Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

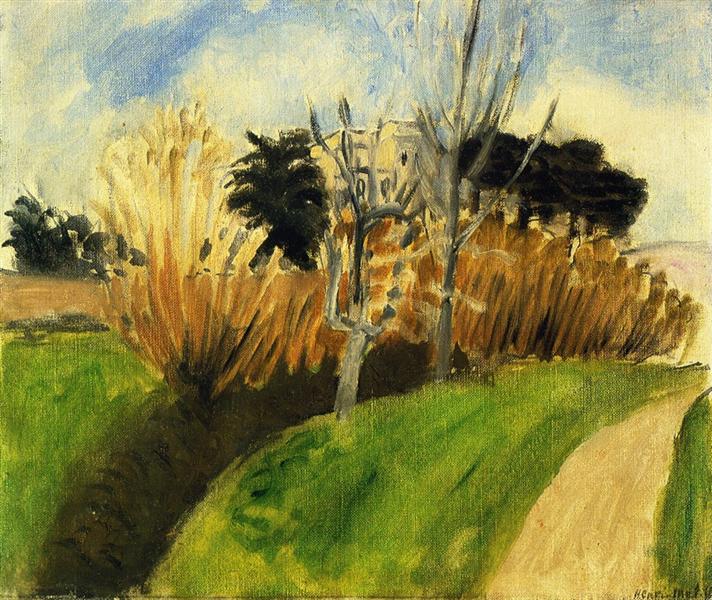

Henri Matisse’s “The Stream near Nice” (1919) captures a slice of Mediterranean countryside at the precise moment when winter yields to spring. Painted during the first phase of his Nice period, this landscape replaces the theatrical interiors and odalisque reveries people often associate with Matisse with a brisk, outdoor clarity. A dark watercourse cuts diagonally through vibrant grass. Tawny reeds flare up like torchlight before a stand of darker evergreens. Two leafless trees punctuate the middle ground with pale, angular trunks. A sandy path bends along the right margin and disappears. Overhead, a high, restless sky moves in swathes of blue and milky cloud. The scene is modest in subject yet grand in pictorial ambition: a field exercise in how color temperature, directional brushwork, and simplified forms can turn a small corner of terrain into an orchestration of light and movement.

Nice in 1919: A New Climate for Painting

After the trials of the war years, Matisse relocated to the Riviera and began working in an atmosphere he would later describe as one of “luminous clarity.” The Nice period is often summarized by interiors, shutters, and patterned textiles, but the first seasons also produced plein-air landscapes like this one. What he learned in rooms—how to use large planes, how to let pattern perform the duties of architecture, how to keep space shallow yet habitable—he brought outside. In “The Stream near Nice,” the components of the countryside become structural units. The stream is not simply water; it is a dark plane that organizes the foreground. Grasses and reeds are not botanical inventory; they are directional strokes that push the eye up and across the canvas. The path is both motif and geometric counterweight. The result is a landscape governed by designed relations while remaining faithful to observation.

First Look: A Diagonal World

The painting declares itself through a pair of diagonals that split the lower half like open arms. At left, the stream plunges from the corner toward the center, a slanted trench rendered as a deep, cool wedge. At right, the pathway ascends in a pale ochre ramp that lifts toward the distance. Between these vectors rises a wedge of saturated spring green, its upper edge battling the darker band of reeds. The middle ground thickens into ochre and gold, then suddenly breaks under a sheaf of blackish pines and a few bare, blue-gray trunks. The top third opens to sky. This architecture of diagonals creates propulsion without disorder; it is a walking picture, one that moves you forward as you look.

Composition: Anchors, Hinges, and Balances

Matisse builds the composition around three anchors and a hinge. The first anchor is the dark stream, which compresses the foreground and establishes a tonal base. The second anchor is the bright, grassy incline that occupies the center-right, a plane of high key color that counters the stream’s depth. The third anchor is the block of bronze reeds in the middle distance, a dense vertical mass that catches the light and arrests the advance. The hinge is the pair of leafless trees, set just to the right of center. Their trunks fork and splay, turning the composition upward and bridging the tonal jump from dark foreground to lit middle ground. Everything else—the black pines, the pale sky, the distant building glimpsed through branches—serves to balance these terms without diluting their force.

Color Architecture and Temperature

The palette is concise and structural. Cold greens and blue-grays govern the ground planes; ochres and warm oranges ignite the reeds; deep greens verging on black sketch the evergreens; the sky oscillates between cerulean and milk-white. Rather than blending these notes into neutrality, Matisse lets each color family keep its character, then positions them so their meeting lines vibrate. Where the spring grass touches the reed-bank, a warm-cool edge makes the green feel luminous. Where the stream meets the bank, a cool-on-cool boundary becomes depth. The bare trunks carry pale blues into the warm middle ground, knitting temperatures without smearing them. Because each color recurs across the canvas—the ochre of the reeds reappears in the path, the dark pine returns in the stream’s deepest shadow—the harmony reads as inevitable.

Light and Season

This is not summer abundance. It is the threshold of growth. The reeds retain their winter straw; the grass has greened; the trees at center are still leafless; the pines on the left cluster like held breath. The light is high and mobile, a late-morning sun passing through scattered cloud. Matisse translates this atmosphere by rejecting theatrical shadows in favor of temperature shifts. The sun warms the reeds into amber, but the wind-cooled stream remains a dark blue-green; the sky’s white is not chalk but air, scumbled thin enough that the canvas tooth participates in the light. The season is declared not by iconography but by the way paint behaves: fresh strokes, chilled shadows, a feeling of air moving through branches.

The Stream: A Dark Engine

The titular stream is painted less as sparkling water than as an organizing absence. Its color is the coolest, deepest in the picture, a mixture that pulls toward blue-black with submerged greens. Instead of depicting reflections or ripples, Matisse drags long strokes down the channel so that the form becomes a directional vector. As it narrows toward the middle ground, the stream pulls the eye into the meeting of reeds and tree trunks. This is the classic Nice trick: use a large, simple plane to perform the spatial work normally assigned to perspective lines. The stream becomes a pictorial engine, not just a motif.

The Path: A Warm Counter-Rhythm

On the right, the path answers the stream with a lighter diagonal. Its sandy tone warms the chromatic climate and opens a route into the middle distance. Where the stream’s edge is crisp, the path’s boundary softens into surrounding grass, a technical decision that makes the human way feel less cut and more trodden. The path’s curve also offsets the straight run of the stream; together they compose a subtle S that stabilizes the lower half of the canvas. The invitation is gentle but unmistakable: the landscape is walkable, the painting navigable.

Trees, Reeds, and the Gesture of Growth

Matisse draws trees as living gestures rather than botanical diagrams. The leafless trunks at center are blue-gray stems that fork into abrupt angles—two calligraphic assertions rising out of the reeds. By painting them cooler than their surround, he makes them luminous, as if winter’s pale sap were still coursing. The reeds are delivered in short, flared strokes that broaden as they rise, each a flame shape. Their cumulative effect is a vertical shimmer that sets the middle ground audibly vibrating. Behind them, the dark pines mass into silhouettes with hooked edges and deep hollows, the way distance folds detail into tone. These three manners—angular trunk, flared reed, pooled pine—establish a vocabulary of growth that is legible at a glance.

Brushwork and Surface

The surface reveals a painter working fast enough to keep energy in the mark, slow enough to place each plane deliberately. The grass is built from swathes of semi-opaque green laid in with a broad brush; the reeds are shorter, loaded touches that leave ridges; the trunks are single, confident pulls; the sky is a blend of soft scumbles pushed thin so that the weave of the canvas imparts atmospheric grain. There is no laboring after finish. Matisse allows under-color to show through at edges, creating the sparkle of daylight without literal highlights. This economy of means is central to the picture’s freshness.

Space: Shallow, Convincing, Designed

Depth is achieved through overlaps and tonal sequencings rather than through meticulous linear perspective. The stream overlaps the grass; the reeds overlap the stream; the trunks overlap the reeds; the pines and the pale, distant building overlap the sky. Values step from dark foreground to medium middle ground to higher key distance. Yet nothing recedes into a deep vanishing tract; the picture remains a designed surface. This duality—flatness that admits world—was the Nice period’s hard-won balance, and it is on full display here.

The Distant Architecture

Between the trunks, barely articulated, sits a pale structure—perhaps a farmhouse or villa—more silhouette than building. It is the painting’s quietest note and its most human. Matisse withholds detail so the architecture reads as a memory nestled inside growth rather than as a destination. The human world is present in the path and this building, but the picture gives primacy to land and light. This balance—acknowledging habitation without turning the landscape into anecdote—allows the painting to remain elemental.

Rhythm and the Eye’s Path

“The Stream near Nice” teaches a specific way to look. Begin at the lower left, where the stream opens like a door. Travel up the dark channel to the flare of reeds; rest on the pale forked trunks; slip right along the ridge of grass; follow the sand path up and around; pause at the soft, black pines; lift to the sky. Repeat the circuit and the painting clarifies itself as a sequence of breaths—inhale along the stream, exhale across the path, inhale through the reeds, exhale into the sky. The rhythm is not rhetorical; it is physiological, and it is what makes the small canvas feel large.

Emotion Without Story

Matisse avoids narrative cues. There are no figures, no animals, no explicit weather events. Yet the painting contains emotion: a quiet exhilaration particular to the first greenings of the year. The diagonal thrusts are active but not agitated. The sky is open but not heroic. The reeds glow but do not blaze. This measured lift is consistent with Matisse’s postwar ethic: refuse spectacle and build a durable happiness from proportion, color, and air.

Kinships Within 1919

Viewed alongside “The Promenade” and “Landscape, Nice,” this canvas forms a trio of outdoor meditations. In each, Matisse uses a dark diagonal—stream, path, or shadow—to key the foreground, then opposes it with illuminated grasses and simplified tree masses. The interiors from the same year—windows, mirrors, red-lattice floors—employ a similar logic: a large plane that structures the scene, a network of repeating rhythms, and a palette organized into warm and cool families. “The Stream near Nice” reveals that the Nice vocabulary was never confined to rooms; it was discovered in the climate of the Riviera and then practiced both indoors and out.

Likely Palette and Materials

The painting’s clarity suggests a concise set of pigments handled opaquely with sparing translucence. The greens likely combine viridian or chromium oxide with yellow ochre and white, warmed in the sunlit slopes and cooled in the stream. The reeds pull from yellow ochre and raw sienna touched by cadmium yellow; the path shares this family minus the darker sienna. The trunks carry lead white cooled with ultramarine and a whisper of black; the pines deepen with ultramarine mixed into ivory black for a blue-black density. The sky is cerulean married to lead white, scumbled thin in places to let ground tone vibrate. Such a palette, small and strongly keyed, lets Matisse tune temperature rather than chase descriptive detail.

How to Look, Practically

Stand close and count the decisions. Notice how the stream is a single family of dark strokes, not a rendered picture of water; how the grass is a few swathes turned by temperature; how the reed-bank is built from short upstrokes that flare at the top; how the trunks are drawn with one gesture each. Step back and feel the diagonals cohere into a spacious order. Move side to side and watch the colors flicker at edges where warm meets cool. Then return to the small pale building and sense how the entire landscape shelters it without competing for attention. The more you travel this route, the more the picture repays with steadiness.

Why This Landscape Matters

“The Stream near Nice” is a compact statement of Matisse’s belief that color-built structure can carry the weight of both sensation and memory. The painting proves that a landscape need not depend on atmospheric tricks or descriptive labor to feel true. By simplifying forms and clarifying temperatures, Matisse captures not a botanical inventory but a lived interval—the quickening of early spring, the walk along a path, the sound of water running under reeds, the crispness of trunks in moving air. It is a realism of relations, achieved with the fewest possible means.

Conclusion

In 1919 Henri Matisse found in the Riviera a climate for a new kind of clarity. “The Stream near Nice” distills that clarity into a landscape whose diagonals carry you, whose colors breathe, and whose brushwork makes weather out of paint. The stream anchors, the path invites, the reeds glow, the trunks lift, the sky opens. Nothing is staged, everything is placed. The canvas is not large, but it contains a walk, a season, and a proposition: that happiness in painting is built from the right proportions of cool and warm, dark and light, near and far. It is a promise kept in every square inch.