Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

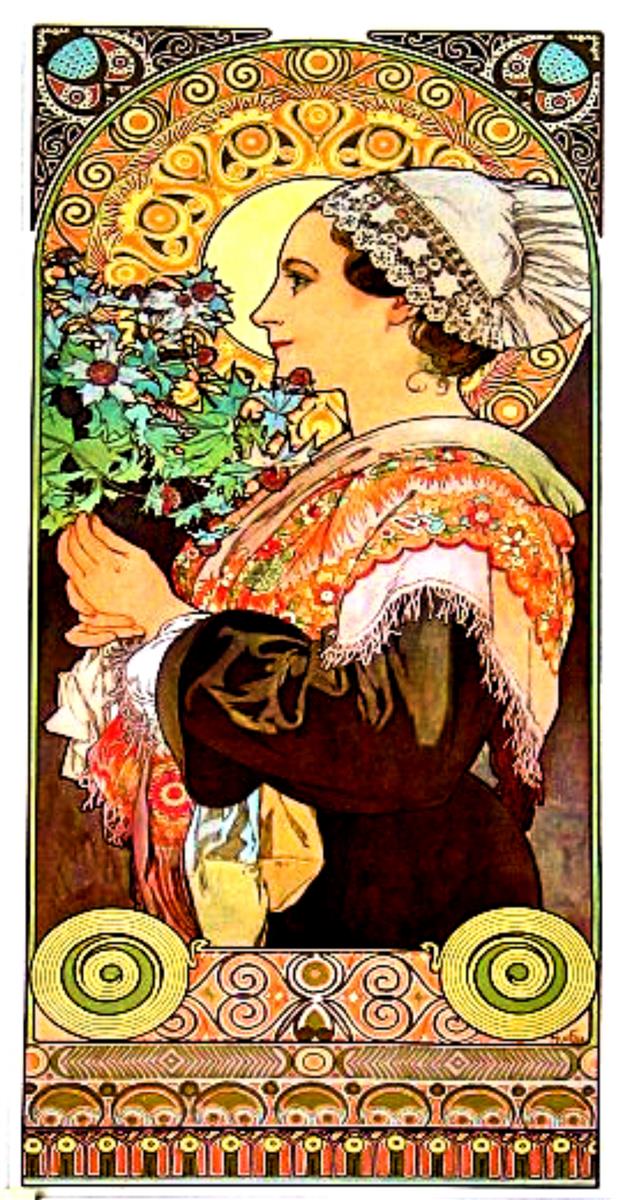

Alphonse Mucha’s “Thistle from the Sands” radiates a warm, hymn-like glow. A young woman in profile advances from left to right, carrying a dense bouquet of thistles. Behind her, an aureole of concentric circles blooms like a rising sun, while an intricate, jewel-box frame of spirals and rosettes binds image and ornament into one continuous rhythm. Her scarf, edged with lace and embroidered with flowers, spills an abundance of color across a dark dress, and the bottom register resolves into a patterned plinth that feels half-architectural, half-textile. The panel is classic Mucha: a union of figure, botany, and design where every curve, from fingertip to halo, participates in a single decorative sentence.

Historical Moment

Dated 1902, the work belongs to Mucha’s mature Paris period, when he perfected the tall, arched panel featuring a single allegorical woman fused with a specific flower, gem, season, or virtue. The formula was no mere template; it was a laboratory. Within it he refined how line could carry emotion, how color could persuade, and how ornament could do the narrative work a background once did. “Thistle from the Sands” continues the artist’s conversation with popular illustration and fine art, demonstrating how a print intended for wide circulation could achieve the dignity and intimacy of a painting.

The Promise Inside The Title

The title is a small poem. Thistles are hardy plants that grow where soil is poor, where wind scours, where other flowers fail. “From the Sands” strengthens that character, suggesting a landscape of dunes or thin earth where beauty arrives as resilience, not luxury. Mucha turns that botanical fact into allegory. The woman carries toughness disguised as bloom. She is grace that learned how to endure. The bouquet’s barbed nature is softened by her calm expression and the prayer-like nest of her hands, so that we feel not threat but blessing. Beauty survives, and that survival is the message.

The Woman As Allegory Of Offering

Mucha’s heroines are rarely passive; they act through gesture. Here the figure’s hands cradle the thistles as if bringing them forward for our acceptance. The slight lean of the body and the firm path of the profile establish motion without haste, a procession measured by gratitude. Her headscarf and lace coif, rendered with loving attention to textile and regional craft, connect her to the earth as surely as the plants she holds. She is neither priestess nor fashion plate. She is a celebrant of common things, someone whose dignity grows from care.

Composition As Architecture Of Light

The composition is an arch around an arch: a tall niche frames the figure, and within it a circular halo of coiling motifs expands behind her head. The two discs—one smaller, one larger—read as sun within sun, or perhaps sun and moon nested, a reminder that the thistle’s stubborn life belongs to cycles of day and season. Mucha builds the halo from repeats—tight curls, beaded rings, and petal-like ovals—so that the light feels woven rather than poured. The bouquet mirrors this density with its own bristling clusters. Profile, halo, and thistle together make a triad: human, cosmic, and earthly, each echoing the other’s form.

Line That Sings

This panel shows why Mucha’s line remains so persuasive. Contour is consistent yet elastic, swelling slightly to give the cheek bone weight, thinning over the lace to keep air in the fabric. The whiplash curves that define Art Nouveau appear in the arabesque of the scarf’s edge, in the spiraling ornaments of the frame, and in the tendrils of foliage that curl outward from the bouquet. No stroke is idle. Line not only contains color; it conducts rhythm. Our eye moves the way a melody moves—calmly, inevitably—from halo to face to hands to thistle and back again.

Color As Climate

The palette is a negotiated truce between warmth and coolness. Golds and ambers flood the halo and lower registers; coral, vermilion, and peach bloom in the scarf’s embroidery; olives and blue-greens inhabit the bouquet and ornamental corners; the dress holds everything in its dark, steady mass. The effect is a microclimate of late afternoon, when sunlight has thickness and plant color deepens. Mucha uses this climate to make the thistle—normally muted in hue—read as handsome rather than austere. Accents of light on leaves and flower heads feel like grains of sand catching sun, a color metaphor that returns us to the title.

Pattern As Memory And Meaning

The frame is not a neutral border. It is a repository of signs. In the spandrels at the top corners, circular medallions hold crescent-like forms, moon seeds that repeat the larger halo beneath. The broad band under the figure gathers spirals, lozenges, and bead rows that resemble woven tapes and carved wood—motifs that suggest folk craft without copying any single source. Mucha admires regional pattern as a living language, not a museum specimen. He places it where architecture would have carved capitals or friezes, dignifying the everyday arts of women—lace making, embroidery, spinning—as equal to stone.

The Halo And The Secular Sacred

Mucha’s halos are secular sanctities. They do not declare sainthood so much as elevate attention. By giving the woman a radiant disc, he asks us to look at her with the seriousness we reserve for icons, and thereby look at her subject—the thistle—with the same seriousness. The halo’s geometry also solves a compositional problem: it isolates the facial profile from the busy garden of ornament and foliage, ensuring that the viewer’s first recognition remains human. The sacredness here is a function of design serving empathy.

Costume And The Grammar Of Touch

The shawl’s fringe is a small masterpiece of tenderness. Each thread is indicated without pedantry, a quick calligraphic note that convinces the hand. The lace cap sits with believable weight and transparency across the hairline. The sleeve of the dark dress gathers and releases light in broad, confident planes. These touches matter because they ground the allegory in sensation. We are not simply told that resilience is beautiful; we feel the warmth of cloth, the catch of a thorn, the comfort of a scarf, and the fragrance of a bouquet carried close to the face.

Lithographic Thinking And Flatness With Depth

Mucha’s panels were designed to translate gracefully into color lithography. The image demonstrates the virtues of that process: flat areas of tone bounded by assured contour, gentle gradients where necessary, and layered textures that suggest embroidery or gilding without relying on paint’s thickness. The resulting flatness is a kind of visual honesty. Instead of aping oil’s illusions, the print embraces its own materials. Yet within this flatness, Mucha still constructs depth—foreground hands in front of flowers, the figure in front of the halo, the halo in front of a patterned sky—so that the space breathes while staying decorative.

The Botany Of The Bouquet

Mucha rarely treats flowers as mere props. Thistles are structurally striking: globes, bracts, spines, and serrated leaves that lend themselves to line. He capitalizes on those facts, building a bouquet that bristles like a small architecture. The flower heads cluster in rhythmic upbeats; the leaves swirl into scrolls that rhyme with the frame. By rendering the thistle as handsome geometry, he invites us to reconsider what counts as beautiful. The plant’s reputation as stubborn or prickly becomes a virtue: endurance with grace.

Gesture, Breath, And Profile

The profile is classical, concise, dignified. The lips part slightly as if to drink the bouquet’s scent, and the nose, chin, and brow align with a calm clarity that calls to mind antique cameos. This classical restraint offsets the panel’s exuberant ornament. It also channels energy forward, the way a ship’s prow directs a wake. Her hands intensify the motion: they are clasped but not clenched, fingers curved in a gesture that reads as both offering and prayer. The whole figure seems to move without walking, a procession achieved by breath alone.

The Lower Register As Stage

Mucha often dedicates the bottom of his panels to a horizontal band that operates like a stage or altar. In “Thistle from the Sands,” this plinth is thick with spirals, rosettes, and scalloped rows, culminating in two circular bosses that stabilize the design like heavy stones. Read metaphorically, the base is the ground itself, the “sands” from which the thistle rises. Read purely visually, it is a counterweight that prevents the tall composition from floating away. The balance feels architectural: the human figure stands upon a crafted foundation, as a statue would upon a pedestal.

Folk Memory And Personal Geography

Even when Mucha worked in Paris for a cosmopolitan public, he carried the textures of his Moravian roots. The lace, the floral shawl, the preference for warm metallic golds, and the respect paid to peasant craft all fold his homeland into the myth of the modern city. “Thistle from the Sands” can be read as a love letter to that continuity. The woman’s costume is not literal ethnography; it is a composite of cherished types, arranged with care so that viewers from many places can recognize something of their own elders and festivals.

Time Of Day And Interior Weather

Although the panel presents no landscape beyond foliage and halo, it communicates a time of day: late afternoon moving into evening. The golds deepen toward amber, and the bouquet’s cools feel more saturated, as if sun sits low and air carries weight. This interior weather suits the title’s suggestion of dunes and lean ground. The figure’s movement forward becomes a migration through light, bringing the day’s resilience with her.

Comparisons And Continuities

Placed beside Mucha’s other floral personifications—the four “Flowers,” the “Precious Stones,” the “Seasons”—this panel keeps the family resemblance yet asserts its own argument. Many sister works emphasize languor or theater; this one emphasizes purpose. The halo is denser, the bouquet tougher, the hands more devotional. It remains ornamental, but it also feels ethical: beauty as care for what is difficult.

Reading The Face

Mucha’s faces are famously idealized, but within that ideal he allows local character. Here the jaw is strong, the cheekbone honest, the nose unexaggerated. A trace of smile attends the lips, not coquettish but satisfied. The gaze looks slightly upward, as if acknowledging the worth of what she carries. These choices transform the figure from mere carrier to advocate. She believes the thistle has value; therefore we do too.

Why The Image Endures

The endurance of “Thistle from the Sands” lies in its reconciliation of opposites. It is richly decorated yet morally plain. It is flat yet full of air. It is rooted in folk memory yet cosmopolitan in design. It celebrates a thorny plant without softening it into something it is not. In a world that often confuses luxury with beauty, the panel proposes a different equation: beauty equals perseverance arranged with love.

Conclusion

Alphonse Mucha’s 1902 panel turns a humble species into a heroine and a strip of paper into a sanctuary of light. The halo’s spirals hum like a chorus, the shawl’s embroidery brings the labor of hands into the foreground, and the thistle’s spines take their place among pearls and petals as worthy ornaments of the human world. “Thistle from the Sands” asks the viewer to receive an offering and, in receiving it, to remember that culture begins with what we choose to honor. Between the dunes of scarcity and the gardens of abundance, Mucha plants this image like a resilient bloom.