Image source: wikiart.org

First Look: A Compact Drama Of Calm, Color, And Kinship

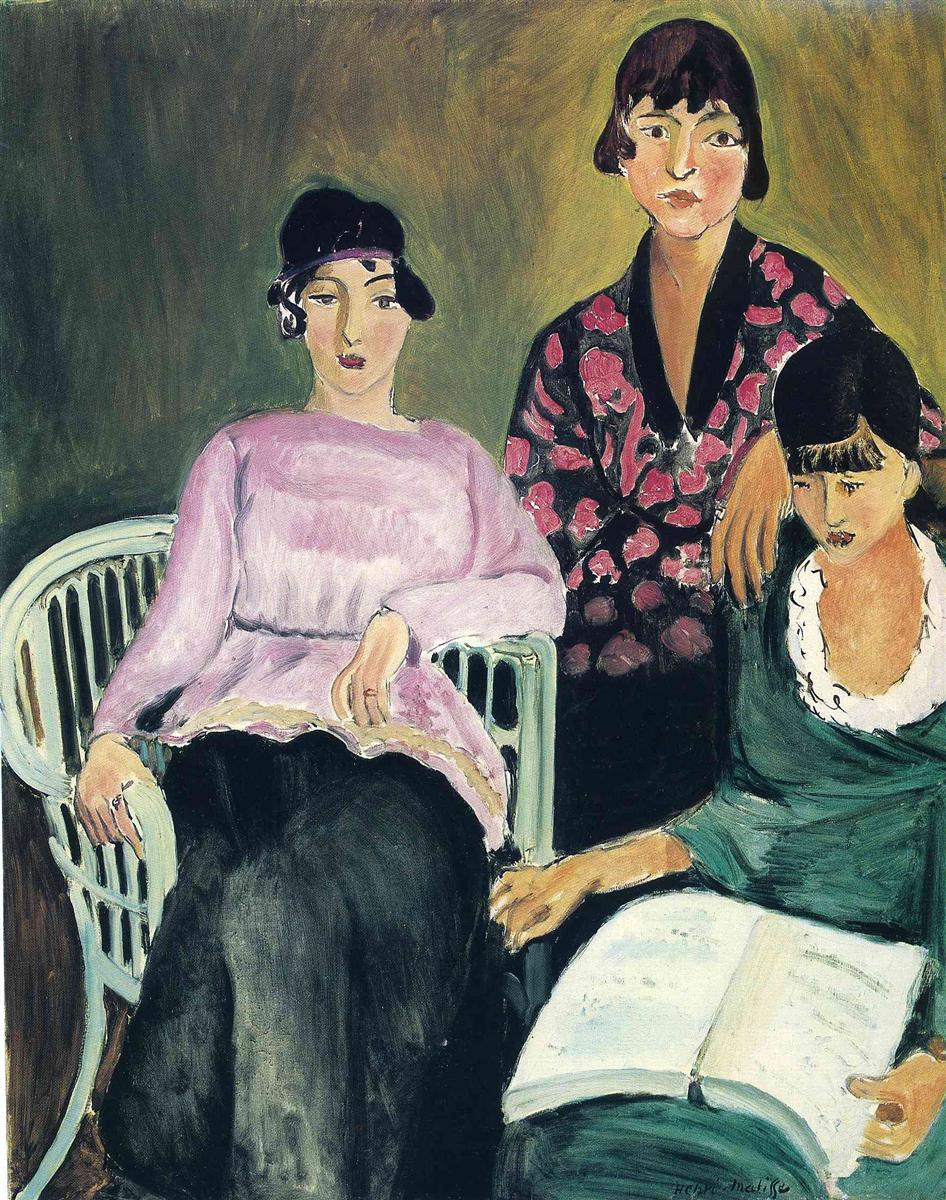

Henri Matisse’s “Three Sisters” (1917) arranges a trio of women in a shallow interior like actors pausing between lines. One in a lilac blouse reclines in a white cane chair to the left, another in a patterned black-and-rose jacket sits higher and nearer the center, and the third in deep green bends over an open book at the lower right. The background is an olive field brushed in slow arcs, neither wall nor landscape but a soft atmospheric curtain. Black contour lines cinch every form; color fills those outlines in broad, deliberate planes. The mood is reflective rather than celebratory: an everyday tableau of attention and companionship transformed into an orchestration of hue, value, and rhythm.

1917 And Matisse’s Turn Toward Disciplined Clarity

The date matters. By 1917 Matisse had pivoted from Fauvism’s incandescence to a language defined by reduction and poise. Wartime austerity encouraged essentials: black returned as a structural color; drawing became elastic but spare; color narrowed to tuned families rather than fireworks. At the same time, he leaned into interiors, fabrics, and domestic theater—the world that would expand in the Nice years just ahead. “Three Sisters” concentrates those tendencies. It is intimate and modern, withholding descriptive detail so that relationships—between figures, between colors, between patterns and quiet fields—can carry the picture’s meaning.

Composition As A Triad Of Attentions

The composition reads as a compressed triangle. The lilac-bloused figure forms the left anchor, her body slanting inward as the white caned chair sets a vertical frame. The patterned central figure occupies the apex, shoulders squared and gaze lifted slightly away from us. The reader at right provides the third point, her torso flowing diagonally down the page of the book toward Matisse’s signature. Between them, hands bridge gaps: the left sitter’s relaxed fingers echo the right reader’s focused grip; the central figure’s arm rests along a chairback like a hinge. These three attitudes—repose, quiet authority, and concentration—create a stable chord of human states that keeps the room serene even as the eye moves.

The Role Of The Chairs And The Stage Of The Floor

Matisse’s furniture is never neutral. The white cane of the left chair, drawn with just enough ribbing, becomes a luminous bracket that holds the lilac figure in place and amplifies the lightness of her blouse. The darker seat beneath the central figure, by contrast, recedes and throws attention to the embroidered jacket. Floor and lower wall merge into a shallow plane of mottled ocher and olive that behaves like a stage: not a mapped space with measurable depth, but a ground on which the bodies can be arranged as signs. This deliberate shallowness keeps every relationship legible at the surface.

Palette: Lilac, Rose, Green, And Olive In Measured Harmony

Color does the heavy lifting. The frosted lilac blouse and its pearly scalloped hem bring a cool sweetness that balances the denser blacks of skirts and hair. The central figure’s jacket—black patterned with rose—supplies the painting’s richest vibration, modern and ornamental at once. The reader’s robe and collar add a deep, calm green tuned to the olive background, welding figure and ground into a single climate. Small hot accents are rationed: a glint of lipstick, touches of warm cheek, the pink in the jacket’s blossoms. Because saturation is localized, chroma never overwhelms; instead, the colors function like parts of a chord held in tune by the black outlines.

Black Contour As Carpentry

Matisse’s black line is carpentry for color. Eyebrows, chair ribs, jacket edges, the lip of the open book, and the horizon of a skirt are all asserted with a flexible, confident stroke. It defines volume without shading and lets flat color breathe. In the lilac blouse a single line cinches the waist; in the jacket, short dashes stitch pattern to structure; along the book’s gutter, a crisp stripe folds paper decisively into space. Because the line does so much, modeling can remain minimal—flesh is a plane, not a lump—and the image stays both graphic and embodied.

The Three Faces: Variations On Presence

Matisse characterizes each face with a minimum of means. The left sitter’s features are soft and slightly distant, eyelids lowered as if attention drifts between the room and the self. The central figure’s gaze is steadier and cooler; her head is slightly larger in scale, pulling it forward in the picture’s hierarchy. The reader’s face is downturned, mouth closed into a small knot of thought; she is present through absorption rather than eye contact. This spectrum of presence—outwardly open, quietly commanding, inwardly focused—gives psychological depth without anecdote and invites viewers to find themselves somewhere along the scale.

Hands, Hems, And Edges: Small Passages With Big Work

Look long at the hands. The left sitter’s relaxed fingers echo the scalloped edge of her blouse; both forms flow with the same tempo and register the same light. The central figure’s hand is more assertive, hooked over a chairback, its knuckles aligned with the jacket’s edge like a functional brace in the composition. The reader’s hand grips the book lightly but decisively, thumb and forefinger orchestrating the angle that tilts the page toward us. These tiny choreographies bind bodies to objects and set the rhythm of looking.

The Open Book As A Silent Center

The open book is a tranche of whiteness that organizes the bottom right quadrant. Its pages are described by two biases of gray, a spine line, and barely suggested rows of text. The book is both prop and plane: a metaphor for attention and a compositional counterweight to the dense clothing around it. Its whiteness echoes the light cane chair at left, tying far corners of the painting into a single visual sentence. Because the book occupies the picture’s closest zone, it becomes the viewer’s portal into the scene, a quiet invitation to read along.

Brushwork That Balances Material Truth With Graphic Clarity

The surface is frank. In the olive ground, soft diagonal sweeps leave a visible grain that animates an otherwise plain field. The lilac blouse is handled with long, slightly translucent strokes that allow underlayers to cool the color; the scalloped hem carries thicker, creamier paint so that the eye registers a tactile change at the garment’s edge. The patterned jacket compresses short, loaded touches of rose against matte black, a tactile difference that keeps the pattern lively without exploding the surface. Everywhere the brushwork supports the drawing instead of obscuring it.

Pattern Versus Quiet Fields

Matisse calibrates ornament. The jacket’s roses provide the painting’s densest pattern; they sit precisely where the composition needs visual weight—near the apex of the triangular grouping. The rest of the picture is quieter: the lilac blouse is mostly unbroken, the reader’s green dress is a single deep field relieved only by the white collar, the background drifts evenly. This ratio grants the pattern authority and prevents it from dissolving the forms it adorns. Ornament is structure, not decoration; it anchors the central figure while the others create space and rest.

Space Built From Overlap And Value, Not Perspective

There is hardly any linear perspective. Depth arrives through overlap—a skirt in front of cane ribs, a shoulder in front of a wall—and through value differences. The darkest blacks pull forward; mid-tones recede; the paler fields of paper and cane sit in a middle light where the eye can rest. That value choreography keeps the picture shallow but convincing, like a stage set that trusts lighting and blocking more than architectural drawing.

Photographic Cropping And The Modern Group Portrait

The left figure’s skirt runs off the frame; the right figure’s forearm is cropped by the lower edge; the group is pressed against us. These choices feel modern and photographic, as if Matisse has stepped in close with a viewfinder rather than placing his subjects at courtly distance. The effect is intimacy without sentimentality: we are admitted to the room at arm’s length, near enough to feel among the chairs but not so close that the tableau collapses into anecdote.

The Eye’s Path Through The Picture

Most viewers begin with the lilac blouse—the brightest sustained area—then travel along the arc of cane ribs to the central figure’s patterned jacket. From there the gaze drops to the reader’s white collar, glides down the diagonal of the green bodice, and settles on the open book. The crisp spine line of that book then launches the eye back up toward the jacket’s dark V, completing a loop. Because each station on this route offers a change of tempo—broad field, tight pattern, sharp edge—the circuit can repeat indefinitely without fatigue.

Mood, Kinship, And The Ethics Of Reduction

“Three Sisters” avoids narrative labels. We do not know whether the women are biologically related, whether the book is a novel or a letter, whether a conversation pauses or never began. That refusal to explain keeps the painting open and dignified. Kinship is conveyed through proximity and rhythm: shared space, echoed blacks and whites, parallel postures, harmonized color families. Reduction—a few features, a few edges—becomes an ethical choice that grants the subjects privacy while inviting our sustained attention.

Echoes Of Tradition Without Imitation

The triangular grouping hints at classical composition, and the patterned jacket nods to the historical richness of textiles in portraiture. Yet Matisse declines chiaroscuro and finish. Instead he relies on large planes, visible touch, and a modern cropping that breaks with salon proprieties. In this way the painting converses with tradition while speaking a thoroughly twentieth-century language: clarity over illusion, relation over narrative, presence over anecdote.

The Central Figure As Pictorial Keystone

The woman in the black-and-rose jacket is the keystone. Her torso occupies the highest position; her garment supplies the strongest pattern; her hand rests where several contours meet. She ties left and right into one. The palette radiates from her—rose blossoms temper lilac nearby; black joins the readers’ dark hair and skirts; the jacket’s V mirrors the book’s V-shaped gutter below. Remove her and the painting splits; with her, the interior resolves into calm.

Sound And Silence In Color

Listen to the painting as if it were music. The lilac blouse is a high, cool note held steadily; the green dress enters as a lower, sustained tone; the jacket’s roses chatter lightly within a darker middle register; the black contours provide percussion. The olive ground hums softly behind. Matisse composes not just with sight but with imagined sound, balancing chatter and drone, beat and sustain, until the chord of the room feels right.

Why “Three Sisters” Endures

The picture endures because it captures how color and line can make kinship visible without telling a story. It offers rest without inertia, intimacy without intrusion. It shows a master painter using modest means—three bodies, two chairs, a book, a patterned jacket—to build a complete world of relations. In that world, attention itself is the protagonist: attention to reading, attention to one another, attention to form. The longer we look, the more the painting gives, not by revealing secrets but by confirming its clean, generous order.