Image source: wikiart.org

Historical Context And The Theatrical Turn In Nice

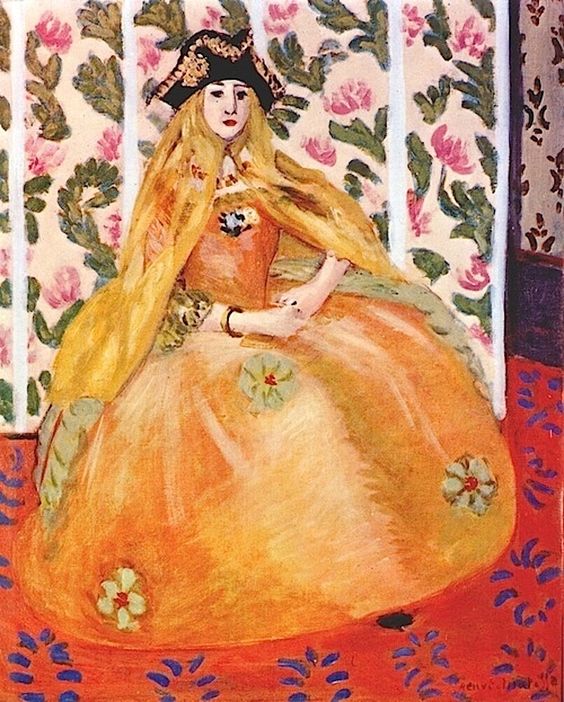

Henri Matisse painted “The Venetian” in 1922 during his Nice period, when interiors, patterned screens, and staged costumes became a flexible theater for color and form. After the upheaval of the 1910s he pursued a calmer intensity: instead of chasing shock, he orchestrated rooms where light, textiles, and the human figure could breathe. This canvas adopts the language of costume—not to mimic historical Venice with antiquarian accuracy, but to test how a ceremonial dress, simplified to essential shapes, could anchor a modern composition. The Venetian theme granted Matisse access to fanlike skirts, mantles, and a tricorn-like hat whose silhouettes read powerfully at a distance. Within that stage he refined his mature ideas: large planes tuned in temperature, calligraphic drawing, and ornament used as structure rather than accessory.

Composition As A Seated Constellation Of Planes

The painting is built around a monumental seated figure whose bell-shaped skirt occupies nearly the entire lower half of the canvas. That orange-gold dome functions like a glowing stage, pushing outward against the patterned floor while compressing space so that figure and room share a shallow plane. Above the skirt, the torso narrows into a corselet of warmer orange; a mantle of pale saffron drapes from the shoulders, creating soft triangles that guide the eye to the face. The background is divided into vertical stripes of floral patterning and pale panels, an interior architecture that steadies the composition like pilasters. The figure sits frontally yet relaxed, hands folded at the center—an anchoring gesture that keeps the expansive costume from overwhelming the person. Everything revolves around the meeting of three simple masses: dome, triangle, and oval—skirt, mantle, and face.

Color Chords And The Temperature Of Ceremony

Matisse tunes the palette to a radiant chord—apricot and orange-gold for the dress, cooling greens for appliqué rosettes and sash, saffron for the mantle, and robust reds and blues for the patterned floor. The background flowers are leaf-green and rose-pink on a cream ground, echoing the rosettes on the skirt so that figure and room converse. The only darks are measured: the hat, a small shadow under the skirt’s front edge, and the discreet accents of eyes and bracelet. These dark notes prevent the composition from drifting and pull attention to the face. Instead of brutal complementary contrast, Matisse prefers adjacency: orange melts into apricot, cream skims into pale yellow, green shifts from olive to celadon. The effect is ceremonial without pomp—warmth that glows rather than burns.

Ornament As Architecture, Not Decoration

Pattern saturates the scene: blossoms climb the wall panels; petals scatter across the carpet; four rosettes punctuate the skirt; the hat’s trim and cloak’s edge carry hints of embroidery. Yet ornament never acts as afterthought. The vertical floral panels stabilize the background and, by alternation with pale stripes, frame the figure. The floor pattern provides a rhythmic counterpoint that keeps the broad skirt from feeling inert. Even the rosettes on the gown are structural: they scale the dome, measuring its breadth and marking its rhythm. Matisse demonstrates how pattern can shape space, calibrate weight, and lead the eye—architecture built from motif.

Drawing Inside The Paint

The linear drawing is economical and confident. A few calligraphic strokes define the hat’s edge, the contour of the face, and the gentle column of the neck. The hands are indicated with simple arcs and ovals—enough to convey grace without fussy articulation. The gown’s circumference is a supple perimeter that thickens and thins as the brush rides over folds, signaling volume by pressure rather than by modeling. Facial features are gathered into a compact mask: firm brows, triangular nose, small vermilion mouth. The discipline of the line lets the color stay luminous and soft; form arises from color boundaries more than from linear enclosure.

Light As A Soft, Continuous Envelope

The room’s illumination is even, like coastal daylight filtered through curtains—the sort of Nice light Matisse loved. Highlights are modest: a pale glint at the cheek, a sheen across the mantle’s fold, a gentle flare on the skirt’s crest. Shadows remain colored rather than black; the underside of the skirt deepens into wine-red, the hat gains volume with a cool violet notch. This soft envelope prevents theatrics. It allows color to carry emotion while preserving the serenity that defines the artist’s mature interiors.

The Face As Calm Authority

Within the riot of textiles, the face holds calm authority. Its oval sits beneath the dark hat like a cameo, framed by long, fair hair that descends to the mantle. The expression is poised and direct—neither coy nor severe. Matisse avoids intricate likeness; he pursues character: a modern sitter bearing an imagined Venetian costume with quiet self-possession. The red of the mouth and the subtle rose at the cheek link the head chromatically to the carpet and wall flowers. The gaze anchors the painting’s human dimension amid its ornamental abundance.

Costume As Modern Abstraction

Matisse’s Venice is not a documentary Venice. The tricorn-shaped hat and voluminous skirt are signs—clear silhouettes chosen for pictorial power. The dress behaves like a landscape; its broad color field absorbs light and reflects nearby hues, while its rosettes act as islets. The mantle drapes like a barrier reef around the face, slowing the eye’s approach and then releasing it toward the central oval. In this way costume becomes abstraction: a set of big, legible shapes that carry feeling through proportion and temperature rather than through historical detail.

Space Constructed By Overlap And Planar Contrast

Depth here is shallow by design. The skirt overlaps the floor pattern, pushing forward; the figure overlaps the wall panels, which step back through pale intervals between floral bands. The carpet’s red key warms the lower plane; the wall’s cream cools the upper plane. These shifts construct space by plane rather than by measured perspective, a hallmark of Matisse’s modernism. The viewer occupies a position close enough to feel the textures yet far enough to see the grand order of shapes.

Rhythm, Repetition, And Visual Music

Repetition organizes the canvas like music. Rosettes on the gown repeat with variation; blossoms on the wall climb in measured columns; the carpet pattern scatters in syncopated beats. Curvilinear forms—skirt hem, mantle edge, hair—play against straight dividers in the background, creating counterpoint. The eye’s path becomes a loop: enter at the bright carpet, rise along the gown to the clasped hands, ascend to the face and hat, descend by the mantle’s edge to a rosette, and return to the floor. Each circuit confirms the picture’s composed tempo—dignified but lively, ceremonial yet human.

Material Presence And Tactile Cues

Although simplified, the painting is tactile. The skirt’s surface is built from soft, scumbled strokes that read as brushed fabric; the mantle’s paint is slightly thicker at folds, catching light like woven wool; the carpet’s pattern is dabbed with brisk pressure to suggest pile. The vase-like corsage at the bodice flashes a compact glitter of darks and lights—a brooch rendered with three or four touches. Such cues keep the sumptuous color grounded in bodily experience.

The Venetian Theme Within Matisse’s Oeuvre

Costume appears often in the Nice interiors—odalisques, Spanish mantillas, theatrical hats—yet “The Venetian” distinguishes itself by the audacity of its single massive shape. Many related works include windows, tables, or musical instruments that share protagonism; here the dress is the stage. The canvas sits at a pivot between earlier Fauvist daring and later clarity. It preserves the joy of saturated color while disciplining it into coherent planes, anticipating the large, clean shapes of the 1930s drawings and late cut-outs.

Psychology Of Ceremony And Poise

The painting’s mood is festive without noise. Ceremony here is an interior state: composure, slow breath, an awareness of being seen. The sitter’s folded hands express self-containment; the mantle gathers the figure; the hat crowns without aggrandizing. This modesty is crucial to the work’s modernity. It doesn’t reenact pageantry; it advances a contemporary idea of dignity, in which person and pattern, self and room, are held in equilibrium.

The Intelligence Of Omission

Wherever detail would drain energy, Matisse omits. There are no lace threads counted, no jewelry faceted stone by stone, no wall molding precisely carved. A few strokes conjure embroidery, another few suggest the hat’s trim. The floor’s blue leaf-shapes alternate at an intuitive pace rather than a mechanical grid. These omissions keep attention on what matters: the proportions of planes, the dialogue of warm and cool, the rhythm of repeats. The eye is free to rest without being burdened by inventory.

The Viewer’s Path And The Experience Of Time

This canvas elongates time through sustained looking. First comes the shock of the orange dome, then the discovery of green rosettes, then the recognition of the wall’s vertical framework, and finally the engagement with the face. With each return lap, the mantle’s temperature shifts and the carpet’s syncopations become more audible. The painting rewards duration, which is exactly the experience Matisse sought to offer in his Nice period: a calm that doesn’t fade with familiarity, because it is built from relations that continue to unfold.

Dialogue With Venice And With Modern Life

While the title gestures to Venice—the city of masks, silk, and ceremony—the painting is rooted in the modern studio. Patterned panels stand in for palazzo walls; a carpet substitutes for mosaic floors. Matisse absorbs the romance of Venice but translates it into a language of lucid planes and breathable light. In doing so he proposes that historical richness can live inside modern clarity. The past is not reenacted; it is distilled into shapes and temperatures that still feel immediate.

Emotional Weather And Lasting Resonance

The emotional key is sanguine composure. Warm oranges and reds generate cheer; cool greens and creams temper them; the dark hat and tiny shadow under the hem introduce just enough gravity to keep the picture from floating. This poised weather explains the painting’s longevity. It models a generous way to stage a person—surrounded by beauty, integrated with pattern, dignified by stillness—without sacrificing modern directness.

Conclusion: Ceremony Reduced To Color And Form

“The Venetian” condenses Matisse’s mature ambitions into a single, memorable silhouette. A seated figure becomes architecture; costume becomes a field for color logic; ornament scaffolds space; and light arrives as a soft, continuous veil. The painting is neither history painting nor portrait alone; it is a clear demonstration that ceremony can be carried by relations of hue, plane, and rhythm. In this room, the past glows through the present, and the present learns how to be luminous without astonishment.