Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

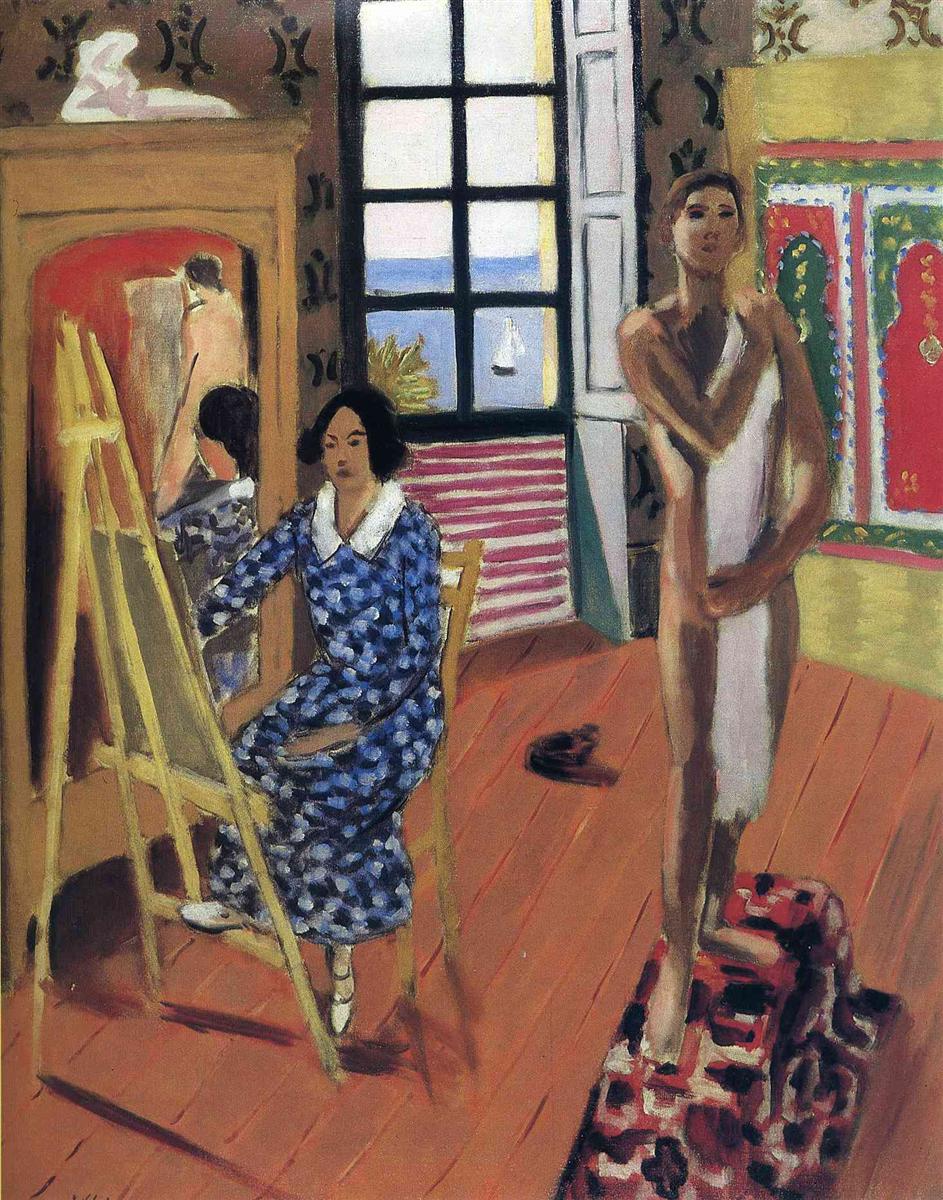

Henri Matisse’s “The Three O’Clock Sitting” (1924) is a luminous studio drama in which the quiet rituals of making art become the true subject. A model stands on a patterned rug at right, a painter in a blue dress works at the easel at left, and between them a gridded window opens to the Mediterranean where a small sail slips across the horizon above red-and-white awning stripes. A mirror behind the easel doubles the scene, capturing the painter and the nude from another angle. The result is not an anecdote about a particular afternoon but a composed meditation on looking, reflection, and the disciplined calm of the studio—an environment Matisse tunes with pattern, color, and ambient light until every surface feels equally alive.

The Nice Period Studio and Its Vocabulary

By 1924 Matisse had settled into his Nice period, exchanging the high-voltage clashes of Fauvism for a modern classicism based on even light, shallow layered space, and what he called a “democracy of surfaces.” Interiors became laboratories for this language. He staged textiles, screens, rugs, musical instruments, flowers, and models in rooms that breathed Mediterranean air. “The Three O’Clock Sitting” gathers the full vocabulary: an open window framing sea and sky, a patterned wall pressed forward like a tapestry, a small carpet under the model’s feet, and a mirror that folds the studio back on itself. The hour in the title implies routine. This is not spectacle but schedule—the day’s appointed session when attention, not drama, is paramount.

Composition as a Theater of Relations

Matisse divides the canvas into three interlocking blocks. On the left, the easel, mirror, and painter create a warm pocket of ochres, browns, and blues. In the center, the large gridded window establishes a cool reservoir of light and a stable geometry that calms the room. On the right, the standing model shares space with a red-and-green screen, a golden wall, and a soft wedge of floor. This tripartite structure allows the eye to move in phrases: from the painter’s bent figure to the window’s grid, from the grid to the model’s vertical body, and back again along the awning stripes to the painter. The floorboards run diagonally toward the right, accelerating the gaze to the model while the rug under her feet acts as a brake, holding the figure in place.

The Mirror’s Double and the Act of Looking

The mirror behind the easel is central to the painting’s meaning. It repeats the painter’s head and shoulders and shows the model’s back, compressing three vantage points—painter, model, viewer—onto a single plane. This device lets Matisse avoid heavy modeling while asserting presence: the painter exists as both active worker and reflected witness; the model is both a living person and an image in the painter’s field. The mirror also keeps the space shallow, denying deep recession and reminding us that painting is a flat orchestration of shapes and intervals. What we see is not the illusion of a room but a set of relationships tuned until they hum.

Color Climate: Warm Work, Cool Air

Color carries the painting’s atmosphere. The studio half-tones—ochre floorboards, tobacco mantle, warm tans of the nude—belong to a sunlit interior. Against them Matisse places sustained cools: the blue sea visible through the window, the cobalt and navy daubs on the painter’s dress, and the gray-lavender shutters that temper the light. The red-and-white awning injects a stable rhythm of stripes that bridges warm and cool, echoing the floor’s directional energy while feeding the center of the composition with low, steady beats. Patches of saturated red in the screen at right answer the awning and the small rug, welding the picture’s warm notes into a chord that never overwhelms the calm blues.

Pattern as Architecture

Pattern in Matisse is structural, not decorative, and here it is everywhere. The painter’s dress is a spray of daubs that makes her a mobile field against the solid easel. The wall motifs—dark, leaflike stamps on a lighter ground—float forward, flattening the room into a tapestry. The model’s rug is a concentrated cluster of rounded forms; it grounds her body and repeats the screen’s ornamental logic on a smaller scale. Even the awning stripes function as architecture: their horizontals stabilize the window’s grid and keep the central panel from becoming a mute block of color. Each motif sets a different tempo, and together they pace the eye without clutter.

The Model: Column of Warm Light

The model stands tall, slightly angled, a white cloth trailing from one hand across the torso. Matisse resists anatomical fuss; he builds the figure from large warm planes, letting a few decisive shadows state the turn of hip and ribcage. The face is abbreviated, the gaze directed inward, the stance serene rather than theatrical. Placed on the small red rug, she is a column of warm light rising within the studio’s measured order. Her verticality answers the window’s mullions and the easel’s legs, while her flesh tones bind the carpet and golden wall into the living presence of a person.

The Painter: Concentrated Poise

At the easel sits a woman in a blue patterned dress with a crisp white collar, one foot tucked behind the other, hands poised to paint. She is rendered with the same economy that shapes the model: broad volumes clarified by a few lines. The pattern of her dress animates her otherwise compact posture, and her profile connects us to the mirror’s back-of-head reflection—two positions in the same moment of concentration. Matisse shows no brush or palette; the act of painting is suggested by posture and attention rather than by props.

Space by Layers, Not Vanishing Points

Depth is achieved by overlap and temperature rather than linear perspective. Foreground: the floorboards and rug. Middle: model, painter, easel, mantle. Rear: mirror and window. Farthest: the sea and sky band. The intervals between layers are short, placing the viewer close to the action. The window keeps the composition breathable; its external blue gives the studio a cool reservoir that prevents the warm interior from feeling airless. This stacked arrangement is one reason Matisse’s interiors feel serene: there is no rush toward vanishing points, only a balanced sequence of planes.

Light Without Theatrics

The light is the Nice period’s signature: ambient, generous, and non-dramatic. It pools evenly on the floorboards, softens the model’s flesh, and glances off the mantle without throwing hard shadows across faces. Highlights are milky—a gleam on the collar, a shallow sheen on shoulders—while darker notes are warm and colored, never dead black. This steady illumination lowers the emotional temperature and allows color and rhythm to carry expression.

Rhythm, Interval, and the Music of Looking

The painting is engineered like a slow, assured piece of chamber music. Long notes: the window’s grid, the tall wall, the expanse of floor. Middle beats: the awning stripes, the screen panels, the easel’s legs. Quick notes: the small sail on the sea, the rug’s red spots, the painter’s white collar and shoes. The viewer’s path follows a phrase: enter at the easel, pause at the painter’s head, slip to the mirror and glimpse the second viewpoint, drift into the window’s cools and sail, return along the awning stripes to the model’s warm vertical, land on the rug’s red percussion, and glide back across the floor to the easel again. Each circuit clarifies how poised the relations are—no one element stresses the others.

The Screen and Mantle: Tuning the Edges

At the far right stands a red and green screen whose trimmed panels carry small dotted ornaments. It prevents the golden wall from becoming monotonous and contributes a saturated warm accent that balances the cooler left half. The mantle at left, with a small reclining sculpture on its shelf, echoes the easel’s ochres and anchors the painting with a block of interior architecture. These two vertical masses—mantle and screen—work like bookends. They keep the lateral energy in check and hold the window and figures in a coherent field.

The Studio as Subject

While the painting includes a model, it is not chiefly a figure painting; it is a portrait of a working studio and of the rituals that happen there every afternoon at three. Tools, surfaces, and light share the stage with people. The nude is a presence among presences, not the singular focus of desire. This is consistent with Matisse’s larger ethic in Nice: painting is a craft practiced inside a tuned environment where attention can rest. By presenting the painter and model with equal calm, he lifts both from anecdote into archetype.

Dialogues Within Matisse’s Oeuvre

“The Three O’Clock Sitting” speaks to several neighboring works. It shares the window-and-awning motif with the “Young Woman Playing Violin” interiors, the patterned screens of the odalisque pictures, and the mirrored doubling found in portraits like “Standing Odalisque Reflected in a Mirror.” But here those devices serve a different end: instead of sensual languor or musical reverie, we witness visual labor. The painting draws a quiet line from the 1908 “Red Studio” to Nice: the studio is still a kingdom of art objects and patterns, but now filled with benevolent light and a human rhythm marked by the clock.

Material Presence and Brushwork

Even in reproduction the surface reveals Matisse’s touch. The floorboards are pulled with long, elastic strokes that leave faint ridges; the dress pattern is dabbed wet into wet so some spots bloom softly; the window grid is laid with firm, slightly wavering lines that keep it human; the rug’s dark shapes are thick, sticky notes against the smoother ground. The mirror’s interior is scumbled and warm, turning the mantle recess into a glowing pocket. These varied pressures make the studio feel tactile—an environment made through gestures, not manufactured.

Meaning Through Design

What, finally, does the painting propose? That clarity is the studio’s highest luxury. A routine hour, familiar objects, and ordinary coastal light can yield a world of poise when relations are exact. Warm and cool hold each other; pattern and plain alternate; reflection and direct sight cooperate. The model’s calm and the painter’s focus are two faces of the same discipline. Matisse offers a lesson more than a scene: create spaces where attention thrives and images will follow.

How to Look, Slowly

Start with the painter’s white collar and count a few blue daubs as if they were beats. Step into the mirror and hold both perspectives—the painter as worker, the model as reflected. Slide to the window’s blue band and the tiny sail, then return along the awning’s stripes to land on the model’s shoulder and the white cloth crossing it. Drop to the small rug and feel its red percussion, then drift across the floorboards back to the easel. Repeat the path. Each pass deepens the sense that the picture is a rhythm rather than a narrative.

Conclusion

“The Three O’Clock Sitting” is a crystalline statement of Matisse’s Nice-period mastery. Its studio is a theater of measured light and tuned relations; its figures are dignified by poise rather than drama; its mirror and window fold inside and outside into one breathable surface. The painting’s calm is not passivity but concentration—the kind that allows color and pattern to carry feeling without agitation. Nearly a century later, it remains persuasive because it shows the daily, repeatable grace at the heart of making art.