Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

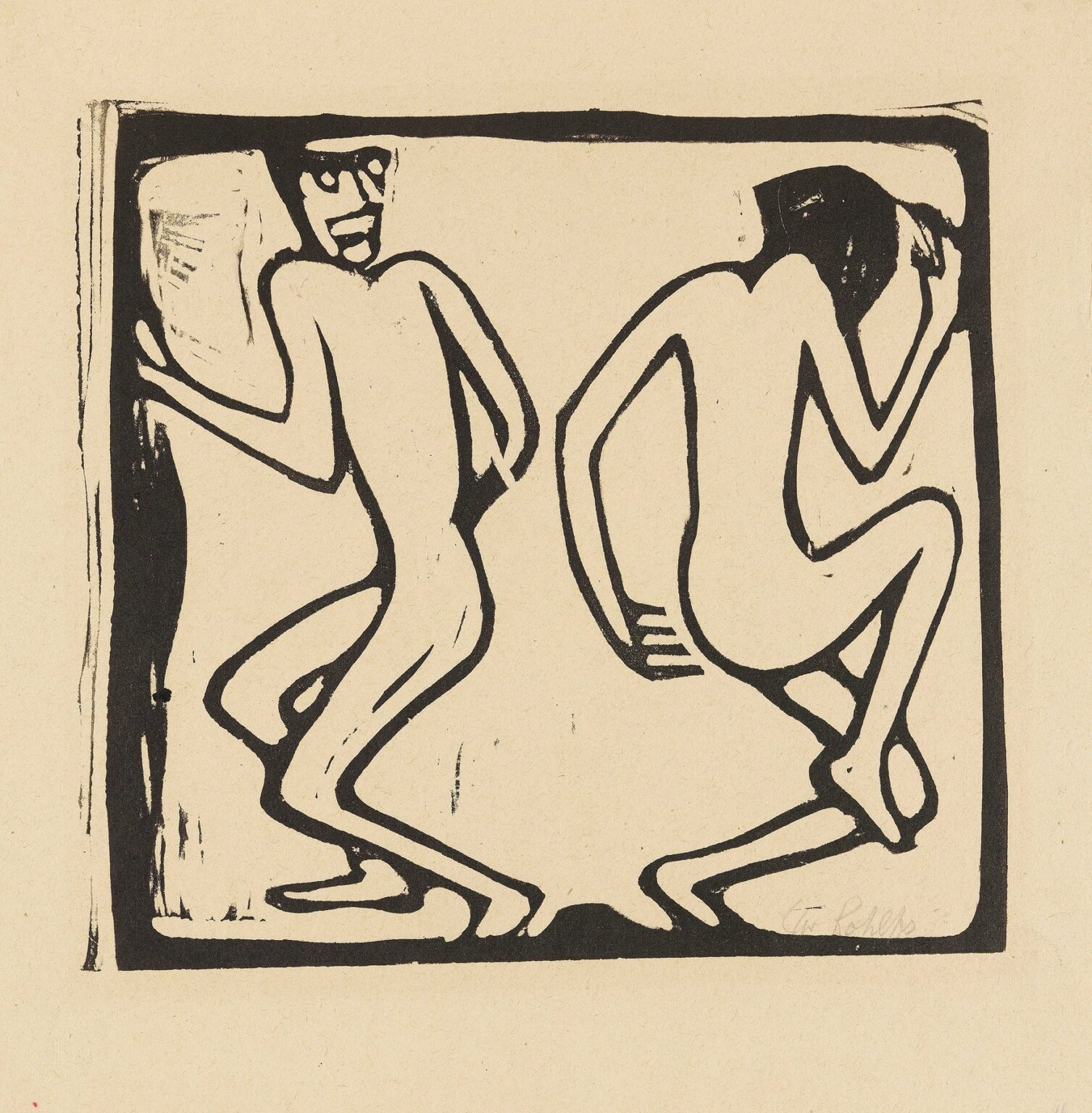

In Two dancing people (1913), Christian Rohlfs distills movement, emotion, and modern sensibility into the simplest of visual elements. Stripped of detail and color, the composition employs only bold black contours against a muted ground to evoke a scene of shared energy and rhythmic exchange. Rather than presenting a polished, static representation of dance, Rohlfs opts for an almost primitive directness that captures the very essence of human motion. Across nearly two millennia of figural depiction, artists have grappled with how to portray the body in motion; here Rohlfs finds a radical solution: pure line and gesture, unencumbered by setting or narrative, convey the dance’s emotional charge more powerfully than any anatomical precision could.

Historical Context

By 1913, Europe was a cauldron of artistic innovation. In painting and printmaking, the pioneers of Expressionism sought new ways to register subjective experience and internal tension, rejecting naturalism in favor of form and color that spoke directly to emotion. In Germany, groups such as Die Brücke and Der Blaue Reiter were challenging the art establishment, exhibiting works that prioritized spontaneity, distortion, and symbolic meaning. Although Rohlfs had begun his career within more academic circles, he embraced Expressionism’s radical spirit in the years leading up to World War I. Two dancing people emerges from this heady atmosphere—a time when artists looked to folk art, non-Western art, and even children’s drawings for inspiration in breaking free of traditional constraints.

Christian Rohlfs in 1913

Christian Rohlfs (1849–1938) had, by the early 1910s, already undergone a profound transformation. Trained at the Düsseldorf Academy, he spent his early career painting pastoral landscapes and genre scenes with a realist sensibility. A prolonged illness around the turn of the century prompted him to explore more experimental media—watercolor, pastel, and tempera on paper—emphasizing immediacy and texture. Friendships with younger avant-garde artists and exposure to French Post-Impressionists inspired him to push further toward abstraction. By 1913, Rohlfs was regarded as an elder statesman of German modernism, his late work synthesizing decades of innovation into compositions that are at once distilled and deeply expressive. His printmaking and drawing from this period, including Two dancing people, reveal his conviction that true artistic power lies in the integrity of mark-making.

Visual Description

At first glance, Two dancing people presents a simple rectilinear frame within which two elongated, stylized figures move in tandem. Both figures are rendered in a single continuous outline thicker in places where limbs overlap or joints bend, creating an almost silhouette-like effect. The figure on the left appears in profile, weight shifted onto a bent knee, one arm extended to press against an implied wall or partner. The head is turned toward the viewer, its minimal facial features—a pair of hollowed circles for eyes and a straight line for a mouth—suggesting focused intensity or perhaps a gasp of exhilaration. To the right, the second figure mirrors the first, body bent forward at the waist, head bowed as if in concentration, one arm raised above for balance. Negative space between them suggests a shared axis of motion, a visual rhythm that unites their gestures.

Composition and Spatial Dynamics

Rohlfs achieves a powerful sense of dynamism through careful arrangement of scale, angle, and line. The rectangular border around the figures both contains and energizes the scene: the dancers appear to press outward against its edges, as if movement can scarcely be contained. The left figure’s raised arm intersects the top border, while the right figure’s bent knee edges toward the lower frame, creating pressure points that emphasize physical effort. The asymmetry of their poses—a vertical line of support on one side, a diagonal tensile line on the other—generates visual tension. The viewer’s eye moves in a circular path around the composition: from the left figure’s face, down the curve of torso and leg, across the negative space to the right figure’s bent knee, up its back, and back around through the raised arm to the starting point.

Line and Form

Line is the fundamental building block of Two dancing people. Rohlfs’s contours vary subtly in thickness and texture, evidencing the artist’s hand rather than a mechanical process. In some places the ink appears dense and uniform, in others the brush has skipped or dried, leaving a rough, tactile edge that suggests the pulsing rhythm of muscle and sinew. The limbs flatten into abstract crescents and arcs, eschewing anatomical accuracy for expressive force. By omitting details like hands, feet, and torso modeling, Rohlfs invites viewers to project their own sensations of movement and energy onto the forms. The bodies become archetypes of dance rather than portraits of specific individuals.

Color and Contrast

Though monochrome, the print relies on the tension between black and the paper’s warm, neutral ground to convey mood and form. The deep black lines pop against the beige support, ensuring maximum legibility of gesture. At the same time, the absence of color focus attention entirely on the dance of form rather than chromatic distraction. The warmth of the paper lends a muted intimacy: the figures seem illuminated from within, as if the light of movement itself animates their outlines. The stark contrast between line and ground evokes the chiaroscuro of stage lighting, conjuring the atmosphere of a dimly lit studio or intimate performance space.

Technique and Medium

Two dancing people appears to be a woodcut or linocut executed in a single color of ink, though it may also be a bold pen-and-ink drawing meant to evoke printmaking’s aesthetic. The uniformity of line thickness, along with slight irregularities at the edges, suggests a relief-print method. Whichever the case, Rohlfs’s approach is direct and unembellished: he draws his figures with confident sweeps, leaving no pencil underdrawing visible beneath the ink. The choice of printmaking or ink underscores the theme of reproducibility and shared experience—dance itself is an ephemeral art form, fleeting in performance yet preserved in the matrix of the block or on the page.

Dance as Subject

Dance has long appealed to artists as a means of exploring the body in motion, from Eadweard Muybridge’s photographic studies to Degas’s pastel explorations on Parisian stages. Rohlfs’s contribution to this lineage is notable for its extreme reduction: rather than rendering a specific dance style—ballet, folk dance, or ballroom—he distills the activity to its most elemental gestures. The figures’ bent limbs, tilted heads, and sweeping curves combine to suggest energy, rhythm, and emotional communion without reference to a named dance tradition. In doing so, Rohlfs elevates dance from a representational motif to a universal symbol of human vitality and shared emotion.

Symbolism and Interpretation

Beneath the visible forms, several layers of meaning come into play. The two figures, while physically separate, mirror each other’s movements, implying a kind of unspoken dialogue or mutual support. Their poses, caught mid-stride, convey both tension and harmony—a balance between individual expression and communal rhythm. The blank space around them might represent the stage of life or the open expanse of human possibility, while the enclosing frame suggests societal or personal boundaries against which one asserts one’s individuality. In a broader sense, the print can be read as a commentary on modern existence: fractured by change and uncertainty, yet capable of moments of grace and synchrony when two people move in accord.

Relationship to Expressionism

Two dancing people exemplifies Expressionist ideals in its privileging of emotional truth over realistic depiction. Rohlfs shares with his contemporaries a willingness to deform and simplify the figure to convey inner states—here, the exhilaration and vulnerability of dance. Unlike some more violent or anguished Expressionist imagery, his subject is joyous physicality; yet the austere presentation and stark contrasts evoke the undercurrents of tension and effort inherent in any human endeavor. The print aligns with the ethos of Die Brücke, whose members often drew nude figures in dynamic poses, and with Der Blaue Reiter’s emphasis on art’s spiritual dimension.

Influence and Legacy

While Rohlfs’s paintings have received greater posthumous attention, his prints and drawings—Two dancing people among them—offer insight into his rigorous exploration of line and form. Later generations of artists, from mid-century Abstract Expressionists to contemporary performance artists, have continued to explore the intersection of visual art and dance. Rohlfs’s radical reduction of gesture into pure form prefigures Minimalist and Conceptual experiments in which the line itself becomes the subject. His work also resonates with graphic designers and illustrators drawn to the power of simplified silhouette and bold contour.

Conclusion

In Two dancing people, Christian Rohlfs achieves a synthesis of movement, emotion, and formal economy that remains striking more than a century after its creation. By paring away all unnecessary detail, he captures the very pulse of dance—its energy, its tension, its fleeting beauty—in a few decisive lines. The print stands as a testament to the expressive potential of line and gesture, and to Rohlfs’s belief that art’s greatest power lies in its ability to communicate the universal through the most elemental visual means. This work invites viewers not only to see dance but to feel it—to sense the tension in each tilted shoulder, the momentum in every bent knee, and the unspoken conversation that passes between two bodies in motion.