Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

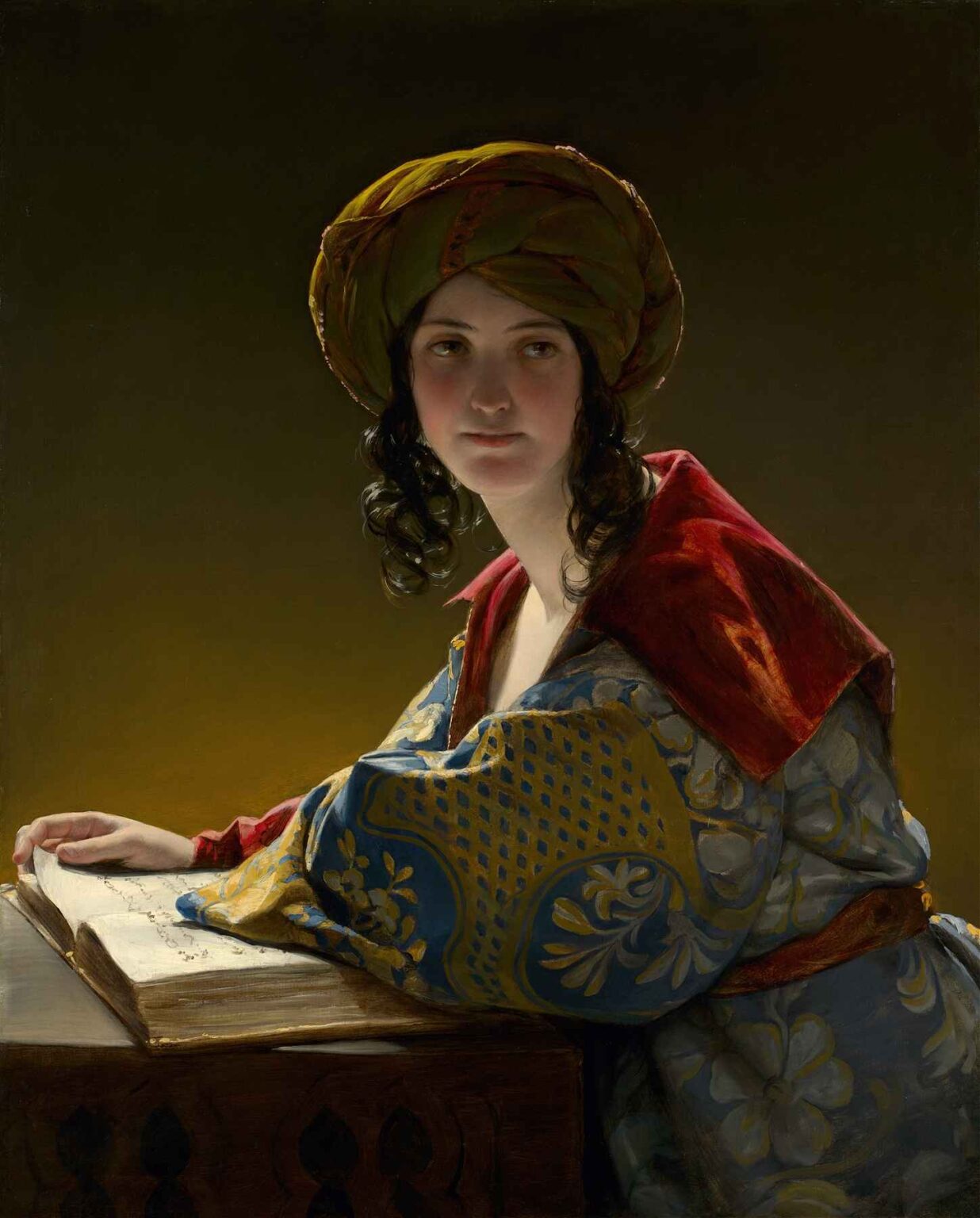

Friedrich von Amerling’s The Young Eastern Woman (1838) is a luminous masterwork that exemplifies the Romantic fascination with the exotic and the timeless beauty of idealized portraiture. Painted during the height of Orientalism in 19th-century European art, this work not only captures a moment of serene introspection but also reflects the broader artistic and cultural sensibilities of its time.

Amerling, one of the most prominent Austrian portrait painters of the Biedermeier era, brings to this painting his hallmark blend of technical precision, psychological subtlety, and poetic atmosphere. The subject—a contemplative young woman dressed in richly patterned, Eastern-inspired robes—sits beside a thick, open book, suggesting both elegance and intellect. Bathed in warm, directional light, her soft features, expressive gaze, and opulent garments evoke a sense of stillness and inner life that transcends mere decorative portraiture.

In this analysis, we will explore the painting’s stylistic elements, historical context, symbolic content, and enduring influence, situating it both within Amerling’s body of work and the larger tradition of 19th-century Orientalist and Romantic painting.

Friedrich von Amerling: A Master of Portraiture

Born in 1803 in Vienna, Friedrich von Amerling was one of the most sought-after portraitists in the Austro-Hungarian Empire. His clientele included aristocrats, intellectuals, and the bourgeois elite. Amerling studied in Prague, Vienna, and later at the Academy in Paris, where he came under the influence of leading French painters, particularly Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres and the early Romantics.

Throughout his career, Amerling’s portraiture was celebrated for its lifelike detail, harmonious color palette, and psychological depth. He had a unique ability to endow his subjects with both physical presence and inner complexity—qualities that are fully evident in The Young Eastern Woman.

Though not one of his royal commissions, this painting reveals Amerling at his most imaginative and intimate. It is a meditation on femininity, mystery, and the allure of the unfamiliar.

Composition and Form

At first glance, The Young Eastern Woman captivates with its simplicity. The sitter occupies the majority of the frame, turned slightly to the viewer’s left yet meeting our gaze with quiet directness. Her hand rests gently on an open book, one finger still inserted between its pages, as though momentarily paused in reading.

This half-turn posture, combined with the soft, golden lighting, creates a dynamic balance between stillness and presence. The figure emerges from a dark, indeterminate background, creating a dramatic chiaroscuro effect that draws all attention to her face and upper body. Amerling carefully arranges the composition to emphasize the model’s luminous skin, dark curls, and richly colored garments.

There is no visible setting or narrative context—only the sitter, the book, and her quiet, enigmatic expression. This isolation of subject creates a timeless, contemplative atmosphere. It also elevates the woman to an almost iconic status, suspended between the real and the ideal.

Color, Light, and Texture

Color plays a central role in the emotional tone of the painting. The backdrop is a gradient of olive to deep brown, creating a warm, enveloping field from which the figure subtly emerges. The most vivid colors are reserved for the woman’s clothing: a brilliant red shawl, a patterned blue robe with gold detailing, and an olive-green turban adorned with subtle folds and highlights.

Amerling’s treatment of fabric is particularly noteworthy. The intricate patterns and luxurious drapery are rendered with meticulous care, yet they never overwhelm the composition. Instead, they frame and enhance the quiet elegance of the woman’s face, which is painted with smooth, delicate transitions between light and shadow.

The light source—positioned slightly above and to the left—illuminates her forehead, nose, and cheeks, creating gentle modeling that emphasizes her youth and softness. Her hand, resting on the page of the book, receives equal care, its anatomical precision matched by its graceful positioning.

This interplay of rich texture and soft light creates a palpable atmosphere, transforming the canvas into a living presence. Amerling uses these visual strategies not only to impress the viewer with painterly skill but also to evoke an emotional response rooted in admiration, curiosity, and a sense of reverence.

The Allure of the East: Orientalism and Romanticism

The Young Eastern Woman must also be understood within the larger framework of Orientalism, a widespread trend in 19th-century European art, literature, and design. Fueled by colonial expansion, increased travel, and the romanticization of distant cultures, Orientalist art presented the East—particularly the Middle East and North Africa—as a land of mystery, sensuality, and exotic beauty.

Though this movement was often shaped by Western fantasies and stereotypes, it also offered artists a new visual vocabulary: opulent fabrics, distinctive architecture, unique physiognomies, and a freer approach to composition and color.

Amerling’s painting taps into this aesthetic curiosity, but does so with restraint. The sitter is not overtly sexualized or fetishized—a common trait in more theatrical Orientalist works. Instead, she appears dignified, poised, and quietly intelligent. Her clothing is suggestive of Middle Eastern fashion, but Amerling doesn’t strive for strict ethnographic accuracy. The “Eastern” elements function as symbols of otherness and poetic distance, creating a portrait that is as much a dream of the East as a depiction of a specific cultural identity.

This approach places the painting at the intersection of Orientalism and Romanticism. The subject becomes a muse-like figure—exotic, intellectual, and unknowable—crafted to embody the Romantic ideals of beauty, mystery, and introspection.

The Book: Symbol of Knowledge and Intimacy

One of the most intriguing features of the painting is the open book that the woman is reading. Books in portraiture often serve as indicators of intelligence, education, and personal depth. In Amerling’s work, the book adds an additional layer of psychological richness.

The woman’s hand marks her place as she looks up from the page, as though interrupted mid-thought. Her expression is not passive but gently curious, as if reflecting on what she has just read. The presence of the book humanizes her—moving the portrait away from pure aestheticism and toward a quiet intellectualism.

It also serves as a compositional anchor, grounding the lower half of the painting and introducing a horizontal counterbalance to the strong vertical flow of the figure and clothing.

Symbolically, the book invites the viewer into the world of the subject, not just visually but imaginatively. It suggests a narrative interiority, a life of thought and study behind the composed exterior.

Psychological Presence

Perhaps the most compelling aspect of The Young Eastern Woman is its psychological resonance. Unlike many academic portraits of the period, which emphasize status and formality, this work seems to capture a fleeting, introspective moment. The woman’s gaze is not confrontational, but it is engaged; she is aware of being seen, but not performing.

This psychological nuance is a signature of Amerling’s best portraits. He consistently sought to capture the inner life of his subjects—not through dramatic gesture or emotional excess, but through subtle posture, lighting, and facial expression.

In this painting, the subject’s slight tilt of the head, the touch of shadow under the eyes, and the soft flush of her cheeks all work together to suggest a personality that is thoughtful, grounded, and quietly aware of her surroundings.

Her expression is hard to define—somewhere between curiosity, contemplation, and gentle amusement. This ambiguity invites the viewer to linger, to wonder, and to project meaning onto her silence.

Comparison to Contemporaries

Amerling’s The Young Eastern Woman can be fruitfully compared to the works of other 19th-century portrait masters:

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres: The French Neoclassicist’s emphasis on elegant line, idealized form, and exotic subjects strongly influenced Amerling’s portraiture, especially in the rendering of fabric and facial serenity.

Franz Xaver Winterhalter: A fellow court portraitist, Winterhalter painted aristocratic women with luminous surfaces and decorative splendor, but often lacked Amerling’s psychological depth.

John Frederick Lewis: Known for his more ethnographically detailed Orientalist scenes, Lewis presents a contrast to Amerling’s poetic stylization.

Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun: Though working in an earlier generation, her ability to render charm and intelligence in female sitters aligns with Amerling’s goals.

What sets Amerling apart is his ability to synthesize these influences into a portrait that is intimate, idealized, and emotionally layered without ever veering into caricature or sentimentality.

Legacy and Reception

While The Young Eastern Woman may not be as widely known as some of Amerling’s royal commissions, it remains one of his most evocative and refined portraits. It encapsulates the Biedermeier ideal of quiet domesticity and personal inwardness, while simultaneously drawing on the broader currents of Romanticism and Orientalist aesthetics.

The painting has been praised for its harmonious composition, masterful technique, and emotive restraint. Art historians have noted its influence on later Austrian portraiture and its place within the wider European fascination with the East during the 19th century.

Today, it continues to resonate not only as a beautiful portrait but as a cultural artifact—one that reveals as much about 19th-century European ideals of femininity and foreignness as it does about the individual it depicts.

Conclusion

Friedrich von Amerling’s The Young Eastern Woman is a remarkable blend of technical brilliance, aesthetic sensitivity, and quiet psychological intensity. Painted in 1838, it transcends the genre of portraiture by combining the decorative richness of Orientalist fashion with the contemplative stillness of Romantic introspection.

Through meticulous brushwork, controlled lighting, and symbolic restraint, Amerling invites viewers into a moment of serene contemplation—a timeless encounter between subject and observer. The painting reflects the values of its era while offering a universal meditation on beauty, thought, and presence.

More than a portrait, The Young Eastern Woman is a visual poem—rich in color, detail, and mystery—inviting us not only to look, but to reflect.