Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

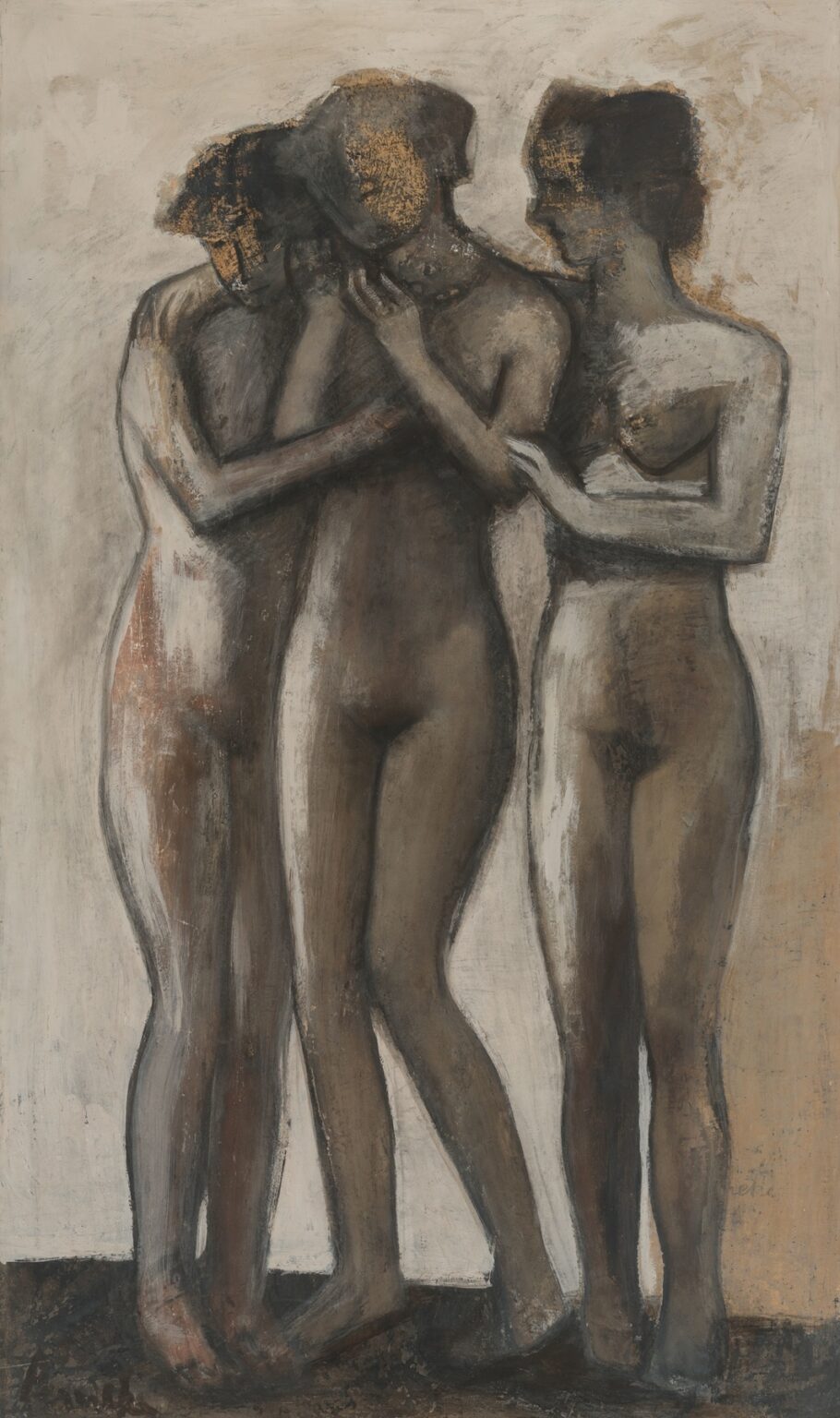

Constant Permeke’s The Three Graces (1949) stands as a monumental finale to the artist’s career and a poignant reflection on human solidarity in the aftermath of global upheaval. While the classical motif of the Three Graces—goddesses of beauty, fertility, and joy—has graced the canvases and marbles of European masters for centuries, Permeke reinterprets the theme through the lens of 20th-century Expressionism. Stripped of mythological trappings and drapery, his figures are raw, weighty embodiments of shared endurance. Painted just three years before his death, this work distills Permeke’s lifelong fascination with the human condition, rural labor, and elemental forces into a deeply felt allegory of communal resilience.

Historical Context and Artist’s Late Period

Permeke’s life spanned tumultuous eras: born in 1886, he witnessed World War I’s horrors, the interwar social upheavals, and the devastation of World War II. By 1949, Belgium was rebuilding both its cities and its sense of identity. Traditional rural communities, which Permeke had celebrated since the 1910s, were threatened by modernization and the trauma of occupation. In this climate, the artist retreated into his studio to contemplate themes of solidarity, renewal, and the very essence of humanity. The Three Graces emerged not as an escapist idyll but as a somber, grounded affirmation that unity and shared humanity could outlast conflict. The painting thus embodies both personal reflection and a broader social commentary on postwar reconstruction.

Classical Motif Reimagined

The Three Graces have historically symbolized charm, creativity, and fertility—often depicted as elegantly draped figures interlocking arms in a dance. Permeke dispenses with classical idealism and ornamental costuming. His Graces stand nude, their bodies rendered in earthy tones that speak of soil and season. Rather than delicate divinities, they are tangible women, flesh and blood merged in a sculptural mass. Their anonymity invites universal interpretation: they can represent any community bound by empathy and shared struggle. By anchoring an ancient theme in contemporary reality, Permeke bridges art-historical tradition with modern existential concerns.

Composition and Spatial Treatment

Permeke’s composition is deliberately austere. The three figures occupy the central vertical plane, their forms touching and overlapping to form a single cohesive block. The heads tilt toward the center, generating a circular flow that guides the eye. The background offers no horizon line or environmental cues—just a neutral wash in pale ochre and gray that recedes, emphasizing the figures’ monumentality. There is no illusion of deep space; the painting feels like a relief sculpture brought to life. This compression of depth intensifies the emotional gravity, foregrounding the human bond as the sole focus.

Color and Tonal Harmony

The amalgam of raw umber, burnt sienna, ochre, and muted gray forms a restrained palette that remains characteristic of Permeke’s later work. Flesh tones transition seamlessly from warm brown to cool gray, suggesting both bodily warmth and the shadows of suffering. Highlights—applied sparingly in chalk white—trace the gentle curves of shoulders, the subtle planes of faces, and the ridges of knuckles. The absence of bright or contrasting colors prevents any distraction, allowing the viewer to absorb the figures’ physical presence and emotional resonance. This earthbound color scheme roots the Graces in the realm of everyday life, far from mythic glamour.

Drawing and Underpainting

Technical analysis reveals a charcoal underdrawing beneath the oil layers, mapping the figures’ anatomy and ensuring structural coherence. A raw umber ground creates a warm mid-tone across the canvas, visible where paint is thin. This underpainting lends a subtle glow to the final work, as the earth tone shows through in areas of glazing. The combination of dark underlayers and lighter flesh passages creates a luminous depth, while occasional exposed canvas edges reinforce the immediacy of the painting process.

Brushwork and Surface Texture

Permeke’s brushwork is at once robust and nuanced. Broad, sculptural strokes model the limbs and torsos, conveying a sense of mass and weight. In contrast, the faces and hands receive more delicate, layered handling, with thinner paint and subtle blending. The juxtaposition of thick impasto and dry-brush scumbles generates a rich tactile surface. Scattered areas of exposed canvas lend an unfinished quality, as though the figures remain in a state of becoming. This painterly dynamism—oscillating between solidity and suggestion—imbues the work with life and movement, even in its solemn stillness.

Light, Shadow, and Mood

Rather than invoking a single directional light source, The Three Graces employs ambient illumination that seems to emanate from within the figures themselves. Highlights gently emerge along collarbones, knees, and the ridge of the nose, while deep, warm shadows pool in the hollows of the armpits and the spaces between legs. This internal glow reinforces the painting’s symbolic tenor: the light of shared humanity shining through collective darkness. The resulting mood is contemplative and dignified—free from theatrical drama yet imbued with quiet intensity.

Symbolic Resonances

Beyond the classical reference, Permeke’s Graces symbolize broader themes of reciprocity, mutual care, and spiritual sustenance. Their joined arms and interlocking shoulders convey an unspoken pact: to bear life’s burdens together. Viewed in the context of postwar despair, they become emblematic of communal healing. The nudity, far from erotic, suggests vulnerability—a willingness to stand bare before one another. By reconceiving grace as an act of solidarity rather than ornament, Permeke elevates everyday compassion to an almost sacred plane.

Relationship to Rural Subjects

Permeke is best known for his depictions of Flemish fishermen and farmers. In those works, bodies are oriented outward, against seas or fields, confronting the elements. The Three Graces turns inward: the figures face each other, not a landscape. Yet the same sturdiness of form and earthbound palette link this painting to his rural corpus. The heavy, grounded figures recall the physicality of peasants, while the profound stillness evokes the contemplative moments between labor. In this sense, Permeke extends his lifelong dialogue with elemental existence into an exploration of interpersonal connection.

Comparison with Contemporary Expressionism

While German Expressionists like Ernst Ludwig Kirchner and Käthe Kollwitz often rendered figures in emotional extremes, Permeke’s approach is more meditative. His forms are less distorted, more volumetric, and less overtly dramatic. In contrast to Abstract Expressionists emerging in the late 1940s, who celebrated spontaneity and gesture, Permeke retains a classical compositional rigor. Yet his pared-down palette and emphasis on psychological depth anticipate postwar European figurative movements. The Three Graces thus occupies a unique position: both a culmination of early 20th-century Expressionism and a precursor to later existential figuration.

Critical Reception and Influence

Upon its unveiling in Brussels in 1950, The Three Graces was hailed as a masterful synthesis of Permeke’s technical prowess and humanistic vision. Critics praised its “timeless empathy” and “subdued grandeur.” In subsequent decades, the painting influenced Belgian and Dutch artists exploring themes of communal resilience. Art historians now view it as Permeke’s late-career masterpiece—a work that encapsulates his journey from rural naturalism to distilled Expressionism.

Conservation and Exhibition History

The canvas underwent relining in the 1970s to address stress cracks and stabilize the paint surface. Restorers removed discolored varnish layers, reviving the original tonal subtleties. Today, The Three Graces resides in the Royal Museum of Fine Arts Antwerp, where it remains a highlight of the permanent collection. It has toured internationally, featuring in retrospectives on European Expressionism and exhibitions exploring gender, myth, and community in modern art.

Interpretive Possibilities for Modern Viewers

Contemporary audiences encounter The Three Graces in an age of social fragmentation and renewed pleas for empathy. The painting invites viewers to reflect on the bonds that unite disparate individuals. Interpretations range from feminist readings—emphasizing female solidarity—to psychological analyses of collective identity. The figures’ ambiguity allows personal projection: they might represent friends, family members, or abstract facets of self. In all cases, the work’s power lies in its ability to resonate across cultures and generations.

Conclusion

Constant Permeke’s The Three Graces (1949) stands as a profound testament to the human capacity for connection in the face of adversity. By reimagining a classical theme through his mature Expressionist style—characterized by earthy hues, vigorous brushwork, and monumental figuration—Permeke offers an image of shared grace that transcends myth and enters the realm of lived experience. In its austere beauty and emotional depth, the painting continues to speak to our collective need for solidarity, reminding us that in an often turbulent world, the greatest strength lies in standing together.