Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

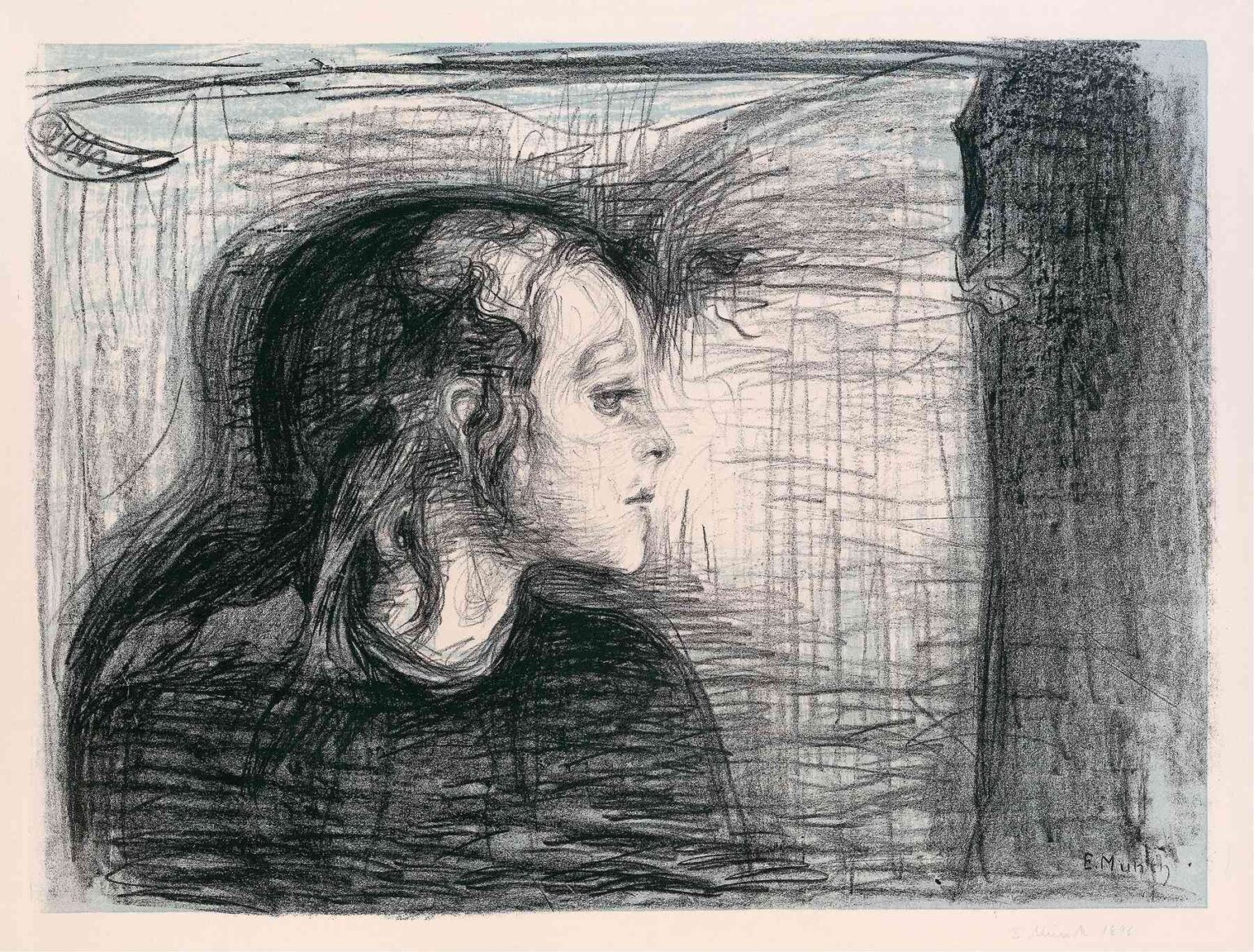

Edvard Munch’s The Sick Child I (1896) marks a pivotal moment in the artist’s exploration of grief, memory, and the fragility of life. Rendered as a pastel and pencil on paper, this early version of the celebrated motif depicts a young girl lying ill on a bed, her mother leaning over in a blend of care and despair. With its expressive lines, muted color washes, and haunting atmosphere, the work transcends anecdotal representation to become a universal meditation on suffering and loss. In this analysis, we will examine how Munch’s formal choices—composition, color, technique—combine with deeply personal and symbolic content to create a painting of profound emotional resonance.

Historical and Biographical Context

By 1896, Edvard Munch (1863–1944) had already suffered the early deaths of his mother and sister Sophie to tuberculosis. These traumas profoundly shaped his artistic vision, steering him toward themes of mortality and psychological introspection. Beginning in 1889, Munch began sketching images of his young sister as she lay dying, and over the following years he revisited the subject in various media—drawing, lithography, woodcut, and painting—ultimately producing four major versions of The Sick Child. The 1896 version, created in Kristiania (now Oslo), coincided with Munch’s deepening involvement in Symbolist circles and his embrace of art as a means to externalize inner emotional states. His diary entries from this period emphasize his belief that art must convey “the beholder’s inner life,” and in The Sick Child I, we witness one of the earliest, most direct realizations of that conviction.

Composition and Spatial Arrangement

Munch constructs The Sick Child I around a horizontal axis defined by the bed on which the ill girl reclines. The child occupies the left foreground, her pale face and upper body bathed in a diffused light that contrasts with the darker surroundings. Opposite her, the mother’s figure leans inward, her form articulated through a network of agitated, overlapping strokes. The spatial recession is shallow: walls and furniture recede minimally, collapsing the room into an ambiguous, almost claustrophobic space. This compression mirrors the emotional intensity of the scene, as if the boundaries between figures and environment have dissolved under the weight of grief. A window high on the back wall introduces a ray of daylight, but its small scale and distant position underscore the characters’ confinement. The composition thus guides the viewer’s focus to the interaction between mother and daughter, eliminating extraneous distractions and heightening intimacy.

Color Palette and Light Effects

Unlike the vivid oranges and blues of Munch’s later paintings, The Sick Child I relies on a subdued palette of grays, greens, and browns, with pale pinks and whites accentuating flesh tones. Munch applied pastel in loose, layered washes, allowing the paper’s natural ivory ground to glow through and lend the scene a spectral luminosity. The child’s face appears almost translucent, her cheeks rendered with barely-there pink strokes that underscore her frailty. In contrast, the mother’s dark garments absorb the surrounding hues, her form defined by dense, overlapping pencil lines. The muted greens of the bedspread and wallpaper suggest both the antiseptic atmosphere of a sickroom and the pallor of illness. Light enters sparsely through the high window, creating soft highlights on the child’s hair and sheet folds. By restraining his palette, Munch focuses on tonal relationships—light against dark, soft pastels against hard graphite—to evoke the pallor of sickness and the tension between hope and despair.

Technique and Artistic Process

Munch’s integration of pastel and pencil in The Sick Child I demonstrates his experimental approach to media. He began with broad pastel areas, lightly blocking in forms with swift strokes that emphasize texture over precision. He then sharpened details with graphite and charcoal, his lines often left visible as a record of his hand’s movement. The result is a dynamic surface where the roughness of the pencil contrasts with the softness of the pastel. Munch allowed smudges and accidental marks to remain, embracing the medium’s unpredictability as a metaphor for the fragility of the human body. Infrared reflectography reveals underdrawings where Munch adjusted the figures’ positions—particularly the mother’s looming posture—underscoring his concern for psychological impact over static depiction. This layered process emphasizes art as an act of remembrance and feeling rather than mere transcription.

Symbolism and Thematic Interpretation

While The Sick Child I depicts a specific personal tragedy, its imagery carries universal symbolic weight. The child’s pallor and the mother’s haggard countenance evoke the archetype of the dying youth and the mourning parent, themes present in religious art yet here stripped of devotional context. The high, small window suggests divine light or the prospect of transcendence but remains distant and limited—a faint promise rather than a fully realized salvation. The blurred boundaries between figures and room hint at the porous frontier between life and death, self and loss. Scholars have read the bedspread’s swirling patterns as visual metaphors for anxiety and feverish delirium, while the mother’s stooped posture conveys both protectiveness and the crushing weight of anticipated bereavement. In synthesizing these elements, Munch transforms a domestic scene into an emblem of existential crisis, where the border between presence and absence becomes the painting’s central focus.

Psychological Dimensions

Munch’s writings reveal his conviction that true art arises from “subjective sensation.” In The Sick Child I, the psychological interplay between mother and daughter is conveyed through gesture and atmosphere rather than narrative detail. The girl’s half-closed eyes suggest moments of pain and lucidity; her slight tilt toward the mother indicates trust tinged with weariness. The mother’s hand, reaching toward the child but never quite touching, embodies the conflicted emotions of longing, helplessness, and dread. The smudged, restless background lines mirror the turmoil of the mind, suggesting an internal landscape as turbulent as any external storm. In the absence of overt facial expression—particularly the child’s subdued features—the viewer projects their own anxieties onto the scene, intensifying the shared experience of vulnerability and empathy.

Relation to Munch’s Broader Oeuvre

The Sick Child I inaugurates a series of works in which Munch revisited illness and mortality, including oil paintings and prints such as The Sick Child II (1907) and The Voice of the Children (1899). Across these versions, Munch varied composition and media but returned consistently to the haunting tension between caregiver and patient. Unlike his more theatrical pieces—The Scream (1893) or Madonna (1894–95)—the Sick Child group unfolds in intimate interiors, emphasizing quiet emotional resonance over external drama. This focus on the private sphere complements Munch’s interest in psychological states, prefiguring later Expressionist explorations of interiority. The Sick Child motif also underscores Munch’s belief in cyclical artistic themes: he considered certain subjects inexhaustible wells of feeling, each iteration revealing new layers of meaning. In this sense, The Sick Child I serves as both a personal catharsis and an enduring framework for his most profound artistic inquiries.

Reception and Legacy

When first exhibited in Kristiania’s Høstutstillingen (Autumn Exhibition) of 1896, The Sick Child I attracted critical attention for its raw emotional content and innovative technique. Some contemporaries found its loose handling and somber mood unsettling, while progressive voices lauded Munch’s courage in confronting taboo subject matter. The work’s influence extended beyond Norway, resonating with artists in Berlin and Paris who were exploring Symbolist and early Expressionist aesthetics. In subsequent decades, art historians have framed the Sick Child series as foundational to modern art’s engagement with personal trauma and psychological depth. Both the 1896 version and later renditions have been featured prominently in major retrospectives—at the Munch Museum in Oslo and international venues—and remain central to scholarship on art and mourning. Contemporary artists continue to reference Munch’s synthesis of gesture, medium, and feeling when addressing themes of illness, loss, and familial bonds.

Conservation and Provenance

Original pastel and pencil works on paper, such as The Sick Child I, require meticulous care due to the fragility of pastel pigments and paper. Conservation efforts focus on maintaining stable humidity and low light levels to prevent pigment migration and paper yellowing. Scientific imaging—microfade testing and digital microscopy—has documented Munch’s layered application, guiding restorers in preserving the delicate balance between pastel and pencil. Provenance records trace the 1896 version through private Norwegian collections before its acquisition by the National Gallery (now the National Museum, Oslo) in the mid-20th century. The artwork’s condition reports note minor surface abrasion in the lower margin—likely from handling—underscoring the challenges inherent in exhibiting works on paper. Despite these vulnerabilities, The Sick Child I remains remarkably vibrant, its emotional power undimmed by time.

Broader Cultural Significance

Beyond the art world, The Sick Child I resonates as a visual archetype of parental grief and child mortality—a theme that transcends era and geography. Its imagery has informed literature and film dealing with family illness, inspiring scenes where caregivers hover in uncertain limbo between hope and despair. In psychoanalytic discourse, the work often appears as a case study in the visualization of mourning processes and transferential dynamics between patient and caretaker. In medical humanities, educators use Munch’s pastel to discuss the emotional dimensions of caregiving and the representation of illness in art. Even in contemporary visual culture, echoes of the Sick Child motif emerge in photographic series and installations addressing epidemics, chronic illness, and the emotional labor of caregiving, testifying to Munch’s enduring influence on how we picture and process human vulnerability.

Conclusion

The Sick Child I stands as a testament to Edvard Munch’s conviction that art should convey the depths of lived experience. Through its carefully constructed composition, muted yet expressive palette, and pioneering mixed-media technique, the work transforms a personal tragedy into a universal emblem of suffering and compassion. Its multilayered symbolism—thresholds between life and death, presence and absence—continues to captivate viewers, inviting reflection on the most fundamental aspects of human existence. Over a century after its creation, The Sick Child I endures as one of Munch’s most poignant achievements: a painting that lays bare the fragility of life and the enduring power of art to bear witness to our shared vulnerabilities.