Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

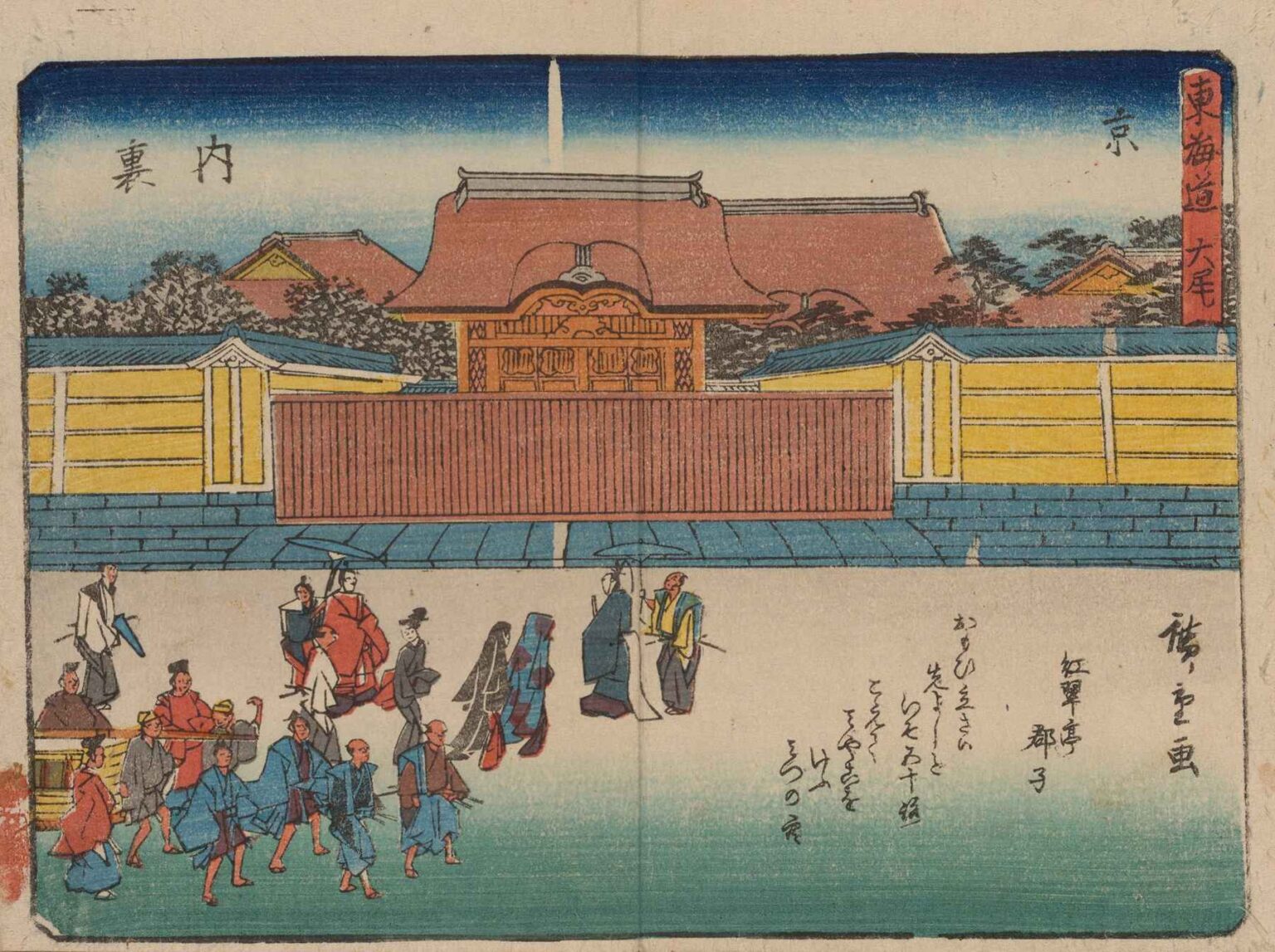

Andō Hiroshige’s Tōkaidō Gojūsan-tsugi (The Fifty-Three Stations of the Tōkaidō) is one of the most iconic and influential series in the history of Japanese ukiyo-e printmaking. Plate 56 from this series represents the final stop, Kyoto—the imperial capital of Japan. Often translated as The Fifty-Three Stations of the Tōkaidō, this work documents the journey along the famed coastal route from Edo (modern-day Tokyo) to Kyoto. Hiroshige’s portrayal of this scene masterfully captures the blend of architectural elegance, social activity, and cultural pride that defined Kyoto’s significance.

In this analysis, we will explore the historical context of the Tōkaidō road, Hiroshige’s unique compositional choices, his technique in woodblock printing, the social and political narratives embedded in this plate, and the print’s enduring legacy within both Japanese art and global visual culture.

The Artist: Andō Hiroshige and the Ukiyo-e Tradition

Andō Hiroshige (1797–1858) was a master of the ukiyo-e style, a genre of Japanese art that flourished between the 17th and 19th centuries. Ukiyo-e, meaning “pictures of the floating world,” focused on scenes from daily life, landscapes, kabuki actors, courtesans, and nature. While his contemporaries such as Hokusai leaned toward dramatic representations of nature, Hiroshige distinguished himself with his poetic sensitivity, atmospheric depth, and narrative subtlety.

The Tōkaidō Gojūsan-tsugi series, produced after Hiroshige’s journey along the coastal route in 1832, is widely regarded as his magnum opus. Each plate in the series depicts a different station or stop along the route, presenting an artistic travelogue that melds realism with lyricism. Plate 56, representing Kyoto, is the final visual destination and carries a heightened sense of cultural culmination.

Historical Context of the Tōkaidō Route

The Tōkaidō was the most important of the five main routes established by the Tokugawa shogunate during the Edo period. It connected the political capital, Edo, with the imperial city of Kyoto and stretched over 500 kilometers. The road served not only as a conduit for government officials and samurai, but also merchants, pilgrims, and travelers of all kinds.

The Tōkaidō road became a symbol of both national unity and regional identity. It allowed people from distant provinces to interact with the cultural and administrative centers of Japan. Hiroshige’s depiction of this journey offered commoners a way to experience the grandeur of travel and distant places through affordable art.

By the time Hiroshige completed Plate 56, Japan was still under the isolationist sakoku policy, which made internal routes like the Tōkaidō central to both movement and imagination. His prints are thus more than scenic images—they are cultural documents.

Plate 56: Composition and Setting

The scene in Plate 56 unfolds in front of what is likely the gate of the imperial palace in Kyoto. The composition is characterized by horizontal layering. In the foreground, groups of people dressed in varied attire walk along a wide road. The middle ground features a solid red wall and yellow structures, which guide the viewer’s eye toward the ornate gate and temple roof beyond. In the background, stylized trees and sloping rooftops suggest a deeper space, rendered with a sense of calm and quiet elegance.

The most striking feature is the architectural prominence of the gate. With its curved gables, ornamental carving, and symmetrical presence, it acts as a visual and symbolic threshold. The gate represents Kyoto’s cultural authority, religious tradition, and imperial legacy. It is at once a literal entrance and a figurative one, marking the end of the journey from Edo.

Hiroshige’s meticulous attention to architectural detail and spatial order is balanced by the informality and animation of the figures below, who add rhythm and narrative to the scene.

Depiction of Figures and Social Dynamics

Unlike many landscape prints that focus on nature or topography, Plate 56 gives considerable weight to human activity. The foreground teems with various individuals—pilgrims, samurai, travelers, and entertainers. Their clothing, postures, and interactions reflect the diversity of travelers on the Tōkaidō.

Several figures wear traveling gear: straw hats, sandals, and carrying poles. One man holds a ceremonial umbrella, while others seem engaged in conversation or observation. Their presence humanizes the grandeur of the palace backdrop, reinforcing the idea that Kyoto is a living city, not just a symbol.

The diversity of people depicted in this single plate points to the democratization of travel and commerce in the late Edo period. Hiroshige’s Kyoto is not an exclusive world of elites but a shared cultural heritage open to all who complete the journey.

Use of Color and Atmospheric Effects

Hiroshige’s mastery of color is evident in Plate 56. The print features vibrant yet balanced hues: the warm reds and yellows of the architecture contrast with the cooler blues and greens of the sky and road. This juxtaposition creates a sense of harmony, typical of Japanese aesthetics.

The gradient sky, fading from deep indigo at the top to pale cream at the horizon, exemplifies the bokashi technique, where pigments are carefully blended to create atmospheric transitions. This treatment gives the sky an ethereal quality and suggests either early morning or dusk, times often associated with transition and contemplation.

The vivid colors also help distinguish different visual planes, guiding the viewer from the animated foreground to the stately background. Hiroshige’s use of color is not merely decorative—it structures the narrative and emphasizes mood.

Woodblock Printing Technique

Ukiyo-e prints like this one were the result of collaborative effort. Hiroshige designed the image, but skilled carvers and printers brought it to life. The complexity of Plate 56, with its architectural lines, detailed figures, and color gradients, demonstrates exceptional craftsmanship.

Each color required a separate block, and alignment was critical to prevent visual distortion. The fine lines in the gate’s woodwork and the clarity of the figures’ robes suggest high technical precision. The success of Plate 56 lies as much in its printing execution as in Hiroshige’s vision.

This technique allowed mass production, making art accessible to a wider audience. Prints could be sold inexpensively to middle-class customers, contributing to the popularity and cultural reach of the Tōkaidō series.

Cultural Symbolism and Imperial Kyoto

Kyoto held deep symbolic significance as Japan’s historical and cultural heart. While the Tokugawa shogunate ruled from Edo, Kyoto remained the residence of the emperor and the center of traditional court culture, art, and religion.

By concluding the Tōkaidō Gojūsan-tsugi series with such a structured, harmonious scene, Hiroshige underscores Kyoto’s role as the final spiritual and aesthetic destination. The architectural centrality in the print implies a reverence for tradition and stability.

Additionally, the ordered composition, symmetrical layout, and formal aesthetic echo Confucian ideals of order and hierarchy—values that underpinned the Tokugawa regime.

Even the red gate can be read symbolically: it stands not just as an entrance but as a demarcation between the sacred space of imperial culture and the worldly hustle of the travelers. To cross it would be to enter a higher realm, culturally and perhaps spiritually.

Narrative and Emotional Impact

There is a subtle emotional resonance in this print. Although Kyoto is presented in grandeur, there is a sense of quiet achievement among the travelers. The journey is complete. The figures walk with calm, neither hurried nor restless. The architecture, though imposing, is not menacing but protective.

This stillness creates a mood of arrival and reflection. In contrast to the earlier plates in the series, which often depicted travelers in rough weather or mountainous paths, this final plate offers resolution. It suggests the satisfaction of pilgrimage, the dignity of destination.

Hiroshige’s Plate 56 therefore functions both as a geographic endpoint and a psychological resting place—a place where the outer and inner journeys come together.

Influence on Japanese and Western Art

Hiroshige’s Tōkaidō series was not only immensely popular in Japan but also had a profound influence on Western artists, particularly during the Japonisme movement in 19th-century Europe. Painters such as Vincent van Gogh, Claude Monet, and James McNeill Whistler admired and collected Japanese prints, often drawing inspiration from their compositional daring and color harmony.

Plate 56, with its bold horizontal layering and architectural framing, likely contributed to the Western understanding of how space could be structured in new and non-linear ways. The idea of using visual rhythm to guide a viewer’s emotional experience—so evident here—became foundational to modernist experimentation in the West.

The Legacy of the Tōkaidō Series

Today, Tōkaidō Gojūsan-tsugi remains one of the most celebrated achievements in Japanese visual culture. Plate 56, though sometimes overshadowed by more dramatic scenes in the series (like those featuring rain or snow), is crucial for its thematic closure. It ties the journey together by emphasizing cultural identity, architectural pride, and the human element of travel.

In museum collections and exhibitions, Plate 56 often helps contextualize the importance of Kyoto within Japanese art and history. It is a testament not only to Hiroshige’s artistic genius but also to his deep respect for tradition and continuity.

Conclusion

“Tōkaidō Gojūsan-tsugi, Plate 56” by Andō Hiroshige is more than a scenic depiction of Kyoto—it is a visual culmination of a journey through Edo-period Japan, rich with cultural meaning, architectural beauty, and social nuance. Through careful composition, masterful printing, and a keen observational eye, Hiroshige invites us not only to see Kyoto but to experience the sense of arrival, reverence, and reflection it represents.

This plate stands as a powerful example of how landscape and architecture can speak volumes about national identity, historical transition, and the emotional resonance of travel. In Plate 56, Hiroshige doesn’t just show the end of a road—he offers a moment of poetic stillness at the intersection of past, present, and memory.