Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction to “The Triumphal Car of Kallo (Sketch)”

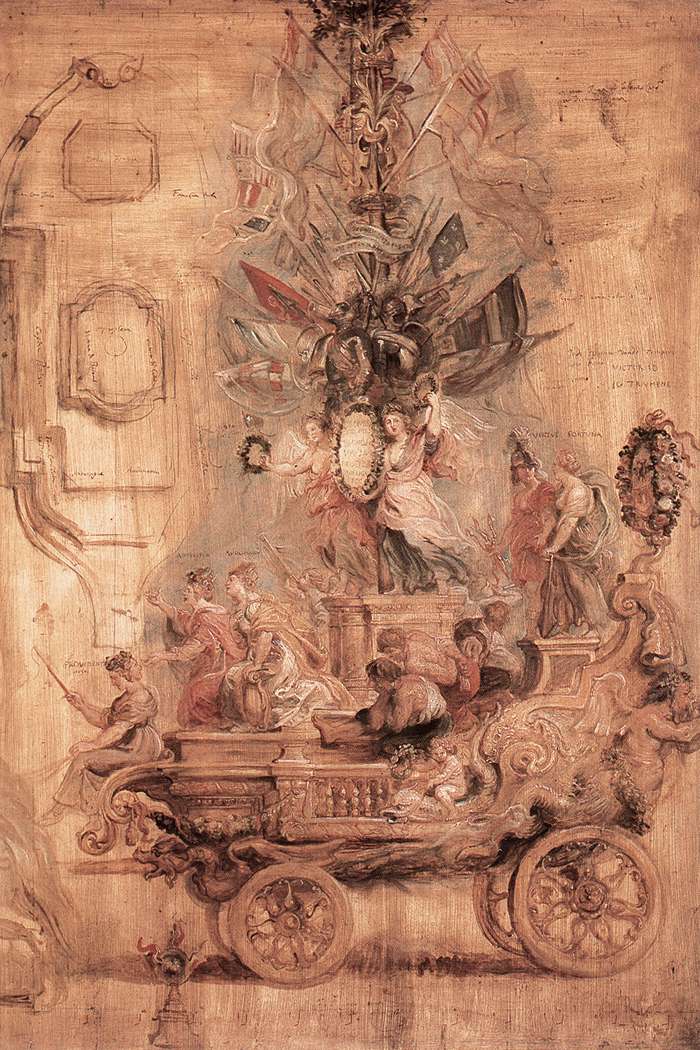

“The Triumphal Car of Kallo (sketch)” from 1638 shows Peter Paul Rubens working at full speed as designer, decorator, and storyteller. Rather than a polished easel painting, this is an oil sketch that lays out a spectacular ceremonial float: a richly carved car on heavy wheels, loaded with allegorical figures, emblems, and trophies of war. Rising above them is a forest of standards, banners, and weapons crowned by a central cartouche.

The sketch was created in connection with festivities celebrating the Spanish victory at the battle of Kallo near Antwerp in 1638. Rubens, by then the pre-eminent artist of the Southern Netherlands, was often called upon to design temporary decorations for civic triumphs, royal entries, and public processions. Here he invents a triumphal vehicle that could roll through the streets, turning recent military events into a grand allegory of victory, peace, and prosperity. The sheet lets us watch him think visually: blocking out architecture, arranging personifications, and testing how they could be read by spectators watching from the ground.

Historical Context and Purpose of the Design

The battle of Kallo, fought in 1638 during the Eighty Years’ War, was a rare and celebrated victory for Spanish forces defending the Catholic Southern Netherlands against the Dutch Republic. Antwerp, a major city under Spanish control, had suffered economically and psychologically from decades of conflict. A victory so close to home demanded public celebration, and Rubens, already famous for his diplomatic work and his allegorical cycles for royal patrons, was the obvious choice to devise visual spectacles.

This sketch belongs to the world of festival culture: ephemeral arches, decorated barges, firework displays, and procession floats that transformed city streets into theatrical stages. Rubens’s task was not only to glorify the military success but also to deliver a message of civic pride and divine favor. The “Triumphal Car of Kallo” would have rolled in a procession, surrounded by music, banners, and crowds. The imagery had to be legible at a distance, combining eye-catching ornament with clear symbolic meaning.

As a sketch, the work functions as a proposal or modello. Patrons and city officials could examine it, approve the program, and then craftsmen, sculptors, and painters would translate the design into a three-dimensional structure and painted surfaces. The quick, fluid handling suggests Rubens was thinking about movement and overall effect rather than minute detail.

General Composition and Structure of the Car

Rubens builds the composition vertically as well as horizontally. At the bottom sits the heavy car, a rolling platform resting on large wheels with carved spokes. The undercarriage is alive with baroque scrolls, masks, and vegetal motifs, giving the impression that the entire vehicle is a moving piece of sculpture. Putti cling to the sides, while garlands and decorative elements spill over the edges.

Above this base, a stepped architectural structure supports a cluster of seated and standing figures. The car is conceived almost like a mobile altar or stage, with multiple levels. Figures at the front and sides lean outward, engaging the crowd that would line the streets. The central zone is occupied by personifications: women draped in flowing garments, a few male figures, and children who assist them. Their poses are theatrical but carefully arranged so that no important figure is completely obscured from any one viewpoint.

The composition then thrusts upward into a tall, tapering mass of military trophies. Shields, lances, drums, helmets, and standards fan out behind a central cartouche, crowned by a flourish of foliage and possibly a heraldic emblem. This vertical axis transforms the car into a monument to martial success, its message legible from afar. The whole design reads as a pyramid of victory: at the base, the earthly vehicle; in the middle, the virtues; at the top, the triumphal spoils of war.

Allegorical Figures and Their Meanings

Even in sketch form, Rubens populates the car with carefully chosen personifications that encode the political message of the project. Many figures carry attributes that reveal their identities, even if inscriptions are only faintly suggested.

At the front of the car, seated on the left, a woman with a staff may represent Fame or perhaps History, recording the deeds of the victors. Beside her, another female figure with flowing drapery and a cornucopia implies Abundance, a promise that peace and victory will restore prosperity to the region. These front-most figures are those the public would see first, welcoming viewers into the symbolic narrative.

Near the center, on a higher level, stands a commanding figure holding a wreath and gesturing toward a central shield or inscription. She likely personifies Victory herself, crowning the exploits at Kallo. Around her, companions carry laurel wreaths and palm branches—traditional emblems of triumph. Some kneel or point toward the text panel, emphasizing that the written record of the victory is as important as the spectacle.

On the right side of the car, another cluster of allegorical women interacts with a garlanded architecture. They may represent virtues such as Fortitude, Prudence, and Constancy. Their gestures—supporting the structure, offering wreaths, or leaning towards one another—suggest that these virtues cooperate to uphold the state.

Below, at the wheels and edges, numerous putti assist in drawing the car or handling symbolic objects. They lighten the mood and connect the lofty personifications with the playful language of festival imagery.

The Trophy Pyramid: Flags, Weapons, and Heraldry

The most visually striking element of the design is the explosion of flags and armor rising above the figures. Rubens gathers the spoils of war into a dynamic trophy: banners billow, lances crisscross, and shields overlap in a dense fan. At the base of this trophy, two or more suits of armor loom, perhaps meant as captured enemy equipment or as generic emblems of martial prowess.

At the center of this cluster sits an oval cartouche. In the sketch it appears lightly colored and framed by foliage, left blank or only loosely inscribed. In the realized car, this space would likely contain a dedicatory text, a motto, or perhaps the coat of arms of the Spanish monarchy or of Antwerp. The upward sweep of weapons directs the viewer’s eye to this central emblem, making it the visual focus of the upper half of the design.

The mass of flags also functions to unite the car’s earthly, architectural base with the open sky of the festival route. As the float rolled through the streets, the fabric standards would catch wind, echoing the painted motion Rubens suggests with loose strokes. The design thus anticipates the actual experience of spectators, fusing painted illusion and real movement.

The Sketch as Working Drawing

One of the great pleasures of this work is seeing Rubens in the act of designing. The panel is full of construction lines, marginal notes, and unrefined passages. Architectural elements on the left and right are only loosely indicated; some mouldings and blank panels show that he was coordinating the car with the façade or stage setting behind it. In places, he scratches out or revises earlier ideas, leaving traces of the decision-making process.

The figures themselves are painted rapidly with fluid, broken brushstrokes. Rather than carefully modeling each face, Rubens suggests heads with a few touches of light and shadow. Only the main personifications receive slightly more definition, enough that their poses and attributes can be read. This economy indicates that the sketch was meant for informed viewers—patrons, assistants, carpenters—who could extrapolate details from the overall conception.

Color is used sparingly but strategically. Warm ochres and reddish tones define the car and figures, while pale whites highlight garments and banners. The ground tone of the panel shows through in many areas, lending the image a unified warmth. This restricted palette allowed Rubens to work quickly while still conveying the optical impact of the eventual decoration.

Baroque Movement and Theatricality

Even in this embryonic state, the design is intensely Baroque. Movement courses through the composition: figures twist and lean, draperies flutter, flags whip in implied wind. Nothing is static. The car seems to surge forward even though we see it from the side.

Rubens orchestrates this dynamism using diagonals and curves. The line of the car’s chassis sweeps upward toward the right, where the ornamental back rises like a wave. The figures’ gestures echo these arcs—arms raised diagonally, bodies leaning into curves. The trophy pyramid shoots straight up, but within it, banners ripple in different directions, preventing the vertical axis from feeling rigid.

This theatrical energy was essential for a processional vehicle. Spectators would see the car for only a brief moment as it rolled past. The design therefore needs to communicate its message instantly through dramatic silhouettes, bold gestures, and clear emblematic clusters. Rubens’s sketch captures that sense of fleeting impact: it almost vibrates with imagined fanfare, trumpets, and cheering crowds.

Symbolic Program: War, Peace, and Civic Pride

The Triumphal Car does more than celebrate military victory; it weaves a narrative about the relationship between war and peace, conflict and prosperity. The trophies of weapons and armor testify to the reality of battle, but they are subordinated to the allegorical figures of Victory, Abundance, and the civic virtues. War is presented as a means to an end—the defense of the city and the restoration of flourishing life.

The presence of female personifications softens the message, framing victory not simply as brute force but as something blessed by virtues and the arts. Some figures appear to be playing instruments or carrying writing tablets, showing that music and learning also participate in the triumph. For a cultured audience in Antwerp, this would signal that their city’s identity encompassed commerce, art, and scholarship as well as military strength.

The car can thus be read as a moving manifesto for the city and for the Spanish Habsburg authorities: they are protectors, guarantors of peace whose victories will yield prosperity. In a period of long, exhausting war, such a message was politically vital.

Rubens as Designer of Spectacle

This sketch is a reminder that Rubens was not only a painter of canvases but a versatile designer who created tapestries, book illustrations, and festival decorations. His ability to think in three dimensions and to translate complex symbolism into easily readable imagery made him invaluable to rulers and city councils.

In the “Triumphal Car of Kallo,” we see him bringing together multiple skills. His knowledge of classical iconography informs the choice of allegories; his painter’s eye orchestrates light and color; his sense of architecture shapes the form of the car. At the same time, he is attentive to practical concerns: where the wheels must go, how the figures might be constructed, and how the design would look from street level.

This dual role—artist and stage director—places Rubens at the heart of Baroque culture, where art often spilled out of galleries into public space. The sketch stands as a rare surviving trace of a spectacle that would otherwise be lost to time.

Painterly Surface and the Appeal of the Sketch

For modern viewers, part of the appeal of this work lies precisely in its unfinished, sketchy nature. The visible brushwork, exposed ground, and partial indications give the painting a freshness that fully finished works sometimes lack. We feel close to Rubens’s hand, almost as if watching him paint.

The sketch also invites us to imagine the final car. We can mentally add color to the banners, detail to the faces, and carved depth to the scrollwork. This imaginative participation allows the viewer to experience something akin to the anticipatory excitement that would have surrounded the actual festival.

Moreover, the looseness of the handling reveals Rubens’s mastery. Even with minimal strokes, he suggests weight, volume, and complex groupings. The car’s wheels feel solid; the figures sit convincingly on their plinths; the entire structure seems plausible as a real object, despite the rapid execution. This ability to evoke solidity with economy is one of Rubens’s great gifts.

Legacy and Interpretation Today

Although the actual triumphal car has long since vanished, this sketch preserves the memory of a specific historical moment and of Rubens’s role in shaping civic identity. It demonstrates how art and politics intertwined in early modern Europe, where victories were celebrated not only with official proclamations but with visual spectacles designed by leading artists.

For art historians, the sketch is a valuable document for understanding Rubens’s working methods, his collaboration with patrons, and his approach to allegorical programs. For general viewers, it offers a glimpse into the festive culture of the Baroque city, where streets could be transformed into temporary theaters of power and pride.

Today, the “Triumphal Car of Kallo (sketch)” can also be appreciated as an autonomous work of art—a concentrated burst of imagination in oils on panel. Its whirling forms, crowded figures, and soaring trophies encapsulate the exuberant spirit of Rubens’s late style and invite us to reflect on how societies commemorate conflict and dream of peace.