Image source: wikiart.org

A Shoreline Frieze That Breathes

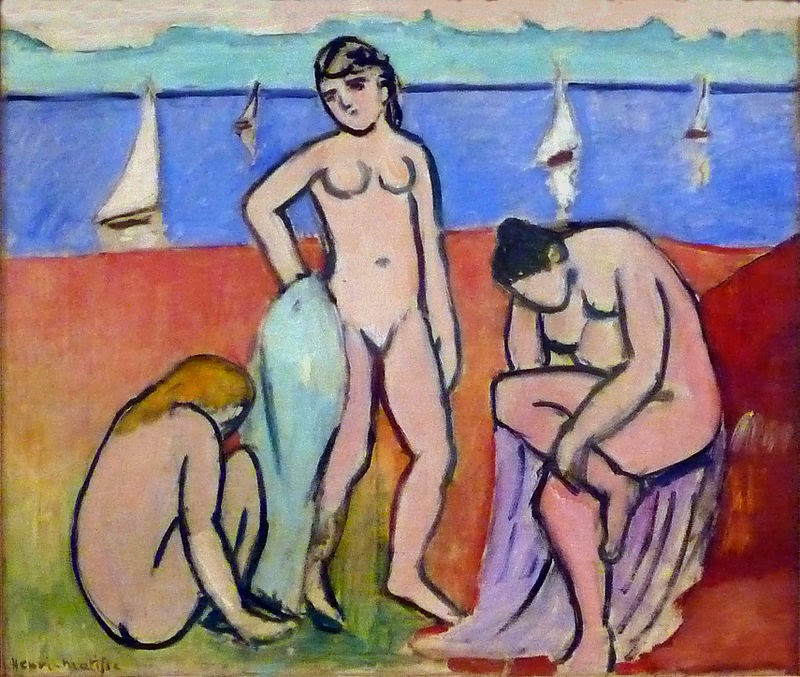

Henri Matisse’s “Three Bathers” (1907) distills a timeless seaside ritual into an image of clarity and poise. Three nude women occupy a red sandbar beneath a band of blue sea and pale sky. Their bodies are bounded by decisive dark contours, modeled only lightly by tonal shifts of rose, ochre, and lavender. In the marine distance, white sails punctuate the horizon like notes on a staff. Everything in the painting is pared down to essentials—the stance of each figure, the geometry of colored fields, and the exacting line that separates body from air—yet the scene feels alive, tender, and unforced. The picture belongs to the moment when Matisse moved from the flashing brushwork of early Fauvism toward a calmer, classical language in which color planes and contour carry the meaning.

From Fauvist Spark to Classical Calm

The years around 1907 are pivotal for Matisse. After the blazing experiments of 1905 in Collioure, he began to consolidate the discoveries of pure color and simplified form into compositions that read like modern frescoes. “Three Bathers” is a perfect statement of this transition. The chroma remains bold—vermillion shore, cobalt sea, milky sky—but the application is more even, the shapes more architectonic, and the drawing more authoritative. Matisse is not abandoning intensity; he is focusing it, giving color a stable architecture so that emotion arises from proportion and placement as much as from hue.

Composition Built on Bands and Triads

The picture is organized by three long horizontal bands—sky, sea, and land. That simple stratification is then countered by the triangular arrangement of the figures. The leftmost bather crouches, compact and inward. The central figure stands in contrapposto, weight on one leg, head inclined in a reflective arc. The figure at right sits on the red ground, bent forward as she adjusts or removes a translucent drape. Each body adopts a different attitude toward gravity and space, and together they form a rhythmic progression from compression to expansion to contraction. The result is a composition that feels both static and musical, a frieze that breathes.

Line as Law and Lilt

Nothing in “Three Bathers” is as declarative as the contour line. Drawn with a charged black that occasionally softens into blue, it states with confidence where forms begin and end. Around calves and forearms it thickens; across clavicles and cheekbones it thins, becoming almost a whisper. This control of weight gives the line its music. It does not imprison color; it animates it. The contour also pays homage to Matisse’s admiration for Ingres and for the clarity of classical relief sculpture, while the looseness of its edge keeps the bodies tender and human.

Color Fields with Purpose

Matisse’s color is never merely descriptive. The red of the beach is warmer and more saturated than the skin, so that flesh appears luminous even when modeled with only a few lilac shadows. The sea is an unbroken field of blue, broken only by verticals of white sails that push the eye upward and outward. The sky’s greenish band at the top adds a cool, lucid lid to the composition, tightening the harmony. The palette is deliberately limited—flesh pinks, coral red, ultramarine, sky green, charcoal black—so that every note counts. Color here states relationships rather than facts; it says warm meets cool, vertical interrupts horizontal, body anchors landscape.

A Modern Pastoral

The subject of bathing belongs to the long pictorial tradition of Arcadia, yet Matisse strips away mythological pretense. There are no gods, no nymph attributes, no narrative props beyond a towel or veil. The bathers look neither coy nor heroic. They are absorbed in their own small gestures—resting, standing, adjusting cloth—so that the viewer’s gaze becomes a companion rather than a captor. The mood is not erotic, but serene; not anecdotal, but emblematic. “Luxury,” painted by Matisse the same year, seeks a similar monumentality by using three nudes; “Three Bathers” translates that ambition into a more intimate scale, closer to a portable fresco than a public manifesto.

The Poetry of Gesture

One of the painting’s most affecting qualities is the individuality of the three postures. The crouching figure on the left forms an almond-shaped mass, head bowed, arms enclosing the knees. She reads as a seed within a shell, a compact unit of repose. The central model stands upright, a column with a soft S-curve. Her tilted head and the cool drape at her side make her the picture’s quiet axis. The rightmost figure bends forward, one leg lifted, arms converging at the shin as if to remove a stocking or sand from her foot. The sequence invites the eye to experience the body’s possibilities of balance, inwardness, and care.

Depth Without Illusionism

Matisse suggests space with the lightest touch. The horizon is high, which compresses the field and pushes the figures toward us. The red ground reads as a broad plane because it is uniform in color and texture, interrupted only by the bodies themselves and the lavender veils. No cast shadows anchor them; instead, overlapping and scale carry the depth cues. The sailboats behind act like scale markers and also as little breath marks in the blue strip. This shallow, tapestry-like space is a hallmark of Matisse’s maturity. It converts the canvas from a window into a wall—something that asserts itself in the room as a stable, calming surface.

Brushwork and Surface

Up close, the paint handling reveals a disciplined restraint. The red ground is laid in with even, slightly matte strokes; the sea’s blue is smoother and less variegated; the skin tones contain small, deliberate inflections—lilac along the stomach, pale jade near the jawline, a blush of carmine at knees and cheeks. These accents keep the flesh from reading as flat poster color while refusing any return to academic modeling. The lavender of the veils is laid so that the canvas weave occasionally appears through, giving the cloth an airy transparency that keeps it from weighing down the design.

The Boats as Counterpoint

The boats do more than populate the horizon; they counterbalance the human scale with an architectural beat. Placed at irregular intervals, they punctuate the blue band and prevent it from becoming a dead zone. Their white triangles also rhyme with knees, elbows, and drape angles, tying background to foreground through echoing geometry. Matisse often uses small motifs this way—as crisp off-beats that sharpen the rhythm of the whole.

Human Presence Without Psychological Drama

The faces are simplified to sign-like clarity: almond eyes, a single shadow under the nose, a small mouth. Expression lies less in features than in placement and tilt. The central figure looks toward her companions, eyes half-lidded in a manner that reads as calm curiosity; the other two avert their gaze, fully absorbed in their private acts. This creates an atmosphere of companionable solitude. We are invited to watch, but we are not invited to judge. The ethical atmosphere is one of ease and dignity, consistent with Matisse’s lifelong aim to make paintings that offer “an armchair for the mind.”

The Ethics of Simplification

To simplify is risky; it can harden into cartoon or diagram. Matisse prevents this by caring for transitions. Where sea meets shore, a slim violet line moderates the clash of blue and red. Where a thigh meets the belly, the outline swells and then thins. Where a shoulder rises against the sky, a tiny rim of pale blue slips between black line and pink flesh, letting air circulate around the body. These micro-decisions are invisible at first glance, but they keep the picture open, breathable, humane.

Echoes of the Studio and the Sea

“Three Bathers” carries the memory of both studio discipline and plein-air sensation. The clarity of the bands and contours feels designed at the easel; the particular coolness of the sea-blue and the brightness of the sand-red feel remembered from direct coastal light. Matisse’s greatness lies in joining these two ways of seeing—observed chroma and constructed form—so that the painting reads as both lived and composed.

Relation to Matisse’s Bathers and Beyond

Bather subjects recur throughout Matisse’s career, from the rough-hewn “Blue Nude” (1907) to the monumental dancers and musicians of 1910 and later to Nice-period odalisques. “Three Bathers” stands near the beginning of that arc, showing how the artist turns a living model into a modern hieroglyph of leisure and plenitude. Compared with the knotted, muscular energy of “Blue Nude,” these figures are smoother and more planar. Compared with the later odalisques, they are less upholstered by pattern and more elemental. The work reads as a bridge—from the experimental heat of Fauvism to the stable lyricism of Matisse’s mature decorative style.

Harmony of Ratios

Matisse thought in ratios as much as in colors. The red ground occupies just over half the height; the sea and sky divide the remainder in slightly unequal parts, which prevents the composition from feeling evenly sliced. The standing figure’s head breaks the horizon, welding foreground to background. The croucher’s head sits below the horizon; the seated figure’s head just grazes it. This laddering of heights knits the trio into the design. Even the drape in the center hangs at a diagonal that counters the long horizontal seam of the sea.

Tactility and Temperature

The painting’s temperature shifts with remarkable control. The left side, with its crouching figure and cooler shadows, has a quiet, internal chill; the center warms where the standing figure catches the full value of the red ground; the right cools again with the seated bather’s lavender veil. The viewer senses warmth on skin and cool on cloth. This alternation of hot and cool zones is as important to the work’s mood as the drawing itself.

The Nude and Modern Modesty

Matisse’s nudes are fully seen but never exposed for scandal. In “Three Bathers,” modesty is encoded not by drapery but by posture and tone. The bodies’ surfaces are matte rather than polished; the gestures are functional rather than theatrical; the viewer’s distance is respected by the lack of seductive detail. This is a modern modesty that does not deny the body’s beauty; it simply treats it as a fact of existence among light, air, and sea.

Seeing the Painting in Person

If you encounter the painting in a gallery, begin at the central figure’s face, then travel down the drape to her feet. Let your gaze swing left to the crouching oval and notice how the spine is suggested with a single curving line. Cross the canvas to the right and watch the arc of the seated bather’s back meet her lifted leg; the contour compresses, then opens again at the knee. Step back and the three postures blend into a single, slow gesture across the shore. Step close and the surface resolves into flat, confident patches whose edges show the artist’s hand.

Why “Three Bathers” Endures

The picture endures because it establishes a world of sufficiency. There are only a few colors, a few shapes, and three bodies, yet nothing feels lacking. Luxury here is not possession but leisure, not ornament but order. In an age that often equates ambition with complication, Matisse demonstrates that ambition can take the form of clarity. The painting gives the viewer a stable place to rest the eye and, by extension, the mind. It is an image of calm that has been earned through artistic decision, stroke by stroke, line by line.