers of rest. The coral-shirted figure leans into the hill with hands clasped behind her head, the universal sign of unselfconscious ease. Her attitude establishes the picture’s tempo: long, steady, unhurried. The companion in the white dress folds into a smaller diagonal. A blue sash cinches the waist, and the dark trim of her bodice gathers attention around the face. She props herself on one elbow, the other hand relaxed across her lap. Together, the bodies read as variations on a theme of leisure—one stretched, one nested—mirroring the lawn’s long sweeps and the shrub’s compact circle.

Drawing That Conducts Rather Than Cages

The dark contour that runs around limbs, dresses, and tree trunks is not a prison; it is a conductor. It tightens at elbows, knees, and the crisp edge of the blue sash, then loosens across cheeks and hips where light should pass. Around the wheel-like shrub it thickens into a toothy ring, clarifying a dense texture with minimal means. This living line keeps the painting musical: it sets tempo, indicates entrances, and coordinates the ensemble of parts without reducing them to outlines.

The Round Shrub as Pivot

Near the meeting of figures and tree trunk sits a dark, scalloped ring—the shrub that at first looks like a wheel. It is a pivot point that performs three tasks at once. It anchors the central vertical trunk to the ground; it interrupts the long diagonals with a compact, rhythmic circle; and it provides the palette’s deepest value, making nearby skin tones and light grass pop. Without it, the lower half of the painting would feel soft and drifting; with it, the field gains a firm hinge.

Pattern as Timekeeper

Like many Nice-period works, this canvas uses pattern sparingly but decisively to keep time. There is the implicit pattern of grass strokes marching up the slope; the scalloped repeats in the shrub; the broken flecks in the orange canopy; and the discreet piping of blue along the white dress. These repetitions do not decorate; they regulate the eye’s pace. As the gaze travels from one repeat to the next, it experiences a gentle metrical beat, like walking across the hill in time with a friend’s breathing.

Light Distributed Through Relations

The painting’s light is everywhere and nowhere. There is no spotlight, only a network of relationships. Greens brighten where they open to the sky and darken under trees and figures; reds ignite where branches thin; the path at right turns paler where it ascends; sleeves and skirts catch cool reflections from the lawn. Highlights are small and precise—the white dress flashes along a pleat; a narrow glint runs across the coral shoulder; a band of lighter green grazes the hill crest. Because illumination arises from how colors sit beside each other, the scene reads as an atmosphere rather than an arrangement of lamps.

Space Held Close to the Surface

Depth comes from overlap—figures over grass, trunks over foliage, canopy over sky—and from value steps, not from a plotted vanishing point. The sloped lawn fills most of the field, keeping us close to the ground; the path at right is a pale wedge that hints at distance without dragging us away. The effect is intimacy: we are not observers from a vista; we are nearly on the grass with the women, close enough to hear wind in leaves and the small sounds of fabric moving.

A Landscape of Sensation, Not Description

Matisse is not interested in botanical detail. The species of tree is unspecified; blades of grass are not counted; faces are generalized. He trades description for sensation. The tangible truths—cool turf under the shoulder, late-summer warmth in the leaves, the way a hill changes the angle of rest—arrive through tuned color intervals and the pressure of edges. The viewer recognizes the day because the relationships are right, not because the facts are listed.

Dialogue with Earlier Fauvism and the Nice Calm

This picture keeps a foot in two Matisse worlds. Its broken color, embers of orange, and declarative line remember Fauvism’s conviction that color could carry structure. But the total effect is calmer, the palette measured, the drawing considerate; it belongs equally to the Nice interiors and gardens in which the artist sought a modern classicism of poise. Here, the wildness of color has been harnessed to the ethics of comfort. Leisure is not spectacle; it is a way of arranging the world so attention can breathe.

The Viewer’s Circuit and the Painting’s Hospitality

The composition invites a looping path for the eye that mirrors a stroll across the hill. Many viewers begin at the vivid orange canopy, descend the central trunk to the dark shrub, slide across the white figure, continue to the coral-shirted companion, and then glide down to the shadowed greens at lower left before climbing again along the bright path at right. Each lap rewards with small surprises: a stray saffron stroke at the edge of a leaf, a cool blue echo in a shadow, a quick notch of black defining an ear, a transparent wash where grass and dress meet. The painting is built for revisits; its hospitality increases with time.

The Ethics of Ease

In the early 1920s Matisse often articulated an ideal for art: to offer restfulness without dullness, to be a “good armchair” for the spirit. On this hillside, that ethic takes pastoral form. Nothing labors. Color bears weight quietly; contour guides without scolding; pattern keeps time. The women are neither allegory nor pinups; they are citizens of a well-tempered day. The picture honors leisure as a humane achievement—an arrangement of relations that allows mind and body to exhale.

Why the Image Endures

This canvas lingers because its order feels inevitable once seen. The diagonals of the bodies rhyme with the hill; the verticals of trees stabilize; the round shrub clinches; the canopy’s fire answers the lawn’s cool; the path promises return. The brush remains candid; the palette, specific; the mood, sustained. You can carry it like a remembered afternoon when the earth seemed to tilt just enough to cradle you, and conversation dropped into long stretches of contented quiet.

Conclusion

“Two Figures Reclining in a Landscape” converts a handful of natural facts—sloped grass, a few trees, a path, two resting bodies—into a lucid harmony. Greens breathe; reds glow; a dark circle anchors; diagonals and posts keep balance. Matisse shows how color can furnish a space where attention rests and senses stay alert. The painting’s gift is a poised calm that does not empty the world but tunes it, letting the viewer feel both the softness of the hill and the softening of time.