Image source: artvee.com

Franz von Stuck’s “The Spring”: A Portal to Sensual Symbolism

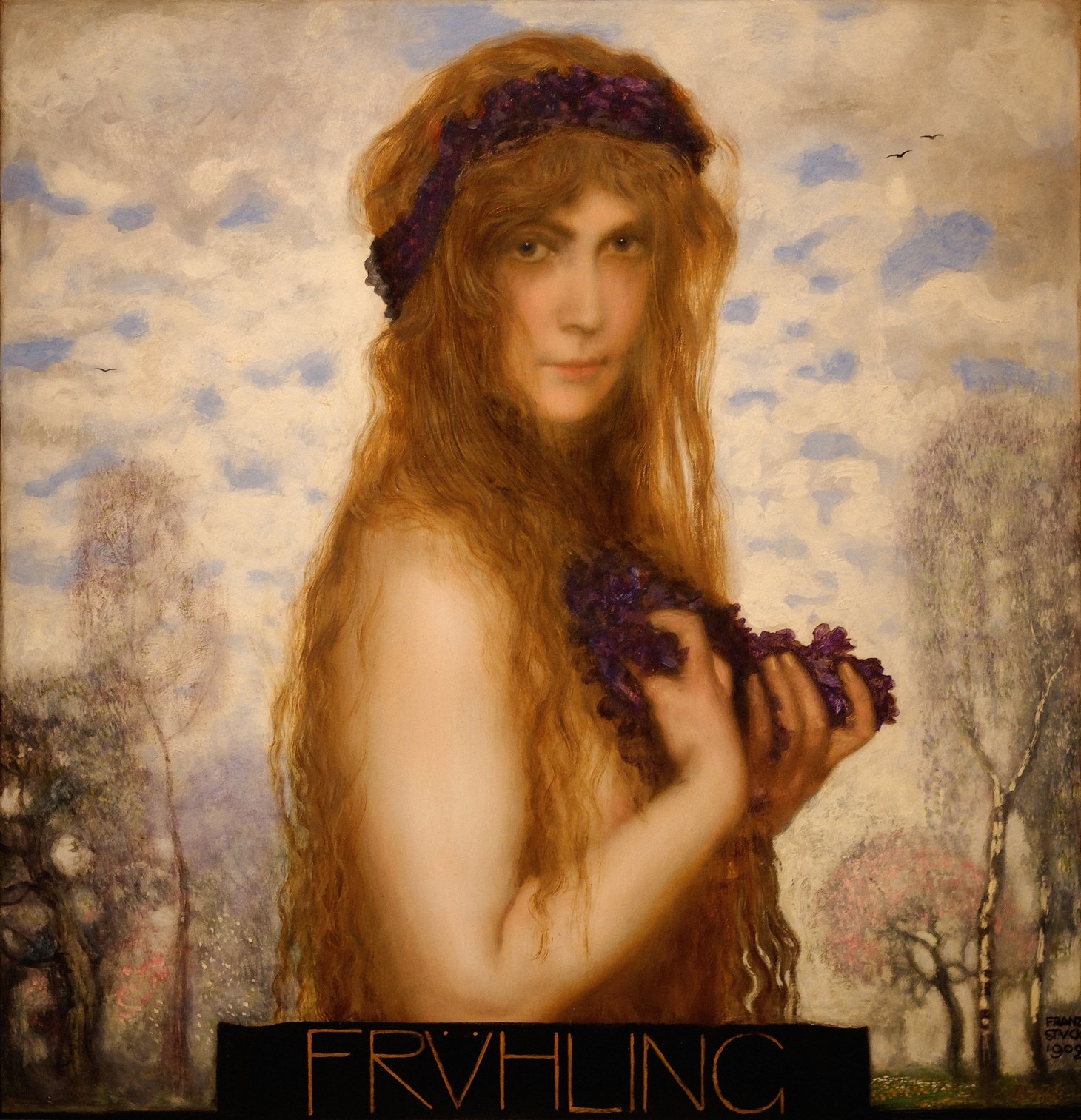

Franz von Stuck’s The Spring (Frühling, 1902) is a quintessential example of fin-de-siècle Symbolist art, blending mysticism, sensuality, and nature into a composition that appears deceptively serene yet richly charged with allegorical meaning. The painting stands as a meditation on rebirth, femininity, and the eternal cycles of nature, conveyed through the arresting figure of a woman bathed in soft light and framed against a delicately rendered landscape.

Stuck, known for his mythological themes and mastery of both eroticism and spirituality, moves away here from his darker allegories and ventures into a more luminous, yet still enigmatic, realm. The Spring is not merely a seasonal personification—it is a vision of life at its tender, intoxicating awakening, filtered through the lens of an artist deeply aware of both classical tradition and modern psychological undercurrents.

The Central Figure: Embodiment of Nature and Renewal

The nude woman who dominates the canvas is not a passive subject. She is the personification of spring, not only in title but in aura. Her long, flowing, reddish-gold hair frames a face that is at once youthful and ancient. She gazes directly at the viewer with an expression that mixes innocence and knowledge, seduction and stillness. Her bare shoulders and chest are rendered with an almost porcelain-like softness, while her hands cradle a cluster of violet flowers, reinforcing the symbolism of growth, bloom, and sensual vitality.

This central figure embodies the essence of springtime: vulnerable, fertile, and alluring. Yet there is a self-possession in her gaze. She does not present herself to be seen; she sees. This small reversal in agency transforms the painting from a traditional male gaze portrait into something more psychologically complex. She is not an object of nature—she is nature itself, aware, breathing, and in control of her own blossoming.

The Use of Lilac and Floral Symbolism

The purple flowers in her hands and woven into her hair are most likely lilacs, a bloom traditionally associated with spring, renewal, and first love. Lilacs, in Western symbolism, also evoke memory and youth. By incorporating them into her adornment and grasp, Stuck creates a layered metaphor: the woman is not just blooming; she is the keeper of bloom, the guardian of ephemeral beauty.

Their color, deep violet, has spiritual and mystical connotations. It is the color of twilight, of transition between day and night. Similarly, spring is a moment of passage between winter’s death and summer’s fullness. In this transitional space, the figure exists as a goddess of liminality—poised between innocence and desire, silence and song.

Background and the Language of Landscape

The landscape behind her, though softened and impressionistic, plays a critical role. The sky is filled with puffy, cool clouds scattered across a serene blue. Sparse trees line the horizon, their branches tinged with the first hints of green and blush, evoking early spring. Two birds fly in the upper right, subtle symbols of awakening and migration, reinforcing the theme of return and transformation.

Unlike the figure, the landscape does not demand attention—it supports and surrounds. It acts as a mirror to the inner state of the woman, echoing her serenity, freshness, and latent promise. The trees appear almost spectral, not fully emerged from winter’s shadow. They are in the process of becoming, just as she is.

The background contributes not only to mood but also to the symbolic layering of the work. Nature is not merely decorative but integral to understanding the painting’s theme. Every detail—the softness of the clouds, the fragility of budding trees, the translucence of the light—converges to situate the viewer in the very heart of spring.

The Hair as an Emblem of Vital Energy

One of the most striking features of The Spring is the flowing cascade of hair that frames the woman’s face and cascades down her shoulders and back. In Symbolist art, hair frequently acts as a metaphor for natural forces—instinct, sensuality, and growth. Here, the hair seems almost animate, as though it too is sprouting and reaching toward warmth.

Rendered with exquisite detail and softness, the hair blurs the line between the human and the natural. It is not simply hair—it is vegetation, current, and aura. Its vivid color and abundance suggest vitality, youth, and eroticism. Yet its subtle movement and integration with the flowers in her crown imply an organic oneness with the earth. She is not adorned with spring—she is spring.

Light and Skin: The Radiance of New Life

Stuck’s treatment of light is another essential element in this painting. The figure’s skin is luminous, soft, and pale—qualities that suggest both purity and newness. There is a warm internal glow, a diffuse light that touches her body but does not come from a visible source. This lends her an almost divine quality, a subtle radiance that transcends realism.

This divine lighting contrasts with the cooler tones of the background, intensifying her presence. It creates a gentle halo effect that elevates her from mere model to allegorical figure. The light does not just illuminate her—it emanates from her, symbolizing the life-giving force of spring.

Typography and the Framing Device

At the bottom of the painting is the word “FRÜHLING” inscribed in gold against a black band. This framing device anchors the painting with a visual statement, bridging the image with graphic design. The typography is modern and stylized, hinting at Art Nouveau aesthetics. It transforms the painting into a visual poster or icon, not unlike the sacred altarpieces of religious art.

This modernist touch reminds the viewer that Stuck is not merely emulating classical motifs—he is updating them. The use of text in visual art, especially with this kind of elegant modern script, reflects a fin-de-siècle interest in synthesis between fine and applied arts. The label doesn’t just name the subject—it solidifies her archetype. She is The Spring, not a spring.

Eroticism Without Voyeurism

Franz von Stuck was no stranger to eroticism in his work, often walking the line between the sacred and the profane. In The Spring, nudity is present, but never exploitative. The figure’s posture is relaxed, her arms modestly gathered, her breasts not overtly displayed. There is an intimacy here, but also a refusal to be objectified. Her gaze counters voyeurism, returning scrutiny rather than submitting to it.

This refusal to titillate makes the painting even more powerful. The sensuality is there—in her skin, her hair, her flowers—but it is sublimated into symbol. She is not a courtesan or a nymph. She is a season, an archetype, a moment of the earth come to life. In this way, the erotic becomes spiritual, elemental, and timeless.

Mythic and Pagan Undercurrents

There are also mythological resonances at play in The Spring. The image evokes pagan goddesses like Flora, Persephone, or even Ostara—the Germanic goddess of dawn and fertility. Each of these figures is tied to the awakening of the natural world, to rebirth and the return of warmth. Though Stuck offers no explicit mythological symbols, the connections are clear in mood and iconography.

This mythic underpinning reinforces the figure’s timelessness. She is not a portrait of a particular woman but a visual incarnation of a concept—a sacred moment in the turning of the year. This universality allows her to transcend her context, making the painting as relevant today as it was in 1902.

Modernism and the Evolution of the Female Ideal

Stuck’s rendering of womanhood in The Spring also reflects broader changes in the representation of the female figure in early modernist art. Gone are the classical Venus forms or the sentimental Madonnas of earlier periods. Here, the woman is strong, independent, and rooted in the natural world rather than the divine or domestic.

She is powerful in her stillness, commanding in her calm. Her beauty is not ornamental but symbolic. This modern femininity aligns with the broader Symbolist tendency to portray women as conduits to deeper truths—emotional, spiritual, and cosmic. Stuck embraces this evolution, presenting a woman who is both subject and symbol, both figure and force.

The Intersection of Painting and Design

One of the unique elements of Franz von Stuck’s artistry is his fusion of painting with design principles. In The Spring, this synthesis is evident in the use of framing, typography, and composition. The image is symmetrical but organic, balanced but free-flowing. The strong rectangular structure is softened by the curves of hair, clouds, and flowers.

This marriage of design and fine art reflects the ethos of the Art Nouveau movement, which sought to dissolve boundaries between high and decorative arts. Stuck, as both painter and architect, often designed his own frames and interiors. Here, the painting’s structure suggests that it might have once lived not only in a gallery but in a domestic or sacred space—part of an integrated aesthetic experience.

Timeless Beauty in Seasonal Form

More than a depiction of springtime, The Spring is an ode to cyclical beauty—the eternal return of warmth, bloom, and possibility. It celebrates femininity not just as biology or allure but as a cosmic principle. The woman is not a character; she is a condition of the earth.

The painting invites the viewer into a moment of stillness and admiration. It does not demand interpretation through narrative. Instead, it speaks through symbols, light, and mood. Like spring itself, it resists control and offers renewal through presence. Franz von Stuck’s vision remains a testament to the power of art to elevate the ordinary—flowers, clouds, skin—into the sacred.

Conclusion: “The Spring” as Sacred Sensuality

In The Spring, Franz von Stuck masterfully fuses the erotic, the symbolic, and the natural to create a vision that is both timeless and thoroughly modern. The painting stands as an icon of fin-de-siècle Symbolism—lush, luminous, and layered with meaning.

It is a reminder of the power of art to transcend literalism and evoke the invisible rhythms that shape human life: desire, change, and renewal. The woman of The Spring does not speak, yet she communicates everything. Through her gaze, her flowers, and her quiet command, she embodies the eternal return of life after darkness.