Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

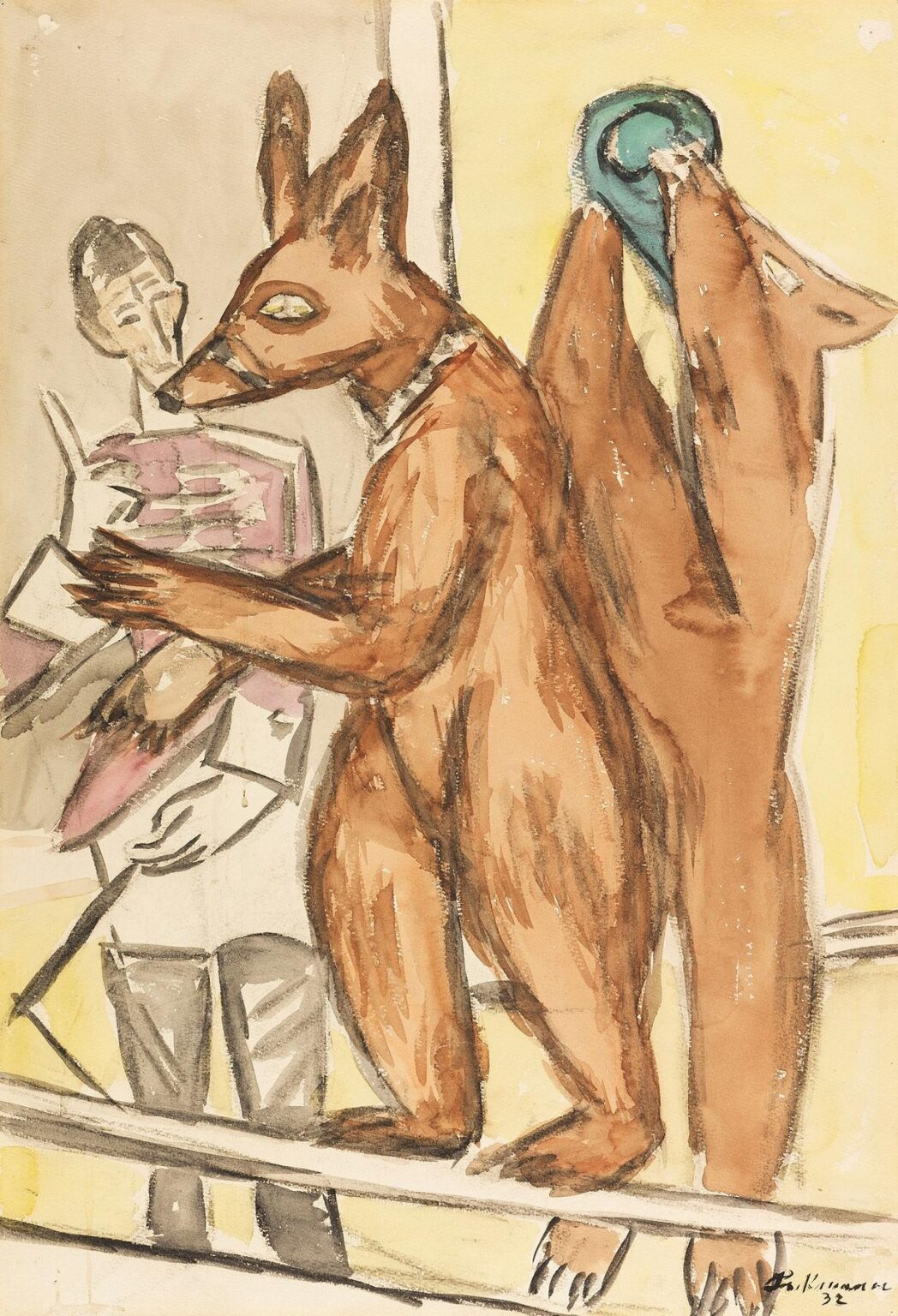

Max Beckmann’s Trained Bears (1932) is a striking oil on canvas that encapsulates the artist’s mature preoccupations with performance, identity, and the societal mechanisms of control. Painted at a time when Germany stood on the brink of seismic political upheaval, the work presents two upright brown bears, trained to mimic human gestures as they stand upon a slender platform before a faintly sketched trainer. At first glance, the scene appears deceptively simple—an animal act in a circus ring—but Beckmann’s austere palette, flattened spatial treatment, and charged symbolism reveal a far more profound meditation on the tension between freedom and constraint, authenticity and spectacle. This analysis will explore the painting’s historical circumstances, its formal construction, technical execution, thematic resonance, and its place within Beckmann’s broader artistic journey, demonstrating how Trained Bears remains a potent allegory for the human condition in the interwar era.

Historical Context

The year 1932 found the Weimar Republic teetering on collapse. Economic devastation from the Great Depression, political polarization between left and right, and the rise of extremist movements created an atmosphere of uncertainty and fear. Cinema, theater, and circus performances served as popular diversions, offering audiences temporary escapism. Yet these public spectacles also mirrored deeper anxieties: the fear of mass manipulation, the allure of charismatic authority, and the ambivalent relationship between the individual and collective. Beckmann, himself under mounting pressure—dismissed from his teaching post in 1933 and denounced by Nazi propaganda as “degenerate”—captured this fraught moment in Trained Bears. By focusing on an animal act, Beckmann invokes the precarious position of all performers—human or otherwise—under the gaze of an often indifferent or controlling public.

Beckmann’s Artistic Evolution to 1932

Max Beckmann’s career can be segmented into distinct phases: the decorative Jugendstil influences of his early work; the vigorous Expressionism of the prewar and wartime period; the austere, introspective etchings of the Gesichter series; and the disciplined yet emotionally potent figurative paintings of the 1920s and early 1930s. By 1932, Beckmann had synthesized his Expressionist roots with a robust structural clarity, a fusion sometimes associated with New Objectivity (Neue Sachlichkeit), though his art consistently transcended any single movement. Trained Bears exemplifies this mature style: the figures are rendered with deliberate flatness, outlined in emphatic brushstrokes, and situated in a stripped‑down space that emphasizes their symbolic potency over narrative detail. The painting’s theatrical staging and psychological intensity represent the culmination of Beckmann’s ongoing exploration of performance as both subject and metaphor.

Visual Description

In Trained Bears, two large bears stand upright on a raised platform or narrow beam that stretches across the lower third of the canvas. The bear in the foreground faces three‑quarter left, its almond‑shaped eye fixed on an unseen audience, ears perked in alertness. Its front paw extends slightly forward, palm out—as if offering a greeting or seeking approval. The second bear stands directly behind, its profile partly obscured, head raised to sniff the air or await a cue. Both bodies are painted in warm brown tones, with subtle highlights that articulate musculature and fur texture. Behind them, on the left, a spindly human figure—in gray tones only lightly articulated—stands clutching a ledger or book, his face drawn with minimal lines. The background divides vertically into a neutral gray plane on the left and a pale yellow wash on the right, suggesting curtained stage lighting rather than a realistic environment. The overall effect is one of staged artifice, where bears become stand‑ins for deeper human dramas.

Composition and Spatial Dynamics

Beckmann structures Trained Bears with an economy of elements that belies its psychological complexity. The horizontal platform serves as a visual anchor, bisecting the canvas and organizing the vertical thrust of the bears and the trainer. By placing the bears at center stage, overlapping yet distinct, Beckmann creates depth through figure‑to‑figure relationships rather than traditional perspective. The platform lines tilt ever so slightly, injecting a faint dynamism that prevents the scene from feeling static. The trainer, drawn with thinner, sketch‑like strokes, recedes both spatially and hierarchically; his presence is necessary for the bears’ performance but secondary to their symbolic force. The vertical division of background color further flattens spatial cues, underscoring the painting’s stage‑like quality: an ambiguous liminal space where natural laws yield to performative conventions.

Color and Light

Color in Trained Bears operates both realistically and metaphorically. The bears’ reddish‑brown fur resonates with earthy warmth, yet Beckmann tempers it with cooler shaded passages that suggest fur illuminated by artificial light. Highlights—applied in ochre and subtle ivory—trace the curves of shoulders, hindquarters, and extended paws, enhancing sculptural form. The lean gray of the trainer’s coat merges with the left background, rendering him almost ghostlike—a behind‑the‑scenes facilitator rather than a full protagonist. The right background’s pale yellow functions like a wash of stage light, casting the scene in a theatrical glow. Beckmann avoids strong chromatic contrasts, preferring muted harmonies that focus attention on form and gesture rather than decorative color.

Brushwork and Surface

Beckmann’s handling of paint in Trained Bears ranges from broad, impasto passages to delicate, linear strokes. The bears’ torsos are rendered with sweeping brushes that convey mass and weight; their fur emerges from directional lines that both model and animate the surface. In contrast, the trainer’s figure is sketched in with swift, almost calligraphic strokes—his edges bleeding into the background. Beckmann leaves traces of underpainting visible at the canvas’s edges, reinforcing a sense of immediacy and unfinished tension. The platform beam and background planes are painted with relatively thin, flat layers, allowing the canvas’s texture to show through. This interplay of thick and thin paint, dense and transparent passages, activates the surface and underscores the painting’s constructed nature.

Thematic Layer: Performance and Obedience

Central to Trained Bears is the tension between nature’s autonomy and performative obedience. Bears, as symbols of untamed wilderness, embody raw instinct; yet here they stand erect at human command, performing gestures that mimic human sociability. Their raised paw could signify both a request for reward and a salute of submission. The trainer’s ledger suggests meticulous control—a script or score dictating each movement. In 1932 Germany, this dynamic resonated with anxieties over political conformity and the manipulation of masses. Beckmann’s bears become avatars for citizens conditioned to obey authoritarian dictates, their natural vigor subsumed by choreographed spectacle. The absence of cages or collars intensifies the metaphor: control need not be visible to be effective.

The Trainer Figure: Catalyst or Oppressor?

The human trainer in Trained Bears is rendered with minimal emphasis—his coat and trousers in the same gray tones as the left background, his face sketched with a few lines. This deliberate under‑rendering positions him as an almost invisible executor of authority, operating behind the spotlight that shines on the bears. His ledger or book may contain commands, tally marks, or a performance schedule, emphasizing the bureaucratic rationalization of living beings. Yet Beckmann grants him no overt malice; his posture is neutral, his expression inscrutable. This ambiguity shifts the painting’s focus from a simple power‑over dynamic to a more unsettling suggestion that the structures governing performance are depersonalized and systemic.

Symbolism of Bears and the Stage

Throughout art history, bears have symbolized strength, ferocity, and primal instincts, from the wild to the circled ring. Beckmann’s use of bears aligns with his broader fascination with masked figures and animal‑human hybrids—exploring the boundaries of self and other. Placing them on a bare platform underscores the idea of life as performance—a stage where beings enact roles dictated by unseen authors. The painting’s vertical background division evokes stage curtains parting to reveal the spectacle, yet Beckmann omits any audience or visible ring. This absence invites viewers to question their own role: are we observers complicit in the bears’ subjugation, or might we be the unseen trainers shaping behavior through social scripts?

Psychological Dimensions

Beneath the overt allegory lies a layered psychological discourse. The front bear’s narrowed gaze and tense posture convey wariness, as if aware of the confines imposed upon it. The second bear’s raised snout suggests suspense or anticipation, hinting at moments between cues. Their proximity, almost overlapping, evokes sibling-like solidarity or mutual surveillance. The trainer’s ghostly figure introduces a human psyche split between authority and complicity. Beckmann’s flattened perspective—eschewing deep spatial recession—mirrors the flattening of inner life under performance pressure: the self becomes a surface to be read and judged, leaving little room for private interiority.

Relationship to Spectacle and Modern Life

Trained Bears can be read as Beckmann’s critique of modern spectacle—circuses, theaters, and later propaganda rallies—that reduce beings to instruments of entertainment or manipulation. In the painting, the bears perform without gratitude or agency, their gestures mechanized. The absence of decorative flourishes or elaborate set pieces emphasizes the bare mechanics of spectacle: a platform, a trainer’s instructions, and obedient bodies. In the broader context of Beckmann’s career, this interrogation of spectacle aligns with his fascination with masked figures, carnival scenes, and the grotesque—images that reveal the performative core of social rituals, from festive revelry to totalitarian parades.

Comparison with Other Beckmann Works

Beckmann revisited performance motifs throughout his oeuvre. In Carnival Play (1923), he depicts masked actors in a crowded town square; in his Gesichter etchings, he probes fragmented identities through allegorical tableaux. Trained Bears stands out for replacing human performers with animals, intensifying themes of control and dehumanization. Compared to Self‑Portrait with Horn (1938), where Beckmann places himself on stage as both musician and spectator, Trained Bears externalizes the act of performance, projecting human anxieties onto animal bodies. This displacement allows Beckmann to dramatize questions of freedom, authenticity, and complicity without reducing them to autobiographical confession.

Reception and Influence

Upon its creation, Trained Bears elicited admiration in avant‑garde circles for its formal courage and incisive allegory. Conservative critics, however, derided Beckmann’s work as overly pessimistic and dissonant. After the Nazis condemned his art as “degenerate,” Beckmann fled Germany in 1937, gaining recognition in the United States for his role as a pioneer of modern European art. Scholars have since highlighted Trained Bears as a prophetic commentary on authoritarian spectacle, influencing later artists concerned with performative identity—such as Francis Bacon’s existential dramas and Alberto Giacometti’s attenuated figures. The painting’s enduring power lies in its uncanny ability to fuse animal instinct, human performance, and systemic control into a singular, haunting image.

Conclusion

Max Beckmann’s Trained Bears transcends its immediate subject—a circus act of bears standing upright—to become a profound allegory of performance, control, and the human condition. Through a disciplined composition of flattened space, restrained yet charged coloration, and assertive brushwork, Beckmann invites viewers to confront the tension between authenticity and conformity. The bears’ anthropomorphic gestures, the ghostly trainer’s ledger, and the stark stage‑like setting coalesce into a meditation on how systems of power shape behavior—animal and human alike. As both historical document of a fractious era and timeless exploration of spectacle and obedience, Trained Bears affirms Beckmann’s status as one of the twentieth century’s most incisive interpreters of modern life.