Image source: wikiart.org

First Look: A Tall Room Filled With Quiet Conversation

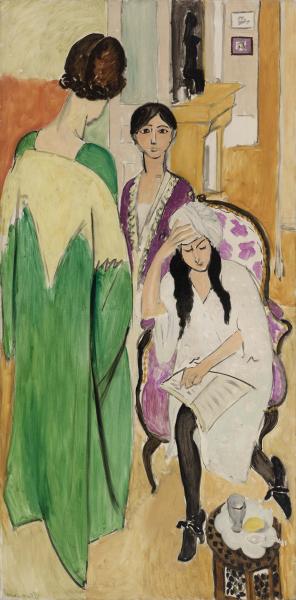

Henri Matisse’s “Three Sisters with An African Sculpture” (1917) presents a slender slice of interior life that feels both theatrical and intimate. The tall, narrow canvas stages three women in differing attitudes of attention: one stands in a sweeping green dressing gown with her back to us; another faces forward in a violet-edged robe; a third sinks into a pink-patterned chair, head tipped to one hand as if mid-thought, a sheet of paper slipping across her lap. At the far rear, above a mantel and half-framed by a doorway, a small dark figurine—an African sculpture—quietly anchors the background. Near the bottom right, a low table holds a cup, saucer, and lemon wedges. The room is pale and luminous; black contour lines keep the image crisp; color throws its weight where meaning matters. The result is a conversation among bodies, objects, and cultures, resolved into Matisse’s deceptively simple grammar of line and plane.

A 1917 Interior Shaped by Discipline and Poise

The year 1917 is pivotal in Matisse’s practice. The earlier blaze of Fauvism had given way to a measured clarity suited to wartime austerity. Black returns as a constructive color, not merely a shadow; planes flatten; details are reduced to essentials. At the same time, the painter’s fascination with textiles, domestic spaces, and non-European art—especially the expressive power he perceived in African sculpture—continued to animate his studio. This painting sits at that crossroads: a disciplined image that still luxuriates in fabrics and pose, in which a small sculptural presence folds global reference into the privacy of a Paris room.

The Vertical Format and Its Theatrical Consequences

The canvas is unusually tall and narrow, almost like a stage wing. That format forces a stacked choreography. The standing figure in green occupies the left foreground like a screen; the frontal sister in violet aligns along the central axis; the seated sister and the patterned chair fill the lower right, creating a diagonal weight that runs from top left to bottom right. Above and beyond them, the hallway, mantel, and niches rise toward the top edge, leading the eye to the African figurine. The composition reads as a vertical procession: curtain, actors, backstage. This verticality also echoes the human figure, so the viewer feels close to life-size scale even within such abbreviated space.

Color as Structure: Green, Violet, White, and Warm Ocher

Matisse builds the picture from four principal colors. The green robe is a large, low-chroma field that carries most of the compositional weight on the left; violet and rose punctuate the middle through the sitter’s robe and the upholstery’s floral sprays; whites and off-whites shape faces, hands, stockings, and the dominant garments of the seated figure; warm ochers and honeyed beiges create floor, mantel, and passages of wall that bathe the room in gentle warmth. Black contour threads everything together. Because the palette is controlled, each color works in relation to others: the green calms the heat of the ocher; the violet freshens the neutrals; the blacks carve planes and keep the whites from dissolving. Nothing is gratuitous; every hue has a job.

Drawing With Black: The Carpentry of the Picture

Matisse’s line in 1917 is elastic and authoritative. With a single black stroke he can declare the fold of a sleeve, the rim of the chair, the profile of a cheek. In this interior the contour does true structural work. The sweeping hem and spine of the green robe are held by one long, confident line. The violet robe is edged by a row of dark beads, which function simultaneously as ornament and as the seam that pins the figure to the ground plane. The seated sister’s hand on her forehead is described by a few decisive turns that read instantly across the room. Because line is so strong, modeling can remain light; color fields can be broad and restful without losing clarity.

Gesture and Personality Without Anecdote

The painting thrives on differentiated attitudes. The figure in green, turned away, acts like a mediator: she invites the viewer in but withholds her face. The central sister’s direct gaze steadies the scene; she is the picture’s vertical fulcrum. The seated sister is absorbed, her hand supporting a tilted brow as a sheet of paper slips across her lap. Are we seeing fatigue, study, or reverie? Matisse refuses anecdotal specifics, allowing mood to arise from pose and relation rather than narrative prop. Because the three figures occupy distinct roles—screen, axis, and diagonal repose—the room hums with psychological balance rather than plot.

The African Sculpture: Small, Dark, Incredibly Potent

Above the mantel, a compact, dark figure stands in profile. It is physically tiny compared with the near life-size sisters, yet it carries conceptual weight. Matisse respected African sculpture for its ability to reduce forms to essentials while preserving presence—precisely the ambition of his own wartime language. Here the figurine plays several roles at once. It anchors the distant space as a vertical counter to the green robe; its silhouette echoes the clarity of the sisters’ profiles; and it introduces a cross-cultural lineage into a domestic French interior. Rather than exoticize, Matisse positions the sculpture as a peer: another distilled image among distilled images, a companion in the pursuit of expressive economy.

Interior Architecture as Rhythm

The room’s structure is clarified by a series of softened rectangles: doorway, overmantel, wall panels, and chair back. Each rectangle arrives in a different key—warm ocher, cool white, violet pattern—so the architecture becomes rhythm rather than architectural description. The mantel’s diagonal shelf and the small framed pictures on the wall punctuate the ascent toward the figurine, coaxing the eye upward. At the bottom right, the little round tea table breaks the rectangle rhythm with a circle, adding an ornamental beat that keeps the composition from freezing into grids.

Pattern and Quiet: The Balance Matisse Seeks

Matisse loved pattern, but he uses it here sparingly and strategically. The pink chair’s floral sprays, nested inside a black contour, add a soft lyricism around the seated figure’s head. The violet robe bears a dotted trim that reads as both adornment and edge. The green robe, though mostly unadorned, contains a gentle zigzag at the shoulders that catches just enough light to keep the surface alive. Because pattern is localized, large quiet fields remain: the pale dress and stockings of the seated sister, broad swaths of wall, the plain green of the standing figure. This ratio—small areas of intricate pattern to large areas of quiet—produces the calm Matisse famously desired.

Brushwork and the Truth of the Surface

Although the drawing is firm, the paint handling is transparent and tactile. In the green robe, long strokes drift in a single direction, allowing thin spots to breathe the ground color and creating natural variations that suggest silk or lightweight wool. Flesh is handled as slips of warm and cool pinks, with minimal blending so that a cheek reads as a single decisive plane. The walls and floor are brushed with broader, softer passes that reveal canvas weave and give the room an airy, lived-in feel. Everywhere the surface remains legible: a record of choices rather than a veneer of illusion.

Asymmetry and the Art of the Slight Difference

Matisse keeps the three women from collapsing into a decorative triad by nurturing asymmetry. The green robe’s back is broad and unbroken; the violet robed figure’s face carries a small, searching asymmetry in the eyes; the seated sister’s posture opens to the right, legs angled, paper slipped askew. Even the furniture participates: the chair is slightly off-center, the tea table pushed to the corner, a delicate saucer nearly touching the picture’s edge. These tiny displacements produce liveliness without agitation, confirming that the painter’s calm is never static.

The Eye’s Journey Through the Scene

The composition conducts the gaze with ease. Most viewers enter at the green robe, its height echoing their own. From there the eye crosses the soft triangle of bare neck and hair bun to the central sister’s face. The gaze descends to the sitting figure, lingers on the bend of arm and the angled paper, then slides to the circular still life of cup and lemon at the bottom right. A diagonal lift along the chair’s rim returns the gaze to the mantel shelf, where the small dark figurine waits as a final punctuation. This circuit can repeat indefinitely because every stop offers a distinct attraction—color, contour, gesture, or object.

Everyday Objects as Tuning Forks

Matisse often inserts a simple still life to tune the surrounding color. Here the tea service on a lattice table is painted in quiet whites and grays, with the lemon offering the only concentrated yellow in the picture. That yellow hums against the ocher wall, tightening the painting’s temperature and preventing the warm ground from becoming monotone. The white porcelain echoes the sisters’ garments and knits the lower right corner to the rest of the room. Because the still life is so modest, it reads less as “tea time” than as a color chord struck softly in the ear.

The Ethics of Reduction

One of the painting’s deepest achievements is the way it does more with less. The sisters’ features are abbreviated—brows as single arcs, noses as crisp wedges, mouths as compact reds—yet the likeness of temperament is convincing. Architecture becomes measured panels; textiles are implied rather than counted; the African sculpture is a succinct silhouette. That ethic of reduction creates respect: the viewer is invited to complete what the painter starts, participating in the image rather than consuming it.

A Dialogue With the Past and With Elsewhere

Though rooted in 1917, the painting converses with long traditions. The tall format and staged grouping recall Renaissance altarpieces in reverse: secular, domestic, and horizontally unhieratic. The inclusion of the African figurine acknowledges a non-European lineage of form that had already reshaped modern art; Matisse’s treatment insists on equality rather than appropriation by placing it within his personal space as a normal element of daily seeing. And the overall calm—large planes, restrained detail—echoes Matisse’s oft-stated wish to make an art that offers repose, a wish sharpened by the anxieties of war.

The Sisters as a Scale of Attentions

Read the three figures as a scale of attention. The standing figure attends outward—she mediates the space between viewer and scene. The central figure attends to us, meeting our gaze directly. The seated figure attends inward, her hand and paper turning attention into reflection. Between these modes—outward, toward, inward—the painting proposes an economy of looking that includes the viewer. Somewhere in that triangle of attentions the small sculpture stands, silent, offering another way of seeing: from distilled form outward into the room.

What the Painting Refuses—and Gains

Matisse refuses narrative drama: no gesture breaks the room’s equilibrium, no expression tips into melodrama. He refuses rich chiaroscuro and labored modeling, opting instead for broad daylit planes and edges that declare themselves. In exchange, the painting gains modern authority. The eye rests as it travels; the mind is engaged without being crowded; the color sings quietly and continuously. The whole becomes a sustained chord in which figure, object, and space are tuned to one another.

A Bridge Toward the Nice Interiors

Soon after 1917, Matisse would build the sunlit, patterned interiors of the Nice years. This canvas forecasts that world—the love of screens, robes, fans, and bright domestic theatre—yet it still bears wartime discipline. Black contour does carpentry; color is purposeful; pattern is rationed. It is the poise before the flourish, the moment when restraint and delight were balanced perfectly.

Why “Three Sisters with An African Sculpture” Endures

The painting endures because it condenses many of Matisse’s central commitments into a single room: clarity of line, orchestration of color, respect for objects from different cultures, and a belief that art can make space for quiet attention. Every element feels necessary, nothing overworked. The three women and the small figurine do not simply occupy a room; they construct a world where differing ways of looking stand together—outward, toward, inward; European, African; decorative, essential. In that world the viewer is a welcome fourth presence, invited to stand, breathe, and look.