Image source: artvee.com

Introduction to The Sin

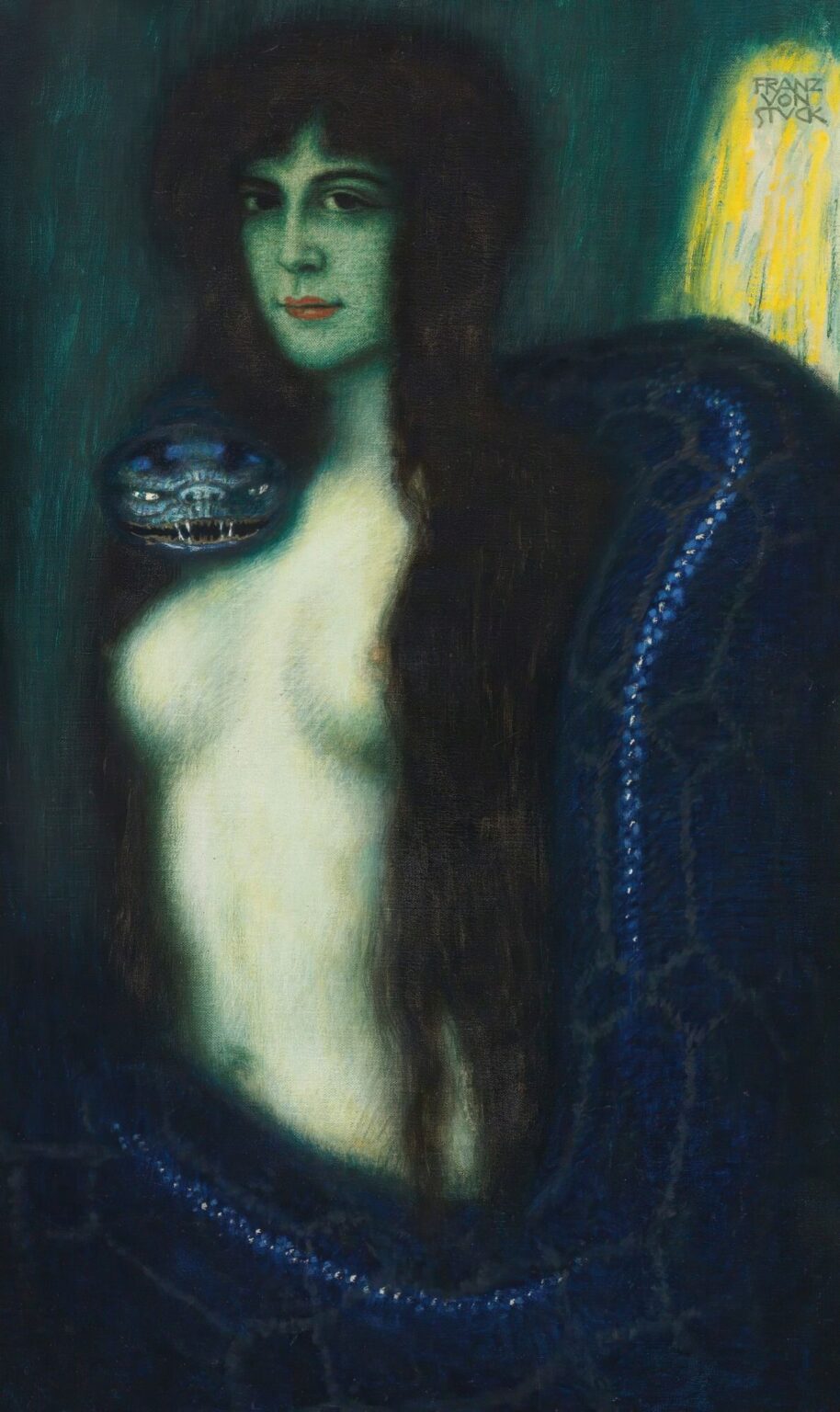

Franz von Stuck’s The Sin (1893) stands as a landmark of Symbolist painting, fusing mythic drama, psychological intensity, and pioneering use of the female nude as an allegorical figure. In this iconic canvas, von Stuck confronts viewers with a half‑hidden woman entwined by a serpent, her face turned in a gaze that mingles defiance and vulnerability. Set against an ambiguous, fiery background, this figure embodies both temptation and transgression, drawing upon Christian iconography of Eden and original sin while transcending literal representation to probe universal themes of guilt, desire, and self‑knowledge.

Historical and Artistic Context

By the early 1890s, Franz von Stuck had emerged as a leading figure in Munich’s vibrant art scene. A co‑founder of the Munich Secession in 1892, he and his contemporaries rejected academic conservatism, seeking new means of expression that could convey inner experience rather than surface appearance. Influenced by Symbolist currents in France and Belgium, von Stuck began to explore mythological and allegorical subjects, melding classical form with modern psychological depth. The Sin was unveiled at the 6th International Art Exhibition in Munich in 1893, where its bold eroticism and dramatic symbolism sparked controversy and fascination. The painting inaugurated von Stuck’s reputation as a master of dark, visionary imagery, leading to his appointment as professor at the Munich Academy and cementing his influence on a generation of German artists.

Subject Matter and Iconography

At its core, The Sin invokes the story of Eve and the serpent, yet von Stuck abstracts the narrative to create a more universal emblem of human transgression. The central figure—a stylized, idealized woman—appears half‑draped, her rippling golden hair cascading around pale shoulders. A sinuous, cobalt‑blue serpent coils around her neck and torso, its gleaming fangs and reptilian gaze underscoring the lethal seduction of forbidden knowledge. The woman’s own eyes, half‑closed and framed by long lashes, hold a dual expression: she seems simultaneously enraptured by the serpent and complicit in its deadly embrace. Behind her, a pool of crimson light blazes against shadowy darkness, evoking both the fire of original sin and the burning consequences of moral choice.

Composition and Spatial Dynamics

Von Stuck organizes the composition with ritualistic precision. The canvas is bisected vertically by the woman’s form, which curves in an undulating S‑shape from head to hip. This serpentine line echoes the coiling snake, visually binding the two figures. The negative space around them—an enveloping void of deep greenish black—enhances the sense of isolation and otherworldliness. Light radiates from behind the figures, forming a luminous halo that amplifies their drama. The horizontal plane of the frame’s lower edge and the suggestion of an altar or pedestal stabilize the composition, anchoring the mythic scene in a quasi‑religious context. This interplay of curves, light, and void creates a charged tension, drawing viewers into the painting’s symbolic web.

Use of Color and Symbolic Resonance

Color in The Sin serves both aesthetic and emblematic functions. The woman’s skin is rendered in creamy, almost phosphorescent whites, contrasting starkly with the serpent’s jewel‑like blues. Von Stuck places splashes of ruby red behind the figures, suggesting fire, blood, and the burning pangs of conscience. Greenish shadows around the edges evoke the underworld or moral ambiguity. The serpent’s scales, depicted in shifting tones of indigo and emerald, catch the light with an otherworldly shimmer, emphasizing its supernatural potency. This controlled palette achieves emotional impact: the cold brilliance of the flesh suggests purity violated, the fiery backdrop conveys damnation’s imminence, and the snake’s cool hues underscore temptation’s beguiling allure. Together, these colors weave a visual allegory of sin’s multifaceted nature—both seductive and destructive.

Light, Shadow, and Chiaroscuro

Chiaroscuro—the dramatic interplay of light and shadow—lies at the heart of von Stuck’s technique in The Sin. A strong backlight creates a luminous halo around the woman and serpent, intensifying their silhouettes against the dark background. Highlights glimmer on the serpent’s scales, the woman’s cheekbones, and the sheen of her hair, lending them sculptural relief. Shadows obscure parts of her form—one breast and portions of her torso dissolve into darkness—suggesting moral ambiguity and psychological depth. This tension between illumination and concealment not only heightens the painting’s theatricality but also symbolizes the inner conflict of the sinner: moments of self‑recognition alternating with denial and self‑deception. Von Stuck’s mastery of tonal transitions thus becomes a means of exploring guilt’s shifting contours.

The Female Figure as Symbol

In The Sin, the female figure transcends portraiture to become an archetype of humanity’s vulnerability to temptation. Von Stuck draws on classical precedents—Venus, Psyche, and other mythic women—while embedding Christian connotations of Eve, the mother of all living who first partook of the forbidden fruit. Yet the woman here is not depicted as a passive victim but as an active participant in her own downfall: the serpent coils knowingly, and her gaze, though entranced, is not entirely submissive. Her lips, tinted with a hint of red, recall both seduction and the drawing of blood. The painting thus subverts conventional morality tales by granting the sinner dignity and agency, inviting viewers to empathize with her plight rather than condemn her outright. In von Stuck’s vision, the female figure embodies both the promise and perils of freedom.

Mythic and Psychological Dimensions

The Sin operates on two interlocking levels: mythic and psychological. On the mythic plane, it reinterprets the Edenic fall as an eternal drama, a perpetual cycle of innocence lost and knowledge gained. The serpent and woman stand in eternal confrontation, locked in a cosmic dance of seduction and resistance. Psychologically, the painting probes the inner recesses of desire and guilt: the woman’s half‑closed eyes and slightly parted lips convey the intoxicating thrill of transgression, while the surrounding darkness and fiery glow foretell the consuming consequences of that act. Von Stuck’s painting thus becomes an allegory of the human condition: our insatiable yearning for experiences beyond moral boundaries, and our haunting awareness of the price we pay for those illicit pleasures.

Technical Execution and Brushwork

A closer look at The Sin reveals von Stuck’s nuanced handling of oil paint. The background’s rich reds and blacks emerge from layered glazes, each thin wash building depth and luminosity. The woman’s flesh is achieved through a combination of soft blending and precise brushstrokes that model her form with anatomical accuracy and poetic idealization. The serpent’s scales are rendered with small, rhythmic strokes, producing a tactile interplay of light and shadow that enhances its predatory realism. Von Stuck varies his brushwork according to material: fluid for flesh, stippled for scales, and broad for the fiery backdrop. The final varnish unifies these disparate textures, giving the painting a jewel‑like sheen that underscores its visionary character.

Reception and Influence

Upon its exhibition in 1893, The Sin elicited strong reactions—admiration for its technical brilliance and symbolic depth alongside criticism for its erotic subject matter and dark vision. Nonetheless, the painting secured von Stuck’s international reputation as a leading Symbolist, influencing artists in Germany and beyond. His students at the Munich Academy, including Max Beckmann and Paul Klee, absorbed his emphasis on psychological intensity and mythic themes, helping usher in Expressionism. The Sin also contributed to broader conversations about the female nude in modern art, challenging viewers to confront the moral and aesthetic complexities of erotic power. Today, the painting remains one of von Stuck’s most studied works, featured prominently in exhibitions on fin‑de‑siècle art and the evolution of psychological symbolism.

The Frame as Extension of Meaning

Von Stuck often designed custom frames that complemented his paintings’ thematic concerns, and The Sin is no exception. The gilded, angular frame—visible in reproductions—echoes the painting’s interplay of light and dark. Its prismatic edges catch ambient illumination, reinforcing the painting’s jewel‑like glow. The frame’s austerity and elegance mirror the canvas’s formal balance between ornament and restraint. By integrating frame and painting, von Stuck created a unified art object, where the viewer’s transition from world to image is carefully calibrated to heighten the work’s symbolic potency.

The Sin and Contemporary Relevance

More than a century after its creation, The Sin retains its power to provoke reflection on desire, guilt, and the human psyche. In an era of unprecedented freedoms—and attendant moral ambiguities—the painting’s exploration of boundary‑crossing resonates with contemporary audiences. The serpent’s seductive power finds parallels in modern temptations: technological enticements, addictive behaviors, and ethical compromises. The woman’s conflicted gaze mirrors our own ambivalence toward those enticements. In exhibitions and art historical discourse, The Sin continues to serve as a touchstone for debates about representation, morality, and the psychology of transgression.

Conclusion

Franz von Stuck’s The Sin stands as a masterful fusion of technical prowess, symbolic complexity, and psychological depth. Through its dramatic composition, controlled palette, and visionary brushwork, the painting transforms a familiar biblical motif into a universal allegory of human desire and downfall. The entwined figures of woman and serpent, set ablaze by fiery backlight and cast into abyssal shadow, embody the eternal tension between freedom and consequence. As both a historical landmark of Symbolist art and an enduring mirror to the human soul, The Sin continues to captivate, challenge, and inspire viewers across generations.