Image source: wikiart.org

First Impressions

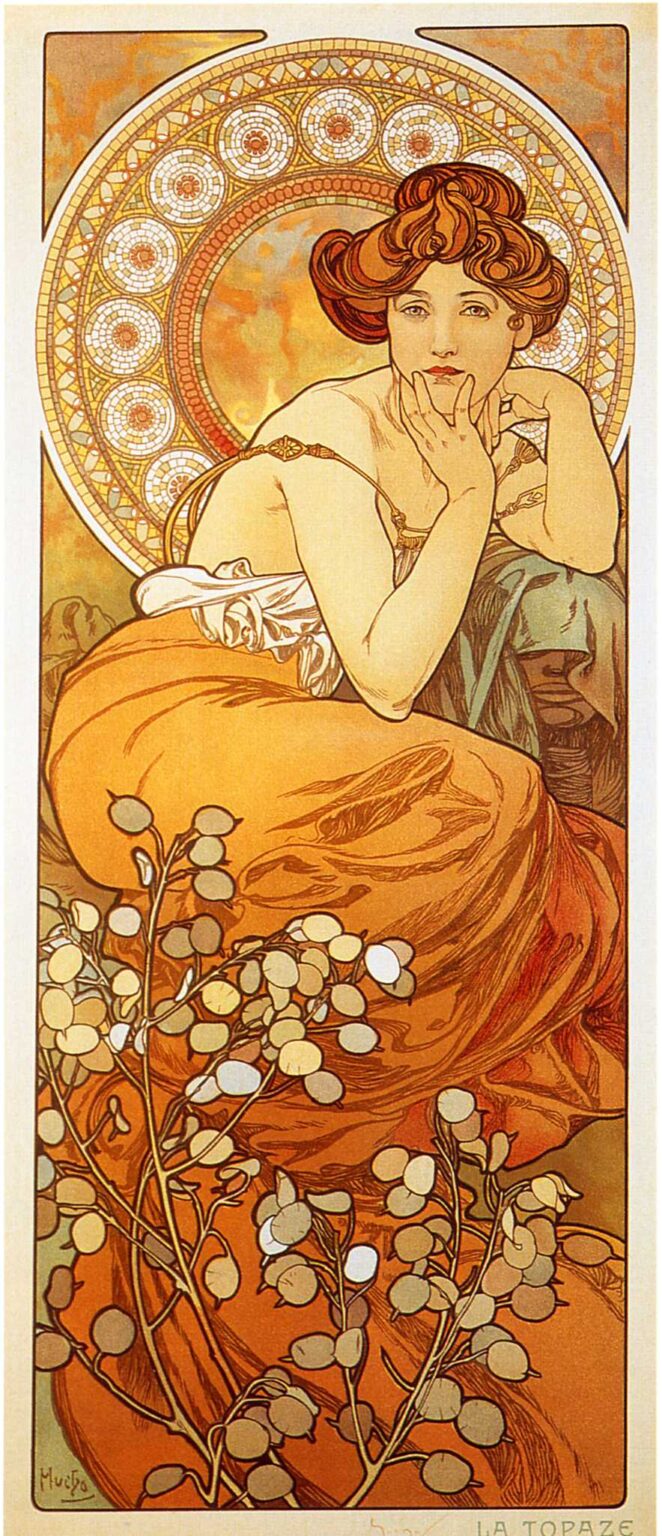

“Topaz” (1900) radiates with the mellow heat of late afternoon. A contemplative woman coils in a graceful seated pose, one hand supporting her cheek while the other tucks behind her head. She is framed by a circular, mosaic-like halo and wrapped in a cascade of amber drapery whose folds ripple like sunlit silk. In the foreground, stems of paper-thin seed pods crisscross the panel, their translucent disks catching light like little coins. The palette moves through honey, caramel, apricot, and burnished gold, a chromatic chorus that translates the gemstone’s warmth into mood.

Historical Moment

At the turn of the twentieth century, Alphonse Mucha perfected the tall decorative panel as a form that could live in modern interiors. His lithographs distilled allegories—seasons, arts, hours, and precious stones—into poised personifications that were at once contemporary and timeless. “Topaz” belongs to his gemstone series of 1900, a moment when he was synthesizing his poster mastery with a more meditative decorative ambition. The result is not an advertisement but an atmosphere: a room-sized jewel.

Place Within The Gemstone Series

Each work in the series interprets a stone through gesture, flora, and color. “Amethyst” breathes violet serenity and “Emerald” rests in verdant composure; “Topaz” turns toward mental brightness and steady warmth. Rather than painting faceted crystals, Mucha embodies the stone’s temperament—clarity without glare, heat without haste—through a woman who looks inward even as she occupies a highly patterned world.

Composition And Framing

The panel is a narrow vertical rectangle disciplined by a circular halo behind the sitter. The circle’s precise architecture stabilizes the relaxed pose, allowing the figure to lean without unbalancing the page. Below, a broad sweep of drapery anchors the middle register while the plant stems weave the lower field into a lively lattice. At the corners of the halo, small squared reserves quiet the transition between circle and frame, a subtle device that keeps the composition lucid. The eye travels upward from the seed pods to the great, rounded mass of cloth, rests at the face, and finally settles in the patterned ring—an ascent from matter to mind.

The Halo As Mosaic Facet

Mucha’s halos are never generic disks. Here the ring is built from tiny tesserae and interlocking medallions, a micro-architecture that mimics the way light refracts within a cut stone. Pale creams, soft golds, and russet accents spin through the pattern, amplifying the panel’s topaz mood. The halo functions both as sacred echo and secular jewel: a medieval idea translated into the language of Art Nouveau.

Gesture And Psychology

The sitter’s pose is unusually introspective for Mucha. One hand props the head while the other curls near the jaw, the index finger touching the lips in a sign of thought. The shoulders open; the gaze is quiet and level, turned slightly toward us without challenge. This is not the theatrical self-display of a poster star. It is the poise of someone who has paused mid-thought, cradled by warmth. The gesture expresses what topaz has long signified in folklore: steadiness of mind, benign energy, and confidence.

Color And The Spirit Of Topaz

Color carries the theme. The panel glows with apricot and honey tones that drift into sienna and copper. The background is a marbled wash of orange and pale gold that feels like a sky lit from within. Against this field, cool notes—sage green in the skirt beneath the chair, silvery greens in the seed pods—provide relief, keeping the warmth from becoming oppressive. Mucha avoids harsh contrast in favor of close intervals, building harmony the way a composer stacks notes into a chord.

Flora And Symbolic Echo

The foreground plant is likely honesty (Lunaria), whose translucent coins glide along branching stems. Their disk-like forms echo the halo, and their pale skins catch highlights like tiny cabochons. Honesty has associations with truth and the passing of time; its papery membranes suggest fragility held within strength. In a topaz context the plant reads as clarity made visible—truths illuminated but not shouted. The stems’ lively diagonals also animate the lower third, preventing the heavy drapery from feeling static.

Line, Contour, And Ornamental Intelligence

Mucha’s line is decisive and elastic. A dark contour encloses the figure and the large drapery masses; within, lighter interior lines articulate folds, hair, and jewelry. The celebrated whiplash curve flows through the sitter’s coiffure, the sweep of fabric, and the seed-pod stems, but never loses discipline. Line in “Topaz” is structure before flourish, a grammar that keeps ornament readable and mood coherent.

Drapery And Material Presence

The dress is a study in weight and sheen. Broad planes of color form the main folds; slim bands of darker tone and a few highlighted ridges suggest satin catching light. The drapery’s great rounded volume acts like a pedestal for the upper body and a visual counterweight to the intricate halo. Mucha’s economy is striking: the cloth looks luxurious without dozens of fussy details because each fold is engineered as a clear, confident shape.

Light And Atmosphere

Illumination is everywhere and nowhere. There is no single beam or dramatic shadow; instead, the panel glows as if the paper itself were warm. The marbled background supplies the sensation of radiance behind the halo, while small highlights on the shoulders, bracelet, and folds provide tactile cues. This “ambient” approach to light suits the allegory. Topaz is not a flash but a presence, and the picture’s soft, pervasive brightness embodies that idea.

Space And Depth

Like most of Mucha’s lithographs, “Topaz” operates in shallow space, a choice both practical and poetic. The chair edge, the sitter, the halo, and the plant form a set of adjacent planes, each fully legible. There is enough overlap to imply near and far, but no deep perspectival corridor to wander. The panel meets the viewer frontally, as an emblem should, and invites contemplation rather than exploration.

Jewelry, Costume, And Modernity

Small jeweled clasps punctuate the straps at the shoulders, tiny constellations that repeat the halo’s roundels and the plant’s coins. The white chemise and amber skirt blend ancient drapery with modern fashion, a hallmark of Mucha’s ability to fuse time periods into a single style. The coiffure—rolled, coiled, and lifted—provides the same synthesis: classic in contour, contemporary in finish. These cues root the allegory in the present without tethering it to trend.

Lithographic Craft

The velvety surface and crystalline edges testify to color lithography executed with care. Each hue is printed from its own stone or plate, precisely registered so contours meet and small patterns remain sharp. Gradations are achieved by thin, transparent passes rather than brush modeling. The technique allows the halo’s tiny tesserae to stay crisp and the large drapery shapes to lie calm and even, producing an object whose beauty is as much material as it is pictorial.

Rhythm And Visual Music

Mucha composes like a musician. The long legato of the skirt’s curve sets the bass line; the quick staccato of seed pods sparkles over it; the steady ostinato of the halo’s circles holds the center. The hand-to-lip gesture is the quiet pause before the cadence, and the gaze resolves the phrase. The image is not just seen; it is felt as a measured breath.

Allegory Without Anecdote

There is no narrative to decode, no myth to identify. Meaning arrives through equivalence: amber equals topaz, coin-pods equal clarity and time, halo equals inner light, thoughtful gesture equals steadied mind. This economy lets the panel travel well across eras and rooms. It is always specific in effect and general in reference, which is why it still feels fresh more than a century later.

Dialogue With Mucha’s Other Panels

Placed beside “Amethyst” and “Emerald,” “Topaz” reveals the range of a consistent grammar. All three share the circular halo, floral or botanical base, and poised female figure. Yet each claims a different psychological climate. “Topaz” sits between the cool poise of emerald and the meditative hush of amethyst, offering warmth informed by intelligence. Its marbled sky suggests air moving through light, a livelier atmosphere than the velvety calm of its companions.

The Face As Locus Of Thought

Mucha keeps the face minimally modeled: gentle transitions around eyes and mouth, a soft contour along the cheek, and a warm glow across the forehead. Set against the complexity of the halo, the simplicity reads as confidence. The index finger touching the lips is the one explicit sign, a punctuation mark for reflection. The viewer meets a mind at work, not a mask.

Why The Image Endures

“Topaz” endures because it reconciles opposites. It is ornate yet clear, warm yet composed, modern yet timeless. It demonstrates how Mucha’s Art Nouveau could be more than fashion—how it could be a philosophy of attention. In a slice of paper tuned to amber, he stages a world in which thought and beauty are the same movement of light.

Conclusion

Alphonse Mucha’s “Topaz” turns a gemstone into a human climate. Amber folds gather like sunlight; translucent pods ring like quiet bells; a mosaic halo refracts calm illumination around a thinker’s face. The lines flow, the colors breathe, and the lithographic surface wraps everything in velvet clarity. It is not a picture about a stone; it is a portrait of what the stone feels like to live with—steadfast, bright, and gently warming.