Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

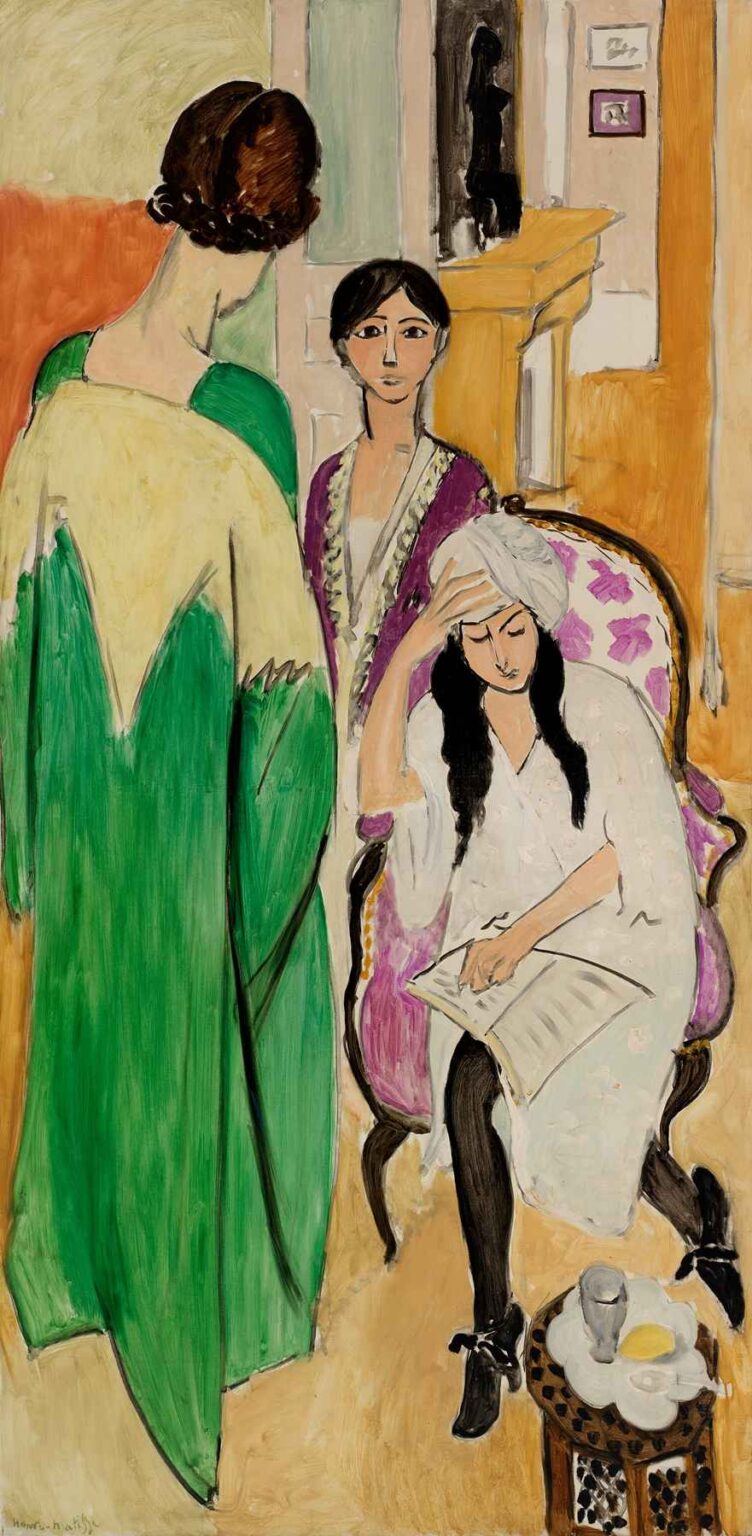

Henri Matisse’s Three Sisters with an African Sculpture (1917) brings together three female figures in a richly patterned interior punctuated by an exotic art object. Painted toward the end of World War I—when Matisse was refining his post-Fauvist style—the canvas explores the interplay of figure, décor, and cross-cultural reference. The composition centers on three women—two standing, one seated—whose elegant garments recall North African and Asian draperies, while an African statuette occupies a niche above a mantel. Through a sophisticated balance of color, flattened space, and rhythmic repetition, Matisse transforms a seemingly casual family portrait into a meditation on pattern, presence, and cultural dialogue. In the analysis that follows, we will trace the painting’s historical backdrop, dissect its compositional architecture, examine its color relationships and patterning, explore its treatment of space and surface, consider its brushwork and technique, uncover its emotional and thematic resonances, and position it within Matisse’s broader oeuvre.

Historical and Cultural Context

Painted in 1917—the penultimate year of the First World War—Three Sisters with an African Sculpture emerges from a period of deep personal and societal upheaval. Matisse had volunteered as a Red Cross orderly early in the conflict, and his wartime experiences intensified his resolve to find beauty as a counterbalance to atrocity. At the same time, Europe’s imperial reach brought African art into Parisian collections, and Matisse, like Picasso and others, drew inspiration from African sculpture’s abstracted forms and rhythmic power. Yet where Cubists often broke down form into angular facets, Matisse integrated non-Western motifs into his own decorative language, seeking harmony rather than fragmentation. The very presence of the African statuette on the mantel nods to this cross-cultural fusion: it anchors the domestic scene in a broader world of visual exchange. In the immediate aftermath of war, Matisse’s focus on interior serenity and cultural hybridity can be read as an act of creative resilience, asserting art’s capacity to unite rather than divide.

Subject Matter and Narrative

At first glance, the painting offers a domestic tableau: three young women, presumably sisters, gathered in an elegantly furnished room. The seated sister, placed centrally, reads from a small book; her downturned gaze and poised posture suggest contemplation. To her right stands a second sister, her hands softly clasped, facing directly outward with an expression of calm engagement. The third sister turns her back to the viewer—her green robe cascading in vertical folds—inviting us to enter the space and become participants in the scene. Above the fireplace, the African sculpture—a stylized female figure—overlooks the sisters, a silent witness that both connects and contrasts Western familial intimacy with ancestral, non-European traditions. While no overt narrative drama unfolds, the painting captures a moment of quiet communion: the silent dialogue between the women, their implements of reading and repose, and the emblematic sculpture that unites interior and exterior, present and past.

Compositional Architecture

Matisse arranges the figures and interior elements within a carefully orchestrated geometry. The overall format is tall and narrow, reinforcing a sense of verticality that is echoed in the sisters’ figures, the drapery folds, and the mantel’s pilasters. The seated sister occupies the center, her head approximating the vertical midpoint, while the other two frame her on either side: one facing outward, one turned away. This tripartite arrangement forms a gentle curve, guiding the viewer’s eye from the foreground to the background. The African sculpture, set directly above the seated sister’s head, creates a vertical axis that connects floor to ceiling and figure to art object. Horizontal lines—mantel shelf, book edge, floorboards—intersect this axis, stabilizing the composition. Patterned wall coverings to left and right distinguish separate zones of decoration, yet their floral and geometric motifs are calibrated to harmonize rather than compete. Through this interplay of verticals and horizontals, curves and angles, Matisse constructs a space that feels both dynamic and anchored.

Color Relationships and Pattern

Color in Three Sisters with an African Sculpture serves as both unifier and distinguisher. The palette unfolds in three principal registers: the left wall’s lavender-pink damask, the central ochre-cream panel behind the mantel, and the right wall’s warmer apricot tone. Against these backgrounds, the sisters’ garments stand out: the emerald-green robe on the left, the violet kimono-inspired coat on the standing sister, and the soft ivory dress of the seated sister. These hues—green, purple, ivory—correspond to the wall colors in a counter-harmonic dance: green against lavender, violet against ochre, ivory against apricot. The African sculpture’s deep ebony silhouette provides the darkest note in the painting, punctuating the central axis with a resonant contrast. Subtle pattern echoes—floral motifs on the left wall, abstracted blossoms on the kimono border, and the sculpture’s incised markings—reinforce a sense of visual continuity. Through these calibrated juxtapositions, Matisse achieves a chromatic embroidery that envelopes figure, object, and background alike.

Treatment of Space and Surface

While the painting portrays a coherent room, Matisse deliberately collapses depth in service of surface rhythm. The floor recedes only slightly—indicated by minimal perspective on the baseboard—and the mantel’s pilasters, though suggesting depth, flatten against the wall. Figures overlap: the green robe eclipses the seated sister’s shoulder; the standing sister overlaps the mantel; the African statuette overlaps the narrow central panel. Shadows are implied sparingly, often through darker contours rather than modeled shading. The effect is a shallow, tapestry-like picture plane where spatial recession yields to decorative unity. This flattening underscores Matisse’s departure from illusionistic depth in favor of a painting in which surface patterning and figure interplay create the primary visual drama.

Brushwork and Technique

Matisse’s handling of paint in this work balances assured fluency with considered restraint. Broad, fluid strokes define large color areas—the damask wall, the robe’s folds, the mantel’s ivory planes—while more textured, stippled marks enliven patterned zones and the sculpture’s silhouette. Flesh tones on the sisters’ faces and hands are applied in thin glazes, allowing the warmth of the underlying canvas to glow through. The kimono border and damask pattern show evidence of scumbled passages, where lifted brushstrokes allow undercolors to peek out, creating a shimmering effect. Contours—the robe’s edge, the standing sister’s profile, the sculpture’s form—are outlined in darker pigments, imparting a gentle calligraphic presence. Through this varied brushwork, Matisse maintains visible traces of his hand while preserving the painting’s overall harmony.

Emotional and Psychological Resonance

Despite its decorative surface, Three Sisters with an African Sculpture conveys a nuanced emotional atmosphere. The seated sister’s absorbed reading and the standing sister’s anchored poise suggest introspection and attentive presence, while the turned-away figure invites contemplative curiosity. Together, they embody a spectrum of engagement—from inward focus to outward watchfulness. The African statuette’s silent gaze adds another layer: it connects the living sisters to a lineage of ancestral wisdom, perhaps prompting reflection on identity, heritage, and the tensions between home and the wider world. Matisse’s calm yet richly colored environment thus becomes a setting for both familial intimacy and transcultural meditation, inviting the viewer to share in the painting’s layered psychological space.

Thematic and Symbolic Dimensions

While not overtly allegorical, the painting resonates with thematic undertones. The presence of the African sculpture highlights issues of cultural appropriation and dialogue in early twentieth-century art, yet Matisse handles it with respect, placing it in a dignified niche rather than exoticizing it. The sisters’ varied postures—reading, observing, turned away—can symbolize the different modes of looking at art itself. The integration of Western interior décor with non-Western art suggests universality of aesthetic experience, blurring boundaries between “self” and “other.” The patterns that link wall, garment, and sculpture hint at the shared impulse across cultures to find meaning through ornament and rhythm. In these subtle ways, Three Sisters with an African Sculpture becomes a reflection on art’s capacity to foster connection amid diversity.

Place in Matisse’s Oeuvre

Painted in the heart of his decorative period, Three Sisters with an African Sculpture stands alongside works such as The Music Lesson (1917) and The Dessert: Harmony in Red (1908) in its fusion of interior scene and pattern. Yet it differs in its pronounced emphasis on cross-cultural reference. While earlier interiors focused largely on fabrics and color fields, here Matisse explicitly includes an African art object, marking a deepening of his engagement with non-Western sources. The flattened spatial logic and calligraphic contours prefigure the extreme economy of form he would pursue in his late cut-outs. Thus the painting occupies a pivotal moment: fusing his decorative achievements with a new openness to global artistic traditions.

Influence and Legacy

The compositional harmony and respectful integration of African sculpture in Three Sisters with an African Sculpture influenced subsequent generations of artists exploring cross-cultural motifs. Matisse’s approach—inscribing non-Western art within a modern decorative interior—offered a model for sensitive artistic exchange rather than reductive exoticism. His flattened space and pattern-rich surfaces resonated with the Pattern and Decoration movement of the 1970s and continue to inform contemporary artists working at the intersection of figuration and ornament. The painting’s nuanced dialogue between figure, décor, and sculpture endures as a guide for how art can bridge divides through mutual respect and aesthetic integration.

Conclusion

Henri Matisse’s Three Sisters with an African Sculpture (1917) transcends the simplicity of its subject to become a richly layered exploration of color, pattern, and cultural dialogue. Through its elegant composition, harmonious palette, and flattened pictorial space, the painting celebrates both familial intimacy and the global reach of artistic inspiration. The African statuette, set among patterned walls and sisters in decorative drapery, stands as a testament to Matisse’s belief in art’s power to unite disparate traditions into a cohesive and healing vision. Over a century later, Three Sisters with an African Sculpture remains a luminous example of modern art’s capacity to weave cultural reverence, formal innovation, and emotional depth into a single, harmonious tapestry.