Image source: wikiart.org

A Modern Landscape Seen Through Glass

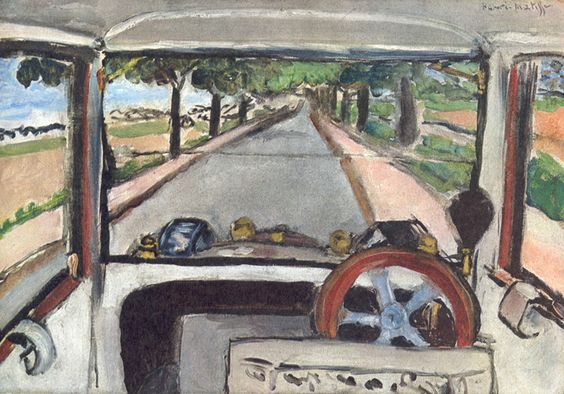

Henri Matisse’s “The Windshield” (1917) stages an encounter between two worlds that rarely meet on equal terms in early twentieth-century painting: the intimate, manufactured space of an automobile and the expansive continuity of the open road. The painting is neither a pure interior nor a pure landscape. It is a hybrid—half cockpit, half avenue—where rectangles of glass parcel out a horizon and the steering wheel’s red-brown circle counters the lane’s razor-straight vanishing point. Matisse turns a drive into a lesson about seeing: every view is framed, every movement is measured by things close at hand.

First Impressions: A Room and a Road at the Same Time

At a glance we sit inside a car looking outward. Pillars at left and right divide the windshield into panes; the dashboard runs like a ledge; the rim of a large wheel enters from the lower right; knobs, mirrors, and a few yellow instrument heads punctuate the midground. Beyond the glass stretches a tree-lined road tapering to a tight point on the horizon, with parallel pinkish verges and fields of green and tan on either side. The effect is startlingly contemporary: a snapshot of modern transport painted with the economy and frankness that mark Matisse’s wartime period.

A Composition Built from Counterforces

The design plays two geometries against one another. The car supplies rectangles and circles. Windows and pillars establish a firm architectural scaffold; the steering wheel, its metal spokes and red-brown rim, offers a counter-rhythm of arcs. The world outside is organized by an urgent triangle: road edges and tree rows race toward a single vanishing point dead ahead. As these forces meet—static frame versus accelerating depth—the painting acquires its tension. We inhabit a stable seat, yet the image vibrates with implied motion.

The Windshield as a Picture-Within-a-Picture

Matisse’s long fascination with windows—think of the interiors and balconies of 1914–1916—finds a new, mobile avatar here. The windshield behaves like a museum wall cut into three paintings: left sliver of landscape, central avenue, right sliver with trunk and verge. The division is functional in a car, but pictorially it does something profound. It reminds us that seeing is always mediated by a frame, whether carved wood, cut glass, or the very edges of a canvas. “The Windshield” is therefore self-reflective without being coy; it is a painting about looking in the act of looking.

The Central Axis and the Vanishing Point

Matisse places the vanishing point high and centered, a choice that flattens the near ground slightly while thrusting depth into the upper third. This keeps the viewer’s attention inside the car as much as beyond it: the foreground ledge, with its shallow curve and instrument bumps, retains real pictorial weight. The road reads as inevitable—one line stemming from two rails—yet it is the world inside the glass that tempers the rush forward and anchors the scene in present tense.

Color and Climate: A Cool, Breathable Light

The palette is austere and purposeful. Grays and blue-grays dominate the interior, cooling metal and glass without fetishizing reflections. Outside, greens of trees and fields alternate with warm earth and salmon-pink verges, creating a late-afternoon climate that never turns theatrical. The steering wheel’s red-brown is the warmest chord, a contained accent that keeps the lower right alive. Because colors are subdued, relations do the expressive work: cool interior against temperate landscape; gray air against warmer earth; a sober cockpit holding a hopeful horizon.

Black Contour as the Painting’s Carpentry

By 1917 Matisse had reintroduced black as a constructive color. Here, black strokes structure the pillars, indicate rubber seals along the panes, and define the steering wheel’s circumference with an authority that keeps the form loud but not shouty. In the landscape beyond, darks run through tree trunks and shadows, yet they never intrude. The black is elastic—thickening and thinning with pressure—and because of that elasticity it behaves like ironwork: strong enough to hold the composition, supple enough to admit light.

Brushwork and the Truth of the Surface

The paint sits frankly on the support. The lane’s interior is swept with long, horizontal pulls that suggest a smooth macadam without literal detail. Tree canopies are struck with brisk, leafy swipes that resist fuss. Chrome fittings and small dials on the dash are handled as fat dabs of color rather than miniature illustrations. Everywhere we feel the wrist rather than a hidden technique: the record of driving translated into the record of touch.

Motion Without Blur

Many painters of modern speed resorted to blur and repetition. Matisse achieves motion another way. The converging verges and trees guarantee forward momentum; the large wheel cropped at the right edge implies the driver’s proximity and potential action; the dashboard’s shallow curve suggests the car’s nose slicing the air. Nothing smears. Instead, motion is a condition created by geometry and placement. You, the viewer, complete the drive.

Human Presence Without a Figure

No driver is shown, and yet the painting is saturated with human presence. The wheel is within reach; the chrome knob at left waits for a hand; the thin black stem of a mirror or wiper punctures the right pane. Absence of the body amplifies embodiment. We inhabit the seat and feel the visual task of steering: keep between the pink verges, trust the rows of trees, attend to the shrinking point ahead. The canvas becomes a temporary instrument panel for the eyes.

The Autocar as a New Studio

Matisse had made windows into studios before—his interiors in Paris, his views on the Côte d’Azur. The car extends that idea. It is a mobile room that carries its own frames. In 1917, after years of rail travel and wartime restriction, the automobile promised autonomy and privacy. “The Windshield” records the sensation of making a painting in that moving studio: an open horizon held in a manufactured grip, a modern pastoral experienced through engineered glass.

The Road as Metaphor for Compositional Clarity

The road is compositional destiny made visible. From foreground to distance, lines fuse into a point; no narrative detours are available. That clarity mirrors Matisse’s wartime ethic: reduce the number of elements, let structure do the lifting, and let color function as climate rather than spectacle. The painting’s steady geometry is not an anecdote about travel; it is a manifesto about how to give a viewer stable bearings in a complex world.

Windows Across Matisse’s Oeuvre

Seen alongside “The Window” (1916) or the many Nice-period interiors with balconies, this canvas reads like a cousin—a more utilitarian version of the same insight. Where those rooms use shutters and curtains to orchestrate rectangles, the car offers pillars and panes. Where those scenes hold fruit, fabrics, and figures between viewer and view, this one offers the apparatus of driving. The continuity across subjects is striking: framing devices are never simply architectural; they are compositional tools that teach the eye how to dwell in the image.

The Eye’s Route Through the Image

The painting proposes a satisfying itinerary. Most eyes start at the wheel—red-brown against gray—then step over the dash into the road’s broad plane. They track the pink verges inward, check the tree rows pulsing at either side, then lock onto the tiny slot of sky at the horizon before looping back along the roofline and pillars to the wheel again. Each leg of this route is punctuated by a crisp value or color change—warm against cool, dark frame against open road—so the journey can repeat indefinitely without fatigue.

Light on Glass Without Illusionism

Painting glass invites theatrical tricks. Matisse refuses them. There are no virtuosic reflections of trees in the panes, no hard highlights mimicking sunlight on a windshield. Instead he renders glass as a mild gray air that slightly lifts the value of whatever it covers. The interior and exterior keep their identities, and the viewer experiences the transparency as a fact rather than a demonstration. The restraint makes the scene more credible and the driving more immediate.

Comparisons and Divergences with Contemporary Modernism

In the decade surrounding 1917, the Futurists and some Cubists embraced speed, fracture, and mechanical fetish. Matisse’s answer is gentler and, in its way, bolder. He admits the automobile as subject while preserving the human scale of the gaze. He adopts geometry without sacrificing atmosphere. He lets modernity in through a windshield rather than through an ideology. The present enters the picture not as aggression but as a new kind of stillness: a pause within movement.

Wartime Discipline and Everyday Modern Life

The date anchors the painting in a period when Matisse tightened his palette, used black as structure, and sought images that could offer balance amid upheaval. A roadside avenue—a motif as old as pastoral travel—becomes a modern consolation when filtered through an automobile’s architecture. The windshield turns the landscape into an orderly procession; the steering wheel turns choice into a visible circle. The everyday thus becomes a site of compositional ethics.

Material Particulars that Reward Close Looking

Attentive viewing uncovers practical decisions. The road’s central gray is not monolithic; it shifts toward blue near the top to cool the distance. The pink verges are slashed with rough, quick strokes that let undercolor breathe, keeping the edges alive. The tree masses are not pure green; touches of dark blue and brown give them heft without heaviness. The wheel’s metal spokes carry a cool, bluish light that stabilizes the lower right. Everywhere small adjustments prevent the scene from ossifying into diagram.

Why the Painting Feels Fresh Today

“The Windshield” remains crisp because it gets something about modern perception exactly right. We live behind panes—windscreens, phone screens, laptop glass—yet we yearn for open avenues. Matisse dignifies both conditions. He doesn’t pretend the frame isn’t there, nor does he fetishize it. He uses it to organize experience so that the eye can rest even as the mind feels the pull of distance. In a culture that oscillates between distraction and speed, such steadiness reads as newly radical.

A Closing Reflection on Framing and Freedom

Standing before this canvas, one senses a generous proposition. Freedom is not the absence of frames; it is the right frames placed in the right relation to desire. The pillars give order, the wheel gives agency, the road gives direction, and the trees give a rhythm by which to measure time. Matisse aligns these elements so gracefully that the ordinary act of looking through a windshield becomes a demonstration of how to inhabit the modern world: alert, composed, and open to the horizon.