Image source: wikiart.org

Setting the Scene and the Moment in Matisse’s Career

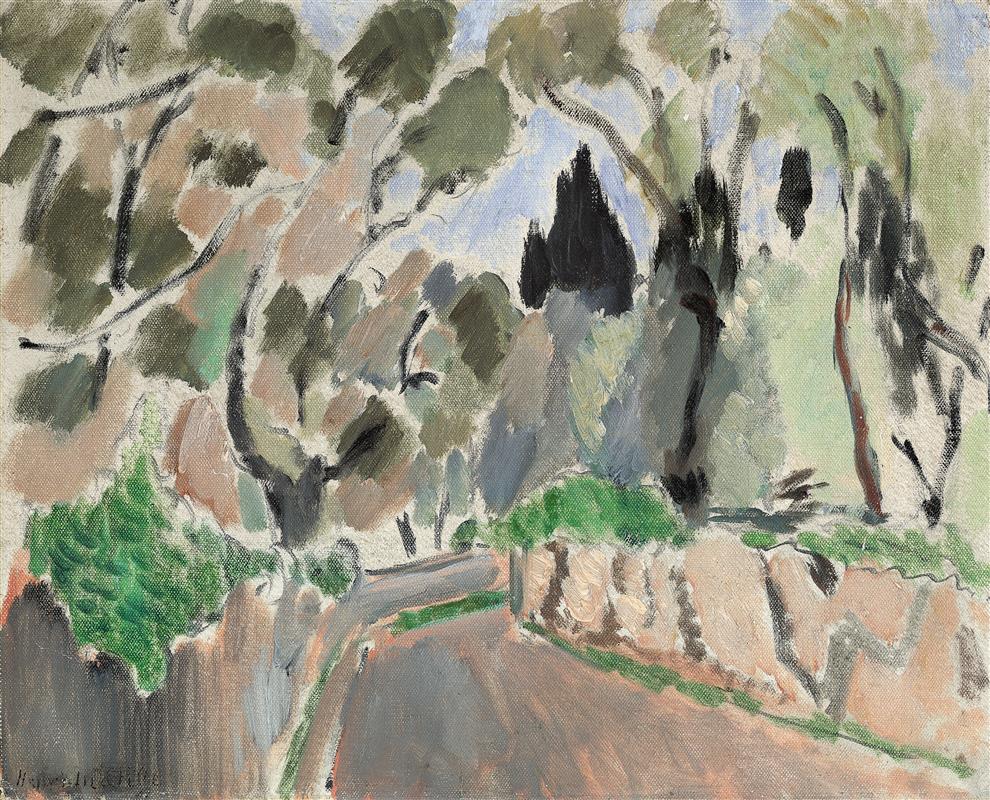

Painted in 1918, “The Road” belongs to the first year of Henri Matisse’s long engagement with the light and atmosphere of the French Riviera. After the blazing chromatic clashes of Fauvism and a decade of more austere exploration, the Nice years opened with a change of temperature rather than a change of heart. Matisse kept his belief that line and color could carry the full burden of expression, but he tuned them to a climate of clarity and calm. “The Road” captures that recalibration in a small, dense landscape: a curving lane edged by stone walls, trees tossed by a sea breeze, a high, milky-blue sky that keeps the horizon close. The scene is not a postcard; it is a pulse of place, recorded through economical means and visible brushwork that reads like the trace of breathing.

Composition: A Curve that Organizes the World

The painting is built around a single, persuasive gesture—the road’s curve. Entering from the bottom edge, the lane arcs left, slips behind a hedge, and disappears into tangled foliage. That curve is more than a route; it is the organizing rhythm of the whole. Branches bend in sympathy; the stone walls angle forward and recede in staggered planes; masses of foliage collect and disperse across the canvas in counterphrases. Rather than a central focus, Matisse gives us a path, an invitation to move. The eye learns the picture by walking it, and while it walks it discovers how the verticals of tree trunks counterweight the lane’s lateral sweep, how the triangular wedge of a cypress steadies the looseness of surrounding brush, and how the high sky presses gently downward to hold everything near the surface.

The Palette: Riviera Air in Measured Harmonies

Color here is Mediterranean but moderated. The sky is a pale, slightly chalked blue; the foliage ranges from olive and bottle green to silvery eucalyptus tones; the stone embankments register as warm sandstone and beige; the road itself is laid in earthen pinks and cool grays. These hues are not neutral; they are tuned. Matisse lets cool and warm neighbors quietly activate each other—green made livelier by a blush of ochre beneath, a lavender-gray shadow cooling an adjacent buff wall, a pale turquoise glint slipping through a tree’s canopy to suggest reflected sky. Because he avoids saturated clashes, the scene glows without glare. Color becomes climate: dry air, high light, shadows that are cool but not heavy.

Black as a Positive Color and the Calligraphy of Trunks

One of Matisse’s most powerful tools is black used not as absence but as presence. In “The Road,” the trunks and some branches are drawn as broad, black strokes laid with a loaded brush. Far from flattening the image, these strokes are structural beams that hold the painting together. They read as calligraphy: gestures with beginnings, middles, and tapering ends, set at varying angles that give the grove its swaying rhythm. Where black meets sky, it gleams; where it crosses foliage, it intensifies the surrounding green; where it accents the stone wall, it clarifies plane changes with swift economy. The drawing does not imprison color; it conducts it like a musical staff.

Brushwork: The Truth of the Stroke

The surface declares the process. Leaves appear as short, angled dabs that catch light on their ridges; thin, scumbled strokes allow the canvas weave to breathe through pale passages of sky and wall; thicker, more elastic sweeps construct the road’s curve and the broader tree trunks. Nowhere does Matisse smooth the paint to a cosmetic finish. The visible stroke is not bravura for its own sake but the record of seeing. The viewer recognizes the tempo change from canopy to wall to road, and that temporal experience—slow in one zone, quick in another—becomes part of the painting’s meaning.

Space: Nearness Held to the Surface

Depth in the painting is convincing yet restrained. Overlaps and value shifts do the heavy lifting: darker, sharper accents for the nearest trees; softened edges and cooler notes for forms that recede. The horizon itself is more implied than drawn, glimpsed through gaps in foliage as a wedge of pale sky and a breath of distance. Yet Matisse keeps the space shallow by stacking planes close to the picture surface and by allowing the stone wall on the right to push forward like a stage wing. The result is a landscape you can enter imaginatively while still experiencing it as a woven design of shapes and colors on a flat rectangle.

The Road as Motif and Metaphor

Roads in painting often function as narrative devices, promising arrival or departure. Matisse’s road is different. It does not lead to a picturesque church or a sunlit village; it disappears into trees. Its purpose is formal and experiential. Formally, it supplies the long curve that organizes counter-motions across the canvas. Experientially, it proposes a way of looking that is sequential and attentive: step, pause, notice a branch, notice a wall, notice a patch of light, then step again. The motif thus becomes a metaphor for attention itself—art as a path made by walking.

Weather and the Idea of Climate

The picture contains no theatrical weather event—no gust bending trees to breaking, no raking sunlight, no storm-front drama. Instead it records climate: the constant conditions that define a place. The sky’s paleness, the dry pinks of the road, the silvery greens of leaves all speak of the Riviera’s clarity. Shadows are cool but not cold; colors hold their pitch even where light thins. This attention to climate rather than episodic weather is part of the painting’s serenity. It does not impress you with a moment; it convinces you of a world.

Dialogues with Cézanne, Japanese Prints, and Matisse’s Own Past

Matisse’s landscape language is never isolated from tradition. From Cézanne he learned to build volume from color planes and to allow nature to be reorganized into constructive units. In “The Road,” stone walls become interlocking blocks, the road a banded ramp, foliage a series of faceted notes rather than blended mush. At the same time, the calligraphic blacks and the cropping that pushes trunks against the picture’s edges speak to his admiration for Japanese prints, where silhouettes and arabesques carry as much force as modeled forms. Compared with the Fauvist canvases from a decade earlier, the chroma is gentler, the drawing more controlled, the atmosphere steadier. Yet the belief that a few decisive relationships can reveal the whole remains the same.

The Intelligence of Omission

Much of the painting’s vitality comes from what Matisse chooses not to describe. Leaves are clusters of strokes, not specimens; stones are planes with quick, dark accents for joints; the road’s surface is a sweep of color whose ruts and patches are suggested with minimal marks. These omissions concentrate the viewer’s attention on interval and rhythm—the spaces between trees, the run of wall segments, the alternation of light and shadow across the lane. Negative space becomes a positive actor; the unpainted or lightly painted canvas glows through, providing a dry light that suits the subject.

Psychological Weather: Calm Without Stasis

Despite its composure, the picture carries a quiet psychological charge. The curve of the road invites motion; the leaning trunks and tossed canopies suggest a breeze; the high sky opens the breathing space above. Yet the palette’s moderation and the measured pace of strokes keep the mood from tipping into agitation. The painting feels thoughtful, collected. In 1918, that feeling mattered. As Europe emerged from war, Matisse’s turn to balanced, breathable compositions can be read as an ethic as much as an aesthetic: clarity as a way of life.

How to Look: A Suggested Circuit Through the Picture

Begin at the lower right where the pink road meets the shadowed verge. Follow the road’s cool gray spine as it curves left and vanishes behind the hedge. Let your eye climb the nearest black trunk and watch it fork into angled branches that push through olive and sage canopies. Cross to the cypress wedge, then drift into the pale blue deposits of sky that stripe the top between foliage masses. Return down the stone wall, noting quick, dark seams that state its construction, and step back onto the road. That circuit—lane to trunk to sky to wall to lane—mirrors the painting’s internal rhythm and reveals how each passage answers another across the surface.

Material Presence and Evidence of Revision

Look closely and you’ll find pentimenti—soft halos where branches were adjusted, edges where a sky color was dragged over earlier foliage, seams where the wall’s top was clarified after the road’s curve was set. These traces of change are not incidental. They show that the final balance was achieved through testing and correction, that inevitability is something earned. The picture’s calm depends on that labor, and the visible record of it invites respect rather than awe.

Relationship to Matisse’s Other 1918 Landscapes

“The Road” converses fruitfully with other landscapes Matisse painted around Nice in the same year. Works such as “Large Landscape with Trees” emphasize stratified bands—sky, hills, orchard—held in a cool key; others, like “Landscape around Nice,” immerse the viewer in dense groves with glimpses of sea. “The Road” sits between those modes. It offers immersion but also a clear organizing armature in the road’s curve; it tempers color yet maintains the sensuality of brush against leaf and stone. Seen together, these canvases map Matisse’s evolving vocabulary for the South: a grammar flexible enough to express both structural calm and tactile immediacy.

Why the Painting Feels Contemporary

A century on, “The Road” looks strikingly fresh. Its reduced palette and big shape language read at a glance; its gestural lines reward close viewing; its shallow space anticipates modern design’s love of surface while retaining the credibility of observed depth. In a visual culture that values both clarity and the trace of making, Matisse’s combination—firm composition plus honest brushwork—feels entirely of the moment. The painting shows how restraint can amplify impact and how a few well-chosen relations can stand in for the world.

The Road as an Ethics of Attention

Beyond its formal achievements, the painting proposes a way to look at the world. The road is not spectacular, the trees are not unique, and the sky is ordinary. Yet by attending to the curve’s rhythm, to the counter-sway of branches, to the precise tuning of greens and grays, Matisse makes the ordinary inexhaustible. The work suggests that the discipline of noticing—of following the path with patience—can transform familiar scenery into a site of renewal. That suggestion may be the painting’s most lasting gift.

Conclusion: A Curve, a Breeze, and a Calm Resolve

“The Road” compresses the beginnings of Matisse’s Nice period into one poised statement. A single curve organizes the composition; black calligraphy sets the beat; moderated color breathes Mediterranean air; visible strokes keep the surface alive. Nothing is extraneous, and everything contributes to a mood of collected movement—calm without stasis, clarity without chill. In 1918 the painting announced that Matisse had found a climate, literal and artistic, in which balance could flourish. Today it still shows how a path, a wall, a few trees, and a high sky can, in the right hands, become a complete world.