Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

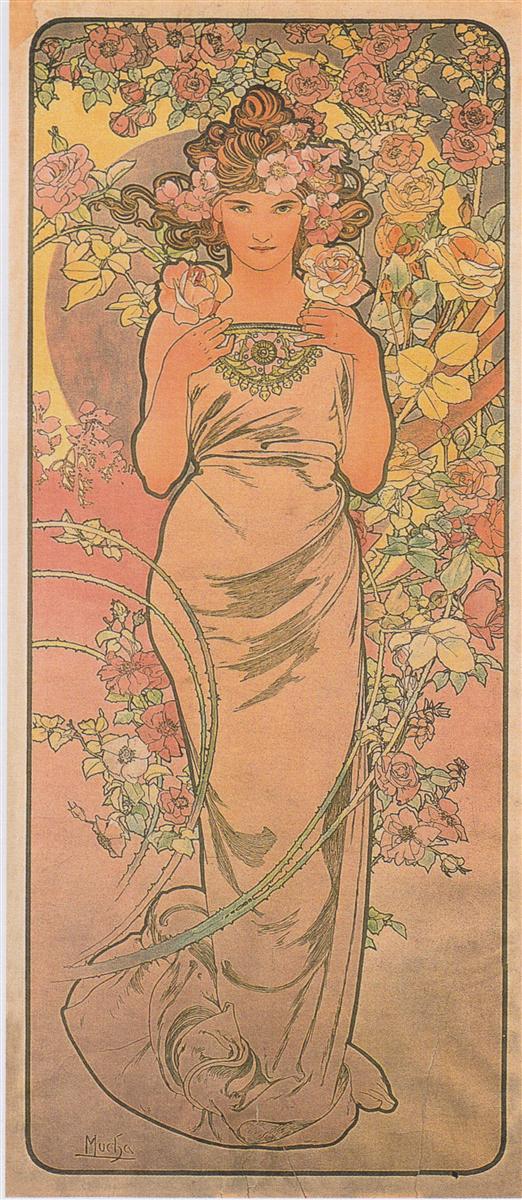

Alphonse Mucha’s “The Rose” (1898) turns a single flower into a complete climate. The tall, rounded panel presents a young woman standing frontally within a garden of roses, her body wrapped in pale drapery and her head circled by blossoms like a softly lit crown. A warm pink-to-gold atmosphere fills the field, while a few long thorny canes arc across the lower half like calligraphic strokes. The composition is at once decorative and emblematic: a human presence distilled from the character of a flower, meant to live on a wall and lend the room a continuous, tempered radiance.

A Flower Turned Personification

Mucha’s allegorical panels often translate abstract ideas—seasons, arts, stones—into poised female figures. In “The Rose,” the personification is unusually direct. The woman does not simply hold roses; she is rose-like in attitude and construction. Her expression is calm, her posture upright, her presence generous rather than insistent. Every element supports the identity: the floral diadem, the paired blossoms at her shoulders, the thorned stems that cross her dress, and the surrounding hedge of blooms. The panel suggests not the fleeting romance of a single flower but the steady, cultivated grace of a rose garden in full health.

Composition and Architectural Frame

The sheet is a tall rectangle with softly rounded corners, a format Mucha used to harmonize with domestic architecture. Within this frame the figure stands near life-size, centered along a vertical axis. A faint disk behind her head works as a halo and a compositional anchor, its curve echoed by the rounded top of the panel and by the arcs of the thorny canes below. The figure’s feet and pooled hem establish a firm base, while the roses rise to either side, balancing the symmetry without making it rigid. The border’s thin black fillet encloses the image like a mount for a cameo, turning the picture into an object rather than a mere scene.

The Palette and Atmospheric Gradient

Color is the panel’s mood engine. Mucha bathes the field in a warm gradient that moves from rosy pinks and apricots to mellow golds and pale olives. The drapery is not stark white but a soft cream that receives the ambient hue. Leaves are tipped with yellow rather than cold green, and shadows keep to a warm gray-brown. The effect is a late-afternoon glow, as if the entire garden were lit by a slanting sun that warms rather than dazzles. This palette keeps the panel kind to interiors, allowing it to cast a gentle light in a room regardless of actual illumination.

The Rose as Language

The rose carries centuries of cultural meaning—love, beauty, transience, devotion—but Mucha’s treatment is neither moralizing nor sentimental. The blossoms cluster around the head to form a floral halo, elevating the figure without separating her from the natural world. The paired roses she lifts near the ornate necklace feel like an offering to herself, a moment of delighted acknowledgment rather than display. The rose becomes a language of measured pleasure, suggesting cultivation and care rather than excess. Even the abundant background reads as tended rather than wild, an orderly bouquet translated into architecture.

The Halo and the Face

A muted circular disk behind the head concentrates attention without theatrical glare. It has the quiet authority of a fresco nimbus, adapted to the decorative register of a poster. The face it frames is direct and lucid: the eyes meet the viewer without challenge; the mouth rests between smile and thought. In Mucha’s work the face decides the tone. Here it keeps the profusion of floral detail from turning cloying, holding the whole in a state of poised warmth.

The Thorn and Tension

One of the design’s masterstrokes is the use of thorny canes as compositional lines. They sweep across the lower half in elegant arcs, their pricked edges delicately indicated. These lines perform two roles. They prevent the drapery from becoming a continuous vertical mass by introducing supple diagonals, and they insert a hint of tension into the idyll. A rose is beauty guarded; its defense is part of its form. The panel acknowledges that truth without breaking its serenity, letting the viewer feel grace and caution together.

Drapery and Body Language

Mucha renders the dress with a draughtsman’s economy: a black keyline defines edges and folds, soft washes supply volume, and the paper’s own light serves as highlight. The fabric wraps the body like a column, pinching slightly at the waist and pooling in rounded folds at the feet. The figure’s bare toes peep from the hem, a small detail that grounds the allegory in human presence. Because the drapery falls in long, uninterrupted paths, it reads as time made visible—a slow, continuous descent that mirrors the patience of cultivation.

Hair as Ornamental Current

The hair, gathered high and threaded with blossoms, unspools in controlled curls that echo the vines around her. It acts as a dark counterpoint to the pale drapery and as a network of lines that move the eye from face to shoulders to the surrounding flora. Mucha’s line modulates along each strand, thickening at turns and thinning across lengths so that the hair retains life without heavy modeling. The coiffure’s symmetry underscores the panel’s calm, while the few wandering curls lend it breath.

The Necklace as Solar Heart

At the center of the chest hangs an elaborate necklace built from concentric circles and pendant drops. It functions as a visual sun within the composition: a compact, radiant structure that gathers the surrounding forms. Its geometry contrasts with the organic irregularity of leaves and petals, and its cool green stones temper the field’s warmth. The necklace also suggests the rose’s inner architecture—the spiral of the center and the ring of outer petals—translated into ornament. By lifting the paired roses near this jewelry, the figure equates body, ornament, and flower in a single gesture.

Botany as Pattern

Mucha’s background roses are recognizable but stylized, their petal stacks simplified into crisp silhouettes and pale washes. He arranges them not as a natural hedge but as a repeating tapestry that supports the central figure. Leaves stream in the same whiplash rhythm that shapes the hair and the thorn canes, binding everything to a common tempo. The result is a surface that can be read both as garden and as decorative fabric, a typical Mucha fusion of nature and design.

Lithographic Technique and Paper Glow

“The Rose” relies on the strengths of color lithography: a crisp black keyline, transparent color layers, and the luminous contribution of the paper itself. Highlights across petals, cheeks, and drapery are often reserves of bare paper, which read as living light rather than paint. Broad color areas—especially the pink-gold ground—show a granular texture from crayon on the lithographic stone, keeping the surface lively and forgiving to minor registration shifts. These decisions also make the image durable in reproduction; even later impressions or posters that have mellowed with age retain the essential glow.

Dialogues with Earlier Florals

Compared with Mucha’s 1897 “Rose,” this 1898 panel feels more atmospheric and less architectural. The earlier work is all honey and cream; this one is suffused with pink twilight. In both, thorn canes cross the drapery and a floral halo crowns the face, but the later sheet lets color carry more of the mood while keeping the line slightly lighter. Set alongside “Lily,” “Iris,” or “Carnation,” “The Rose” reads as the most maternal and centered of the group—the flower that embraces abundance and sets the key for the rest.

Japonisme and Decorative Synthesis

The panel’s flattened space and patterned background reveal the era’s admiration for Japanese woodblock prints. Rather than attempting atmospheric perspective, Mucha stacks motifs across the surface, allowing the repetition of shapes and the modulation of color to suggest depth. The single circular halo behind the head functions like a rising moon from a ukiyo-e landscape, yet it is absorbed into a European allegorical vocabulary. This synthesis—Japan’s graphic clarity married to Europe’s emblematic tradition—was a cornerstone of Mucha’s language.

The Viewer’s Journey Through the Image

The design guides the eye with the ease of a well-laid garden path. Most viewers begin at the face, move to the paired roses and necklace, glide down the long fall of drapery to the hem, then follow the thorn canes back upward into the rose thicket. The rounded corners and thin inner border return attention to the center, where the halo catches it and offers the face again. This slow circuit can repeat indefinitely without fatigue, which is exactly what a domestic panel must allow: a patient rhythm that rewards daily glances.

Domestic Function and Social Context

Mucha intended panels like “The Rose” to grace apartments, cafés, and studios, where they would live as companions rather than as events. Their scale, palettes, and subjects were chosen with such interiors in mind. The rose was not merely a symbol but a promise of civilized pleasure—gardens, conversation, perfume, the care of things. In late nineteenth-century Paris, where modern life accelerated while interiors grew more curated, such images offered a counterweight: a sense that beauty could be an everyday practice.

Ornament that Organizes rather than Clutters

One reason the panel still feels fresh is that its profusion is disciplined. Every ornamental part has a job. The halo secures the head; the canes stabilize the lower half; the background tapestry keeps the central column from floating; the border arrests the eye before it leaks into the wall. The viewer experiences a full, generous surface that never becomes noisy, a balance designers continue to study.

Enduring Appeal and Afterlife

“The Rose” remains one of Mucha’s most reproduced images because it is both specific and flexible. Its mood of warm poise suits many spaces; its palette flatters a wide range of furnishings; its allegory is legible without being didactic. The panel translates readily to textiles, ceramics, and book covers because its forms are graphic yet gracious. Contemporary visual culture—fashion editorials framed with floral halos, packaging that pairs warm gradients with crisp line—still borrows from this grammar.

Conclusion

“The Rose” gathers many of Alphonse Mucha’s strengths into a single, welcoming image. A clear vertical composition, a face that sets a calm tone, hair and stems that write supple lines across the surface, a palette that glows from within, and an allegory carried by gesture rather than explanation—together they shape a panel that feels inevitable. The rose becomes not an emblem of feverish romance but of cultivated abundance and steadiness. More than a century later, the figure stands where she began, offering the room not a command but a climate, and doing so with the patience of a well-tended garden.