Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

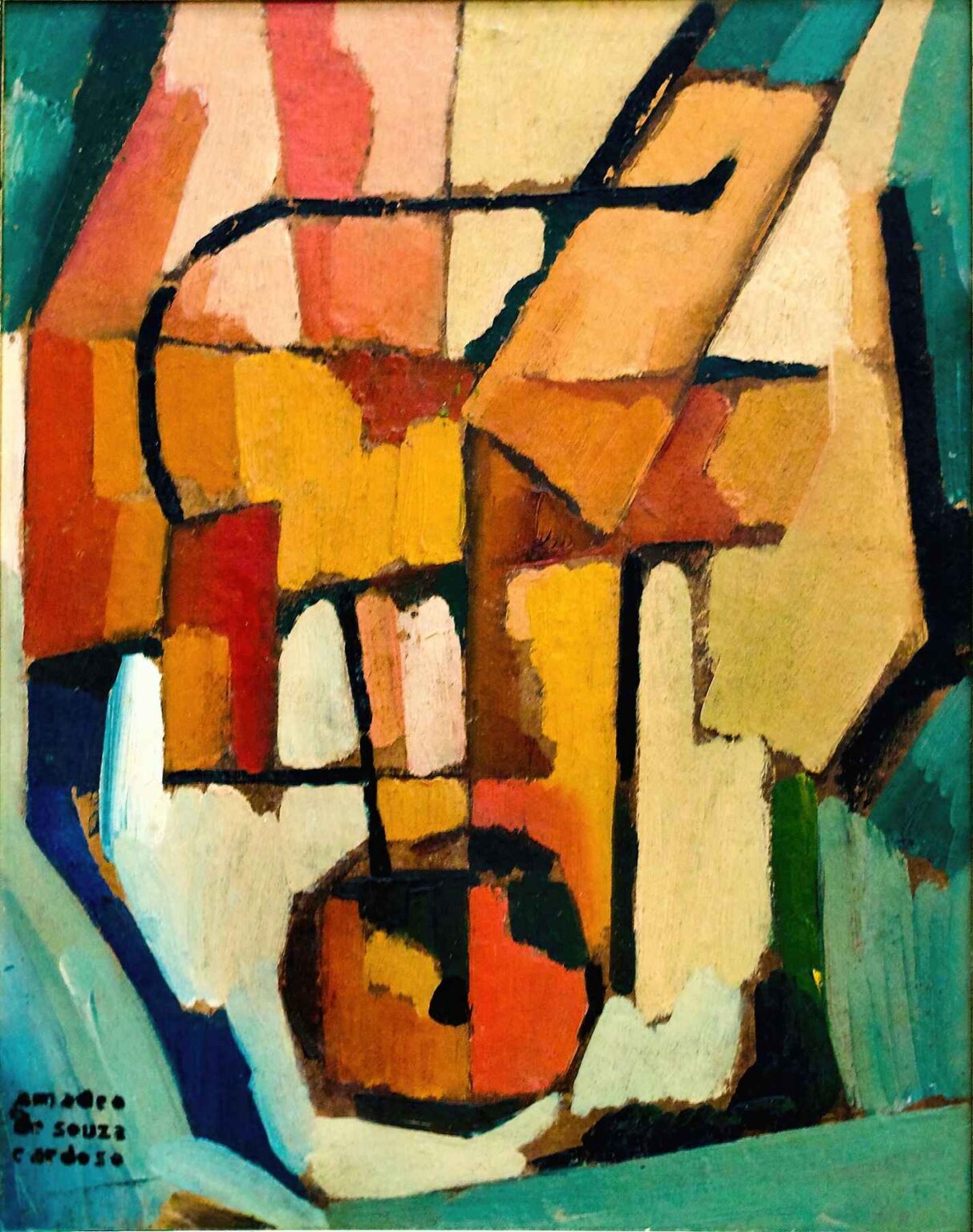

Painted ca. 1914, Tramélia by Amadeo de Souza-Cardoso stands as a landmark in early Portuguese modernism and a radiant testament to the ferment of European avant-garde on the eve of World War I. At first glance, its canvas floods the eye with fields of sunlit amber, coral, jade, and turquoise, overlaid by emphatic black lines that forge a dynamic geometry. Yet beneath this chromatic exuberance lie subtle echoes of still life—perhaps a vase or carafe, botanical fragments—refracted through Amadeo’s radical prism. Nearly a century later, Tramélia monumentally illustrates the artist’s synthesis of Cubist structure, Fauvist color, and his own Iberian decorative memory. In what follows, we will trace the painting’s genesis in its historical moment, unpack its compositional and chromatic strategies, probe its symbolic resonances, and consider the technical innovations that allow Tramélia to resonate still today.

1. Amadeo de Souza-Cardoso and His Era

1.1 Biographical Sketch and Parisian Formation

Born in Porto in 1887, Amadeo de Souza-Cardoso relocated to Paris at age 20, immersing himself in the metropolis that had become the beating heart of modern art. There he encountered Henri Matisse’s luminous Fauve works, the early Cubist experiments of Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, and the Orphic color theories of Robert and Sonia Delaunay. A close friendship with Amedeo Modigliani deepened his interest in forging a personal synthesis between drawing and color. By 1913–14, Amadeo had absorbed these currents while resolutely rejecting mere imitation—striving instead to adapt avant-garde discoveries to a Portuguese sensibility.

1.2 Return to Portugal and the Search for National Modernism

With war clouds gathering in 1914, Amadeo returned to Porto, determined to anchor his Parisian avant-garde within Portugal. His lectures, manifestos, and exhibitions catalyzed a younger generation of artists to rethink traditional academic modes. In this context, Tramélia emerges as both a culmination of his Paris-born innovations and a manifesto for a new Portuguese painting—one rooted in local craft traditions (azulejos, embroidery) yet open to the dynamism of continental abstraction.

2. Composition: Balancing Geometry and Suggestion

2.1 Architectural Framework of Planes and Lines

On a structural level, Tramélia is defined by a carefully calibrated network of intersecting planes and lines. The canvas divides into vertical bands—warm peach on the left, pale straw in the center, and aquamarine at the right—while diagonal ochre and coral wedges slice across this background. Sturdy black lines trace both gentle curves and abrupt right angles, binding these chromatic fields into an energetic lattice.

2.2 Hints of Still Life and Floral Allusion

Although largely abstract, several shapes evoke vestiges of still life. The rounded form at lower center—painted in burnt orange and deep olive—suggests the base of a vessel, perhaps a wide-bodied vase. Above it, an oblique trapezoid of honeyed yellow might recall a single flower petal caught in magnification. These fleeting references to objects never cohere into literal depiction, creating a tension between recognition and elusiveness that keeps the viewer’s eye dancing across the surface.

2.3 Rhythm and Visual Flow

Rather than a static geometric grid, the arrangement implies visual cadence. The upward sweeping arc on the left balances the downward-pointing wedge on the right, producing a subtle S-curve that leads the eye in a continuous loop. By avoiding mirror symmetry, Amadeo enlivens the composition with a sense of organic movement within a geometric framework—a hallmark of his modernist poetics.

3. Color: Mediation between Tradition and Innovation

3.1 Mediterranean Light and Iberian Hues

Amadeo’s palette for Tramélia is unapologetically Mediterranean. Golden ochres, terracotta corals, and sun-bleached creams evoke the warmth of Portuguese summers and the glow of tile-strewn patios. These are punctuated by cooler jade greens and turquoise flashes that conjure malachite and ceramic glazes found in Iberian decorative arts. In this way, the painting fuses the Fauvist emphasis on vivid, expressive color with a distinctly Portuguese chromatic memory.

3.2 Harmonies and Visual Tension

Despite its wide gamut, Tramélia remains remarkably harmonious. Each hue finds a counterpoint—a cool celadon balances a warm peach, a burnt sienna resonates against a lake-blue accent. Yet Amadeo also relishes moments of chromatic friction: a bright emerald slice abuts a creamy beige plane, generating visual electricity at the junction. It is precisely this interplay of consonance and dissonance that propels the painting’s emotional charge, inviting viewers to oscillate between pleasure in color harmony and exhilaration at bold contrast.

3.3 Surface Variation and Brushwork

Amadeo modulates his paint application to heighten the sense of depth within the flattened plane. Thick impasto passages in coral and ochre spring forward tactilely, while thin glazes in the paler fields allow the canvas weave to texture the surface. Some sections display brisk, visible brushstrokes; elsewhere Amadeo achieves a remarkably smooth, enamel-like finish. This juxtaposition of painterly gesture and flat color aligns Tramélia with Cubist and Orphist experiments yet retains a personal quality that feels less mechanical and more sensuously alive.

4. Themes and Symbolic Underpinnings

4.1 The Ephemeral Still Life as Metaphor

By abstracting a still life—vase and flower—into elemental planes and lines, Amadeo emphasizes the transitory nature of all forms. Just as cut flowers wilt and vessels can shatter, the painting’s motifs dissolve into pure geometry, reminding viewers that representation is always provisional. In Tramélia, the object is both present and absent—ghosted in color blocks that hover on the edge of recognition.

4.2 Cultural Synthesis and National Identity

In blending avant-garde formal strategies with Iberian decorative echoes, Amadeo stakes a claim for Portuguese modernism. He demonstrates that Portugal need not passively absorb Parisian trends but can instead synthesize them with its own artisanal heritage—azulejos, filigree, festival banners—into something novel. Tramélia thus becomes a visual manifesto: a call to reimagine local identity in the age of cosmopolitan abstraction.

4.3 Energy and Restraint

Within its explosive color and geometry, Tramélia contains zones of calm. The broad vertical straw-colored band at center, for instance, functions as a meditative pause amid the painting’s kinetic diagonals. This interplay of vigorous thrust and serene counterweight suggests a philosophy of balance—an acknowledgment that creativity thrives in the tension between freedom and discipline, exuberance and repose.

5. Technique and Material Considerations

5.1 Oil on Canvas and Underpainting

Amadeo’s choice of oil paint on linen allowed for both rich pigmentation and subtle layering. Examination reveals that he likely started with a warm ochre or pinkish ground, which peeks through in thinner passages to warm the overlying hues. The black lines, executed last, were applied with a loaded brush in swift, confident strokes, underscoring their role as structural anchors rather than mere outlines.

5.2 Scale, Format, and Portability

Measuring approximately 100 × 80 cm, Tramélia is modestly scaled compared to monumental Cubist works of the period. This human-scale format invites close viewing and reflects Amadeo’s desire for flexibility—he often moved between studios in Porto and Paris and required works that could travel. The painting’s manageable dimensions also align with the intimate domestic settings where early modernists frequently exhibited.

6. Reception, Influence, and Legacy

6.1 Contemporary Reception in Portugal

When Tramélia first appeared in Porto around 1915, it provoked a mixture of admiration and bewilderment. Progressive critics acclaimed its daring combination of color and form; conservative commentators dismissed it as an unintelligible departure from “proper” representation. Yet it quickly became a touchstone within Portuguese artistic circles, inspiring younger painters to embrace abstraction and experiment with color.

6.2 Resonance in European Modernism

Beyond Portugal, Amadeo’s work—Tramélia among it—found resonance with avant-garde peers. His dialogues with Cubism and Fauvism anticipated the Orphic movement and foreshadowed later explorations by artists like Sonia Delaunay, who similarly translated everyday objects into rhythmic color fields. In this sense, Tramélia occupies a pivotal place in European modernism’s evolution, bridging the analytical geometry of Cubism with the lyrical colorism of abstraction.

6.3 20th-Century and Contemporary Reappraisal

After Amadeo’s untimely death in 1918, his reputation waned amid the rise of new modernist schools. Only later, through mid-century retrospectives and scholarly rediscovery, did Tramélia and its companion works reemerge as foundational to Portuguese and European modern art. Today, Tramélia’s vibrancy and synthesis of local tradition with international currents speak powerfully to contemporary concerns about cultural identity and the global circulation of artistic ideas.

Conclusion

Amadeo de Souza-Cardoso’s Tramélia stands as a joyous and complex testament to the possibilities of early modernism. Through its daring composition of intersecting planes, its orchestration of Mediterranean-inflected color, and its subtle evocation of still-life motifs, the painting transcends mere abstraction to become a meditation on the ephemeral nature of form, the vitality of cultural synthesis, and the rhythmic pulse of human creativity. Painted at the threshold of global upheaval, Tramélia asserts that art endures through reinvention—finding new harmonies in the space between tradition and innovation. Over a century after its creation, it remains an illuminating beacon for all who seek to reconcile the local with the cosmopolitan, the decorative with the structural, and the eye’s delight with the mind’s inquiry.