Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

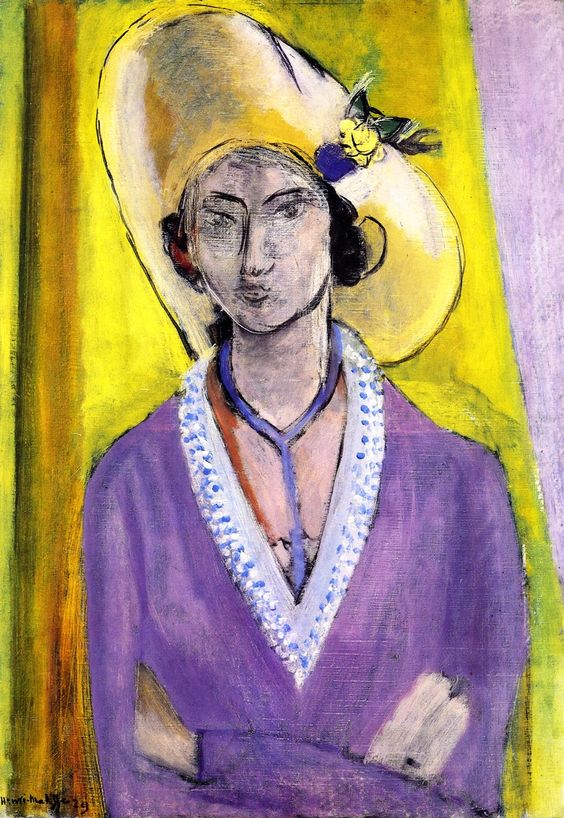

Henri Matisse’s “The Yellow Hat” (1929) is a concentrated demonstration of how portraiture can be rebuilt from color, contour, and the measured play between ornament and structure. The sitter stands frontal, arms folded, her features drawn in a few dark, economical lines. A luminous, oversized hat dominates the upper half of the canvas, its brim tilting into space like a shallow golden saucer. The coat is violet—cool, dense, and edged with a stippled white trim that reads as both lace and painted light. Behind her, a radiant yellow field creates an aura that fuses sitter and setting into a single, modern icon. The painting is not interested in psychological anecdote; it is committed to the orchestration of intervals—yellow against violet, soft planes against incisive line, garment geometry against the pliant oval of a face. In this balance, Matisse finds a new kind of presence: neither descriptive realism nor decorative flatness, but a lucid equilibrium that keeps the eye alert and at ease.

A Portrait From The Late Nice Years

Painted at the end of the 1920s, “The Yellow Hat” belongs to Matisse’s late Nice period, when rented rooms functioned as flexible studios and lighting theatres. While many works from these years depict reclining odalisques and saturated interiors, the portrait here focuses attention on a single figure compressed against a shallow ground. The Nice light—diffuse, reflective, and kind—still governs the atmosphere, but the apparatus of screens, carpets, and patterned curtains gives way to a simplified stage of color. The sitter’s hat and coat become architectural elements; the face, traced in calligraphic economy, is a hinge where the painting’s systems meet.

Composition As A Dialogue Of Triangles And Ovals

The composition is a study in geometry made human. The dominant triangular form of the coat anchors the lower half of the canvas, its apex pointing upward toward the chin. This triangle is countered by the grand oval of the hat, which spans the upper register and softens the rigor of the garment below. Between them resides the oval of the face—smaller, more pliant, and alive with linear inflection. The arms fold across the base like a secondary horizontal, closing the form and keeping the eye within the frame. A vertical strip at the left edge—greenish and cool—acts as a jamb or pilaster, a subtle architectural cue that stops lateral drift and steadies the central icon. Matisse positions each element as if setting stones in a wall; the locking of triangle and oval produces an image that feels inevitable.

Color As Architecture And Temperature

Color builds both mood and structure. The yellow of the hat and background is not a single note but a chord that moves from lemon to golden ochre to pale straw, with cool grays and lilacs tempering its glow. This high, warm register is measured against the coat’s violets, which range from blue-leaning periwinkle in the shadow to a redder lavender in the lights. Yellow and violet are near-complementary; their encounter generates a vibration that is intense yet stable because Matisse handles both with moderation. The white edging—painted as a dotted ribbon of paint—cools the heat at their juncture and acts as a thermal gasket between warm head and cool torso. Flesh is described by thin, silvery passes that borrow from both camps: the cheeks collect warmth from the hat, while the neck and hands pick up cooler lilac from the coat. The palette is limited and tuned, a small orchestra playing in tune rather than a crowd of soloists.

Drawing, Contour, And The Authority Of The Line

The sitter’s presence is secured by line. Matisse draws the features with a few confident strokes: a single curve for an eyebrow, an angled break for the nose, a compressed “M” for the mouth, and slanting ellipses to seat the eyes. These marks are not descriptive details; they are structural calligraphy, establishing the face as a readable mask without over-specifying it. The coat’s lapels are written more heavily to hold the garment’s geometry. The hat brim is traced in a broken, searching line that lets the ground breathe through, a choice that prevents the hat from becoming a static halo. The folded arms are drawn with abbreviated curves and flat planes that feel tactile but never stiff. Everywhere the edge is living—tightening where it must bear weight, loosening where color can do the work.

Pattern, Trim, And The Discipline Of Ornament

At first glance the beaded white trim and the small blossom on the hat read as flourishes. In fact, they are structural devices that meter time and keep large color fields from congealing. The stippled edge along the lapels and neckline is not simply lace; it is a rhythmic phrase that modulates the transition from violet to flesh. Each dot is a micro-highlight, and together they operate like a slow arpeggio leading the eye up the garment to the face. The hat’s flower—lemon petal and violet accent—repeats the canvas’s dominant dyad in miniature. This echo makes the hat’s mass feel integrated rather than applied. Ornament here is discipline, not indulgence.

The Hat As Solar Architecture

Matisse often uses headgear to set the key of a portrait; in “The Yellow Hat” the brim acts like a shallow dome that crowns the figure with a solar disc. Its interior plane is modeled by temperature rather than shadow—cooler where lilac-glazed grays temper the yellow, warmer near the rim where ochre thickens. The brim’s asymmetrical swell keeps the form alert, echoing the slight tilt of the sitter’s head and the diagonal of the trim below. Because the hat borrows yellow from the background, figure and ground interpenetrate: the sitter is both in the room’s light and the source of it. This fusion heightens the icon-like effect without sacrificing the portrait’s humanity.

Light, Shadow, And Mediterranean Diffusion

The picture is lit by diffused, ambient light rather than a single directional beam. Value contrasts are compressed so that color and line can shoulder descriptive duty. Shadows read as coolings rather than darkenings: lavender gathers under the brim, at the side of the nose, and beneath the arms, while warm reflections bloom along the hat’s lower edge and the coat’s lapels. Small, opaque highlights—on the beaded trim and the tiny flower—are rationed so that nothing sparkles at the expense of the whole. This restraint makes the “pearl” effect of the flesh believable: the skin seems to glow from within, thanks to thin layers that let underpainting breathe.

Space, Depth, And Productive Flatness

Depth is intentionally shallow. The background is a large color plane broken only by a faint vertical at left and a cooler zone at right that keeps the yellow from becoming monotone. The sitter presses forward, almost flush with the surface. Overlap—the hat against the ground, the arms crossing the torso—is enough to persuade space without surrendering the primacy of the plane. This productive flatness echoes the logic of Matisse’s Nice interiors and anticipates the decisive interlocking shapes of the late cut-outs. The painting is not a window; it is a constructed surface where relations can be seen all at once.

Psychological Temperature And The Poise Of The Sitter

Although Matisse famously insisted that painting should provide “a soothing, calming influence,” this portrait achieves calm without blandness. The sitter’s crossed arms introduce a guarded poise, but the face—open, direct, and quietly alert—modulates any hardness. The hat, a theatrical object, is handled with such structural clarity that it never dominates the person beneath. The portrait suggests presence rather than personality: here is a figure brought into balance with the world around her, her dignity measured not by expression but by the equity of the painting’s parts.

Rhythm, Music, And The Time Of Looking

Matisse arranges visual intervals like a composer spaces notes. The yellow field sustains a long, luminous chord; the violet coat provides a counter-chord in a cooler key; the white trim ticks along like a slow ostinato; the flower offers a brief grace note; the face supplies the melody—spare, memorable, and centered exactly where the two main chords meet. The eye moves in a repeating circuit: brim to flower, down the beadwork to the crossed arms, back up the lapel to the mouth and eyes, then outward to the yellow that holds everything in a single breath. The painting does not require decoding; it rewards attentive pacing.

Material Touch And The Differentiation Of Surfaces

Matisse differentiates materials through tailored handling rather than descriptive detail. The hat’s surface is brushed in broad, semi-opaque passes that leave faint tracks, appropriate to felt or straw under bright light. The violet coat is painted more densely, the pigment slightly dragged to suggest cloth that absorbs light rather than reflects it. The trim is laid on in small, impasto points that catch the eye like stitched pearls. Flesh is thinned out, glazed, and allowed to mingle with the ground so the head feels lit from within. The result is tactile variety without illusionism, convincing precisely because it stays faithful to the plane of paint.

Dialogues Within Matisse’s Oeuvre

“The Yellow Hat” converses with earlier Matisse portraits that stage bold headwear against saturated grounds—most famously “Woman with a Hat” (1905)—but replaces Fauvist volatility with late-1920s poise. It also speaks to the Nice odalisques through its reliance on complementary chords and its belief that pattern regulates emotion. In its simplified ground and decisive silhouette, the portrait foreshadows the cut-outs of the 1940s, where color islands meet along exact seams. Yet it remains stubbornly painterly: the living edge, the breaths of underlayer, and the subtle temperature shifts would be impossible in paper alone.

Evidence Of Process And Earned Equilibrium

The picture’s serenity records a history of decisions. Along the brim, faint earlier positions are visible where yellow meets lilac, proof that Matisse moved the edge to secure a truer arc. The left shoulder shows a restated contour that aligns more convincingly with the coat’s triangular thrust. The beaded trim varies in spacing—a sign that the rhythm was adjusted by eye rather than compass. These pentimenti make the harmony credible; the balance we experience is achieved, not automatic.

Ornament, Identity, And The Ethics Of Looking

Because the hat is so spectacular, the portrait invites reflection on ornament and identity. Matisse refuses caricature: neither the hat nor the trim overwhelms the person. Instead, adornment becomes a means to think about structure, a way to distribute attention fairly across the surface. The sitter is not reduced to a fashion plate; she is the organizing center that makes hat and coat coherent. The ethics here are visual and respectful: pleasure is granted to color, line, and texture without using the figure as a prop.

Why The Painting Endures

“The Yellow Hat” endures because it transforms simple oppositions into sustained cooperation. Warm yellow and cool violet, rigid triangle and pliant oval, decorative trim and architectural field—each retains its character while enabling the others. The face, drawn in the fewest of lines, becomes unforgettable precisely because it is suspended in this balanced system. The portrait offers satisfactions that do not exhaust themselves: the shimmer where lilac cools the hat’s underside, the pulse of white beads along the lapel, the way a single dark stroke sets an eye in its socket, the quiet glow of skin inside a disciplined geometry. It is a lesson in how modern painting can be humane without psychological fuss and decorative without superficiality.

Conclusion

With “The Yellow Hat,” Henri Matisse shows that a portrait can be constructed like a room: founded on planes of color, stabilized by geometry, enlivened by pattern, and made habitable by a breathing edge. The sitter’s presence is not the result of mimetic detail, but the consequence of a carefully tuned climate where yellow radiates, violet steadies, white regulates, and line speaks with authority. The painting models a way of seeing in which clarity is generous and pleasure is rigorous. In its calm, lucid way, it belongs among Matisse’s most persuasive arguments for the intelligence of color.