Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction to “The Three Graces”

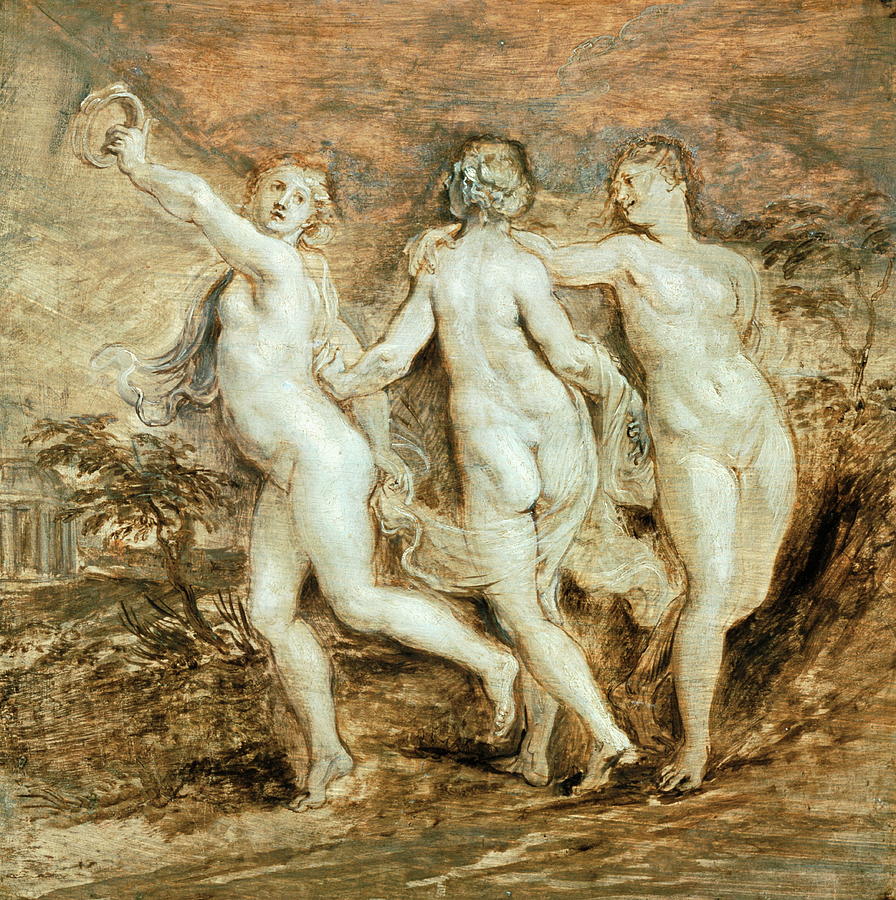

Peter Paul Rubens’s “The Three Graces” exists in several versions, and this particular work is a lively sketch that reveals the artist’s creative process at its most spontaneous. Three nude female figures move together across an earthy landscape, their bodies intertwined in a rhythm of steps and glances. Unlike the highly polished finished canvas, this study retains an open, almost unfinished quality: the ground color shows through, brushstrokes are visible, and much of the background is suggested rather than fully defined.

Even in this preparatory state, the painting captures the essence of Rubens’s vision of the Graces as embodiments of sensual beauty, friendship, and harmonious movement. The sketch allows viewers to watch Rubens thinking in paint, shaping the composition, testing poses, and choreographing the dance of three bodies that would become one of his most celebrated classical themes.

Mythological Background And Meaning Of The Graces

The Three Graces, or Charites, come from Greco-Roman mythology. Traditionally named Aglaia, Euphrosyne, and Thalia, they personify charm, joy, and abundance. In ancient art and literature they are companions of Aphrodite or Venus, goddesses of beauty and love, and they represent the gifts of grace that flow from the gods to humanity and back again in a cycle of generosity.

Renaissance and Baroque artists loved the subject because it provided an elegant justification for painting three female nudes together while also conveying an ideal of refined sociability and harmony. Rubens, steeped in humanist culture and familiar with antique sculpture, adopts the motif but infuses it with his distinctive Northern sensuality. His Graces are not distant marble goddesses; they are warm, fleshy, and alive, celebrating the pleasures of movement and companionship.

Composition And The Dance Of The Bodies

The composition forms a loosely spinning circle. The central figure, seen from the back, anchors the group. Her weight rests on one leg while the other steps forward, suggesting motion. Her arms extend outward to link her to her companions: one hand on the shoulder of the figure to the left, the other lightly touching the arm of the figure on the right.

The figure on the left strides forward, torso turning toward the viewer, head thrown back. Her raised arm holds a wreath or tambourine-like object aloft, intensifying the sense of festive motion. The figure on the right turns inward, her head inclined toward the central Grace as if engaged in conversation. Collectively, they form a swirling chain of bodies that seems to move across the picture plane like a dance.

Rubens uses the diagonal thrust of their legs and the counter-curving torsos to generate vitality. The composition is both balanced and dynamic; no single figure dominates, but the eye continually circulates among them. The central back-turned figure offers a sculptural view of the body, while the flanking Graces provide more frontal and three-quarter views. This variety allows Rubens to display his mastery of anatomy from multiple angles within a single group.

The Sketch-Like Quality And Rubens’s Working Method

This version of “The Three Graces” is not a fully finished painting but an oil sketch, often called a modello. Rubens frequently prepared such sketches on panel to experiment with ideas before executing large canvases or to present designs to patrons. In this work, the brushstrokes remain loose and visible; the brown underpainting of the ground shines through in many areas, particularly in the landscape and sky.

The figures are more developed than the surroundings, suggesting that Rubens’s main concern was the interplay of bodies and gestures. He models the flesh with broader, more gestural strokes than in his finished works, suggesting volume through quick sweeps of pale paint over darker underlayers. Drapery and details are implied with a few lines rather than carefully rendered folds.

This openness gives the painting a vibrant, almost modern energy. Viewers can sense the speed and confidence of Rubens’s hand as he lays in the forms, corrects them, and strengthens contours. The sketch shows how composition and movement came first; refined surface and polished detail would come later, if the idea proceeded to a grander canvas.

Light, Color, And The Warm Flesh Tones

Even in the sketch form, Rubens’s sensitivity to light and color is evident. The palette is relatively limited, dominated by warm earth tones, creamy whites, and pale highlights, with touches of cooler gray in the sky. The figures’ bodies are painted with warm, luminous flesh tones that stand out against the more muted landscape. This contrast pushes them forward in space and emphasizes their sensual presence.

Light falls from the upper left, catching the shoulders, backs, and flanks of the Graces. Highlights appear on the raised arm of the left-hand figure, the spine and buttocks of the central figure, and the hip of the right-hand figure. These gleams of light are not meticulously blended but rather quickly brushed on, yet they convincingly suggest roundness and texture.

The background is painted with thin, transparent layers, allowing the panel’s tone to participate in the overall color scheme. Loose strokes of brown and green indicate trees and ground, while the sky is a wash of ochres and grays. This subdued environment sets off the brightness of the nude bodies and keeps the eye focused on the central trio.

The Landscape And Architectural Hints

Behind the Graces, Rubens suggests a faint architectural structure on the left—perhaps a classical temple or colonnade—nestled among trees. It is little more than a few vertical lines and a hint of a pediment, but its presence quietly establishes a mythological setting. The Graces dance not in an anonymous field but in an Arcadian landscape associated with ancient gods and goddesses.

The low-lying vegetation and sweeping ground line give a sense of place without competing with the figures. The landscape curves gently around them, echoing the sway of their bodies. Rubens uses this environment not to tell a detailed narrative but to create a poetic mood: a timeless grove, lightly touched by human architecture, where divine figures can appear in their natural, unselfconscious state.

Sensuality, Beauty, And The Rubensian Ideal

Rubens is famous for his full-bodied female nudes, and this study epitomizes his particular ideal of beauty. The Graces are robust and fleshy, with rounded thighs, soft bellies, and gently sloping shoulders. Their bodies are not sharply defined by rigid musculature; instead, they appear pliant, living forms that respond to movement and touch.

This sensuality is not purely erotic but connected to ideas of abundance and vitality. The Graces symbolize the overflowing generosity of nature and the gods; their fullness of form visually expresses this concept. Rubens’s brushwork further enhances the sense of living flesh. The quick, swirling strokes mimic the softness and subtle shifts of tone on skin under shifting light.

At the same time, the figures maintain an elegance of proportion and pose. Their gestures are graceful, their heads held high, their movements coordinated. The right-hand Grace’s slight twist at the waist, the central figure’s poised step, and the left-hand figure’s extended arm combine to create an intricate choreography that transcends purely physical description and embodies the harmony associated with divine grace.

Gesture, Expression, And Relationship Between The Figures

Although their faces are not rendered with detailed features in this sketch, the Graces’ expressions and gestures still convey personality and interaction. The left-hand figure looks back over her shoulder toward the viewer, her eyes wide and her mouth slightly parted. This backward glance invites us into the scene, acknowledging our presence while she remains engaged in the dance.

The central figure’s head is turned toward the right-hand Grace, suggesting a quiet conversation or shared moment. Her arm around the latter’s shoulders reinforces a sense of intimacy and mutual support. The right-hand Grace inclines her head toward the center, lips close to her companion’s ear, as if whispering.

These interactions transform the trio from a static allegory into a circle of friends. The Graces do not merely stand together as symbols; they relate to one another as individuals. This warmth and mutual engagement are essential to their meaning as embodiments of generosity, companionship, and social pleasure.

Classical Sources And Artistic Influences

Rubens was an avid student of antiquity and Italian Renaissance art. His concept of the Three Graces draws on classical sculpture and earlier paintings by artists such as Raphael. The familiar arrangement—with one figure seen from behind between two frontally or three-quarter-view figures—appears in ancient reliefs and Renaissance reinterpretations. Rubens adapts this formula but gives it more dynamic motion and robust physicality.

Italian influences are evident in the fluid contour lines and the emphasis on rhythmic movement. Yet the handling of paint—the thick highlights, earthy underpainting, and emphasis on tactile flesh—is very much Rubens’s own. The sketch also reveals his engagement with the Venetian tradition of color and painterly freedom, where forms emerge from layers of brushwork rather than precise drawing alone.

The Sketch As A Window Into Baroque Creativity

Because this work is a preparatory study, it offers insight into Baroque artistic practice more broadly. Oil sketches like this were often used to test compositions, study the play of light on bodies, and explore expressive poses. They were not always intended for public display but for the artist’s own use or for communication with workshop assistants and patrons.

In contrast to later academic traditions that prioritized finish and smooth surfaces, Baroque artists like Rubens valued the expressive power of visible brushwork and rapid execution when planning a design. The energy of the sketch sometimes captures an immediacy that can be softened in the final painting. Today, many viewers find these studies especially compelling because they reveal the artist’s hand and thought process so clearly.

Emotional And Aesthetic Impact On The Viewer

Encountering this version of “The Three Graces,” viewers may feel as though they have stumbled upon an intimate moment in the studio. The unfinished, open quality of the painting invites imagination to complete what is merely suggested. We see not only the Graces as mythological beings but also Rubens at work, shaping them from loose strokes into recognizable forms.

The swirling movement of the bodies, the warm glow of flesh against the earthy ground, and the subtle indications of a classical landscape all combine to create an atmosphere of joyous freedom. There is no sense of constraint or stiffness; everything flows. The figures appear unconcerned with being observed, absorbed in their own dance and conversation. This sense of unselfconscious ease is part of their charm and may reflect an ideal of sociable, unforced beauty that Rubens admired.

Legacy And Place Within Rubens’s Oeuvre

Rubens returned to the theme of the Three Graces multiple times, culminating in a large, highly finished canvas late in his career. This sketch can be seen as a step in that ongoing exploration. It encapsulates key aspects of his art: fascination with the human body, engagement with classical themes, love of dynamic composition, and enjoyment of rich painterly surfaces.

As part of his wider body of mythological works, the painting contributes to the Baroque revival of ancient stories as vehicles for exploring contemporary ideas about pleasure, virtue, and the role of art. The Graces, in Rubens’s hands, symbolize more than decorative beauty. They embody an ideal of generous, life-affirming joy—an ideal expressed not just in their subject matter but in the very way the paint is laid on the surface: abundant, energetic, and full of movement.