Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

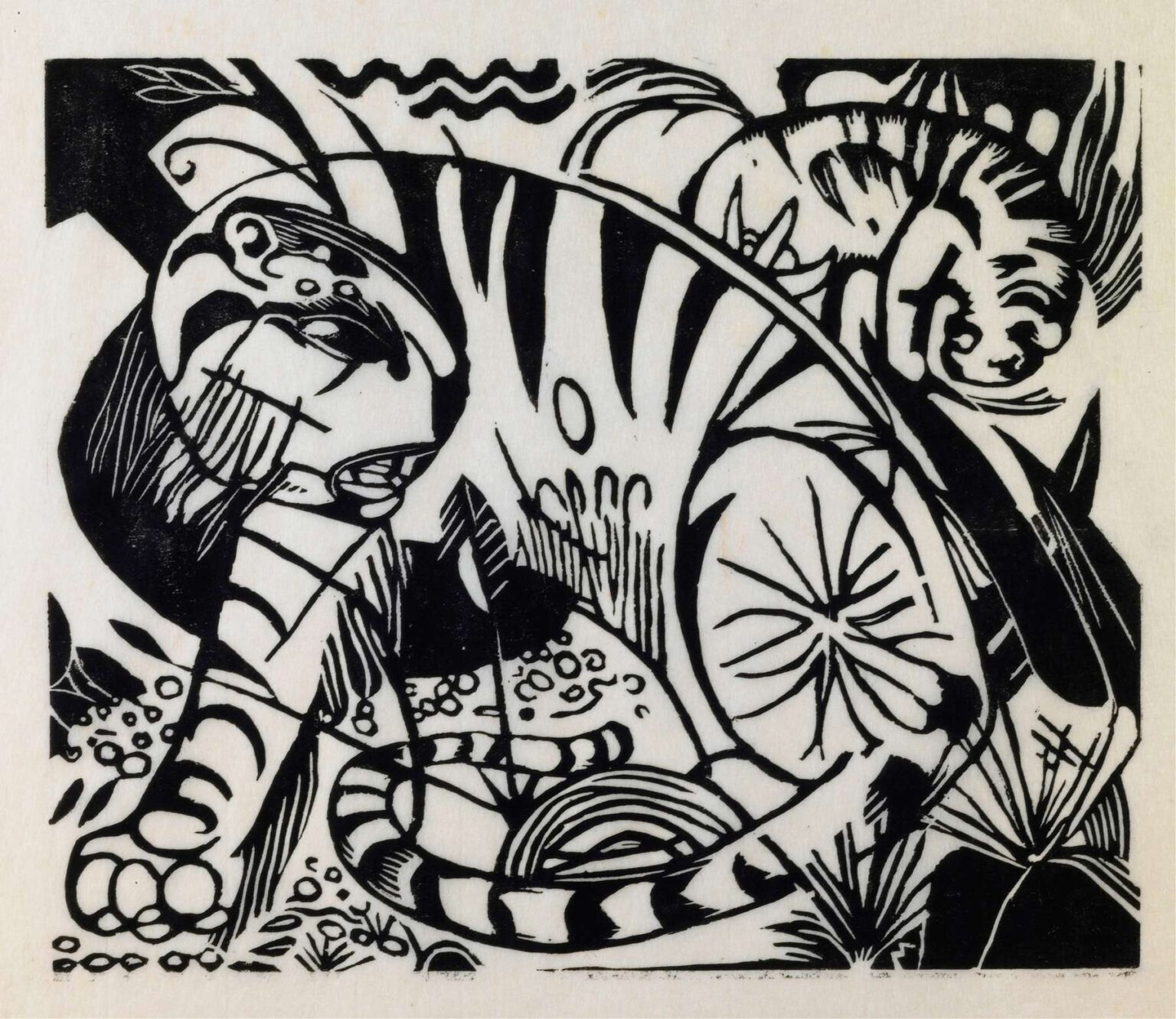

Franz Marc’s Tiger (1912) stands as a compelling fusion of animal symbolism and early Expressionist abstraction. Rendered as a black‑and‑white woodcut, the print transcends mere representation to evoke the raw energy and spiritual potency Marc attributed to the animal world. Rather than depict a tiger with photographic precision, Marc distills its essence into sweeping lines, rhythmic hatchings, and curved forms that pulse across the picture plane. The creature’s striped flanks, sinuous tail, and alert posture are suggested through dynamic contours that merge the beast with its surrounding environment. In this work, Marc transforms the tiger into an archetype of primal force, exploring themes of strength, vulnerability, and the delicate balance between predator and habitat.

Historical Context

In the years leading up to World War I, European art underwent a radical transformation as artists sought to break free from academic conventions and explore inner realities. Franz Marc co‑founded the Der Blaue Reiter group in Munich in 1911 alongside Wassily Kandinsky and August Macke. Their manifesto and almanac championed abstraction, symbolism, and the transcendental power of color and form. Marc, deeply influenced by Theosophical writings and Rudolf Steiner’s anthroposophy, viewed animals as embodiments of spiritual forces untainted by human ego. The tiger, with its fierce grace and solitary nature, became for Marc a potent symbol of vitality and the cosmic rhythms that connect all life. Created in 1912, Tiger emerged amid this ferment of spiritual and aesthetic experimentation, projecting a vision of nature’s raw energies that contrasted sharply with the mechanized brutality soon to engulf Europe.

Marc’s Evolution as a Printmaker

Although Franz Marc is best known for his luminous paintings—the Tower of Blue Horses (1913) and Fate of the Animals (1913) among them—his engagement with woodcut printmaking reveals a parallel strand of innovation. Beginning around 1912, Marc turned to relief printing for its bold contrasts and tactile immediacy. The woodcut medium required him to translate his color theories and compositional insights into pure line and silhouette. In Tiger, Marc marries the rhythmic curves of his painted forms with the stark chiaroscuro of black ink against white paper. He carved with a precision that allowed for both broad, sweeping strokes and delicate hatchings, achieving a sense of depth and movement uncommon in monochrome prints. This work exemplifies Marc’s fluid adaptation of his pictorial vocabulary to new materials, demonstrating that the emotional and spiritual force of his oil paintings could be equally potent in graphic form.

Composition and Formal Structure

The composition of Tiger unfolds within a nearly square format that heightens the sense of containment and tension. The animal’s body occupies the central field, its back forming a dominant arc from the lower right toward the upper left. The tiger’s head, slightly turned and framed by a cascade of curved lines, anchors the left margin. Its limbs extend in diagonal thrusts that contrast with the horizontal bands of its stripes, generating a visual counterpoint of motion and stability. In the background, abstracted vegetal motifs—curlicues of foliage, clustered blossoms, and wavy lines—envelop the creature without confining it entirely. This interplay of figure and environment dissolves the boundary between animal and habitat, suggesting an immersive ecosystem. Marc’s strategic cropping of the tiger’s tail and foot implies movement beyond the frame, reinforcing the sense of a powerful presence that transcends pictorial limits.

Use of Black and White Contrast

In Tiger, Marc exploits the graphic potential of black ink on white paper. The tiger’s stripes emerge as bold bands of white carved into a field of black, reversing the typical modeling of light and shadow. This inversion imbues the creature with a spectral aura, as though lit from within by its own vital energy. The densely inked areas—under the belly, within the recessed stripes, and in the background shadows—anchor the composition and provide weight. Fine hatchings articulate musculature, grass textures, and facial details, creating subtle gradations of tone within the binary scheme. Marc’s command of negative space allows white areas to breathe, balancing the print’s heavy dark masses with open luminosity. The result is a tension between visibility and concealment that mirrors the tiger’s instinctive stealth and raw power.

Line, Rhythm, and Movement

Line in Tiger functions both as structural contour and kinetic pulse. Marc carved sinuous curves to define the beast’s flanks, weaving them with sharp diagonal hatched strokes that suggest rippling muscles. The stripes, rather than being mere decorative markings, become rhythmic markers that guide the eye across the form. In the upper background, wavy lines recall flowing water or rustling leaves, reinforcing the impression of a living, breathing environment. Each carved line, whether thick and gliding or thin and staccato, contributes to an overall sense of dynamism. Marc’s use of parallel hatchings creates a vibrating optical effect, as though the tiger’s coat quivers with life. This rhythmic interplay of line weights and directions evokes the untamed energy that Marc celebrated in the animal kingdom.

Symbolism of the Tiger

For Franz Marc, animals transcended their biological identities to become symbols of universal principles. The tiger in this print embodies dualities: fierceness and elegance, solitude and immersion, danger and beauty. Marc associated red with matter and raw force, yet here, the tiger’s stripes rendered in pure black and white suggest a stripped‑down allegory of primal vitality. Positioned amidst stylized vegetation, the creature symbolizes the intricate balance between predator and prey, strength and fragility. The upward thrust of its gaze and the poised tension of its body evoke vigilance and sovereignty, reminding viewers of nature’s authority. In Marc’s larger symbolic program—where blue represented spirituality, yellow joy, and red matter—the tiger’s monochrome treatment intensifies its role as a conduit for elemental energies beyond rational control.

Spatial Dynamics and Environment

Although Tiger lacks a traditional landscape, Marc evokes spatial depth through overlapping forms and line modulation. The tiger’s body cuts across the pictorial plane, while curling grasses and abstract blooms fill the gaps, creating a rhythmic tessellation of form. The dense black background in upper corners recedes, while the white of the tiger’s stripes appears to advance. Marc’s strategic use of white space around the creature’s head and limbs suggests shafts of light filtering through foliage, even in the absence of tonal variation. This implied environment—both sheltering and revealing—immerses the animal in a world that is both real and metaphysical, reflecting Marc’s view of nature as a spiritual realm.

Emotional and Spiritual Resonance

Marc believed that art should resonate like music, tapping into emotional currents beyond conscious thought. In Tiger, the interplay of dynamic lines and stark contrasts induces a sense of awe tempered by reverence. Viewers often report a visceral reaction to the print’s vibrant energy—an encounter with something both wild and sacred. The tiger’s alert posture and intense gaze convey a readiness that transcends mere predation, suggesting a cosmic intelligence at work. This spiritual dimension is reinforced by the print’s abstraction: by dissolving literal detail, Marc invites viewers to connect with the underlying forces that animate both image and imagination. The print becomes a meditative object, a visual mantra that invites contemplation of strength, focus, and the interplay of light and shadow within the soul.

Technical Mastery and Craftsmanship

Creating a print as intricate as Tiger demanded exceptional skill. Marc selected a fine-grained woodblock to accommodate both broad strokes and delicate hatchings. He meticulously planned the design—likely through progressive proofs—ensuring that each carved line served both formal and symbolic functions. The final impressions exhibit a crispness that attests to Marc’s precise inking and careful paper selection. The slight relief embossing where the block pressed the sheet adds a tactile dimension, reminding viewers of the artwork’s materiality. Marc’s ability to balance dense black areas with luminous white shapes without resorting to gray tones underscores his mastery of the medium, demonstrating that woodcut could rival painting in emotive depth.

Comparative Perspective within Marc’s Oeuvre

Positioned among Marc’s 1912 works—such as Deer in the Forest II (1912) and Genesis II (1914)—Tiger reveals the artist’s continued fascination with the spiritual symbolism of animals. While his oil paintings often employed vivid color contrasts, his woodcuts distilled these ideas into pure form and line. Tiger shares thematic affinities with Reconciliation (1912) and Horse and Hedgehog (1913) in its exploration of animal presence amid abstracted environments. However, the tiger’s solitary majesty and the graphic starkness of this print set it apart as a study in focused intensity rather than epic drama. As a bridge between his graphic experiments and later color woodcuts, Tiger underscores Marc’s belief that abstraction—whether monochrome or polychrome—could communicate universal truths.

Viewer Engagement and Interpretive Space

Marc’s abstraction invites viewers into a co‑creative act of perception. Some may see a crouching predator poised for the kill; others may perceive the print as a symbolic emblem of inner strength or spiritual vigilance. The absence of extraneous narrative detail leaves interpretive space open: the vegetation may suggest jungle foliage or cosmic currents, the stripes may read as tally marks of experience or bursts of energy. Each viewing can reveal new connections—how a single curved line might imply muscle or motion, how a cluster of hatchings might evoke foliage or pulsating life. This open‑ended design ensures Tiger remains a living work, capable of resonating with diverse emotional landscapes and personal associations.

Legacy and Influence

Despite his brief career—cut short by his death in World War I—Franz Marc’s vision of animal symbolism and abstraction left a lasting imprint on modern art. Tiger exemplifies his pioneering integration of expressive line and spiritual allegory, influencing contemporaries such as Ernst Ludwig Kirchner and later movements including Abstract Expressionism. Marc’s conviction that art could reveal inner necessity rather than mere surface appearances resonates with today’s artists who explore ecological themes, animal rights, and the symbolic power of the nonhuman world. Tiger continues to inspire printmakers and painters alike, demonstrating the enduring potency of distilled form and the capacity of black-and-white imagery to convey profound emotional and spiritual states.

Conclusion

Franz Marc’s Tiger (1912) stands as a masterful woodcut in which form, line, and symbolism converge to evoke the primal spirit of the animal world. Through its dynamic composition, bold contrasts, and rhythmic hatchings, the print transcends naturalistic depiction to embrace archetypal forces of strength, vigilance, and interconnectedness. Marc’s technical mastery and visionary abstraction invite viewers into a meditative encounter, one that reflects both the tiger’s physical elegance and the deeper spiritual currents that animate all life. Over a century after its creation, Tiger endures as a testament to art’s capacity to bridge the visible and invisible, the earthly and the transcendent, reminding us of the latent energies that pulse within every creature.