Image source: wikiart.org

A Room Composed Around Red

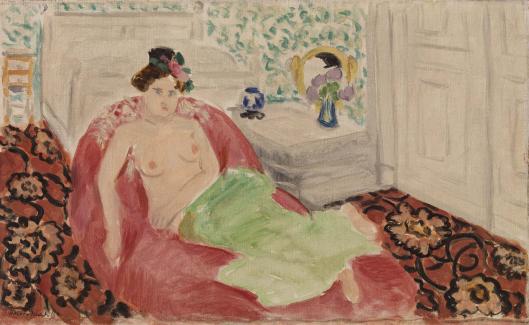

Henri Matisse’s “The Red Couch” (1920) is an interior staged with the clarity and calm that define his Nice period. A model reclines across a crimson couch, her torso bare and her hips wrapped in a cool green cloth. The floor blooms with a dark, floral carpet; a patterned wall flickers with small green leaves; a bedside table carries a vase and a round mirror whose bright rim turns the back of the room into a secondary picture. Nothing here is extravagant in detail, yet the painting feels abundant because every plane of color is placed to do structural work. Red is not only a hue; it is an architecture that anchors the figure, moderates the surrounding patterns, and sets the emotional temperature of the scene.

The Nice Period and a New Grammar of Ease

After the First World War, Matisse shifted his practice to the sun-lit interiors of Nice. There he pursued a slower grammar: large, legible shapes; simplified drawing; and color pitched to the room’s even Mediterranean light. “The Red Couch” stands at the start of this sustained exploration of interiors, models, and textiles—a prelude to the odalisque sequence that would occupy much of the decade. In place of avant-garde turbulence he sought stability and generosity. The modernity of these pictures lies in the discipline of their means: how a few fields of paint, tuned as relationships of value and temperature, can carry the feeling of an inhabited space.

Composition as a Conversation of Curves and Rectangles

The canvas organizes itself through a dialogue between curving forms and sober planes. The couch sweeps in a slow arc, a red cradle that lifts the model’s torso and bears her along the diagonal toward the table. Against that arc, a procession of rectangles—door, wall panel, headboard, and tabletop—states the room’s geometry. The oval mirror repeats the couch’s curve in a smaller key, creating an upper counterweight to the large field of red below. The figure’s body, bent at hip and elbow, participates in both families of shape: soft curves at the shoulder and thigh, crisp angles where forearm meets torso and where the green drapery folds. This interplay carries the eye in a circuit: face to mirror, mirror to table, table to carpet’s motifs, carpet back to the red arc and the figure.

The Red Couch as Engine of the Picture

Matisse lets the couch do heavy work. Its saturated crimson locks the foreground in place and flattens depth just enough to keep the viewer aware of the picture plane. Where the fabric would crease or catch the light, he slightly cools or warms the red so that the surface breathes rather than becoming a single decorative slab. The entire palette calibrates against this red. Skin notes adopt honey and rose, the green of the wrap arrives as a cooling counter-tone, and the pale architecture of door and headboard steadies the heat. The couch is not simply where the model rests; it is the engine that sets the register for everything else.

Pattern as Structure, Not Ornament

Matisse’s patterns do not operate as afterthoughts. The carpet’s large rosettes, painted in a deep brown-black with yellow centers, are spaced like beats in a measure, slowing the eye’s travel across the floor and keeping the red couch from sliding too easily forward. The wall’s small green sprigs hover between decoration and air, thinning toward the top so that the room keeps its lightness. Pattern here clarifies distances: big blooms under the couch state nearness; tiny leaves behind the table state recession; the mirror’s bright rim announces a plane lifted from the wall. With only a few signs, the painter conjures a complete interior climate.

A Mirror That Lights the Room

The round mirror does not deliver a literal reflection of the model; it catches brightness and a abbreviated black profile accented by a spray of violets. In many Nice interiors Matisse uses mirrors to redirect the eye and to add a secondary light source. Here the gold rim becomes a small sun that balances the large red mass. The mirror’s elliptical highlight, together with the white of the table linen and the faint glint on a blue vase, forms a chain of cool radiances that temper the warmth of the couch and carpet. The device keeps the composition open at the top right, preventing the red from monopolizing the scene.

Drawing Reduced to Essential Signs

Matisse’s drawing is a lesson in economy. The model’s features are stated with a few decisive accents: a dark wedge for the eye, a small turn of the mouth, a measured contour around cheek and chin. Hands are simplified almost to silhouettes; toes and knee are barely notated; the breast is modeled with a couple of modulated strokes rather than with cast shadow. These abbreviations are not evasions. They clear space for color to carry volume and for placement to carry meaning. The figure’s attitude—alert yet at ease—arrives because the contour lines are so sure that no excess description is needed.

Color Intervals That Set Mood

The painting’s emotion rides on intervals among three principal fields: the couch’s crimson, the carpet’s very dark red-brown, and the green wrap. Between them Matisse threads mid-tones—the pinks and creams of skin, the off-whites of wall and door, the pale gray of the headboard. The result is warmth held in balance. Crimson and brown establish a low, resonant chord; the cool green and scattered blues add fresh overtones; the whites and creams keep the chord from turning heavy. Because color here takes the place of strong shadow, the scene feels luminous even though the values are moderate. It is more like a room filled with air than a stage set with spotlights.

Space Without Theatrical Illusion

Depth in “The Red Couch” is stated sparingly. The table is a stacked set of shapes, the door a quiet slab, the headboard a single block. The carpet is not tilted aggressively; it reads as a patterned plane sliding gently under the couch. This discipline acknowledges the physical fact of paint on canvas. Matisse does not ask the image to become a window. Instead he keeps two truths in play: the room recedes, and the painting remains a surface. The coexistence of those truths, held without strain, is a signature of his mature classicism.

The Figure as Hinge Between Domestic and Exotic

Contemporary viewers compared Matisse’s Nice interiors to odalisque scenes, and “The Red Couch” indeed anticipates that theme: a partially draped model, a wealth of textiles, and a vegetal wallpaper that hints at garden or screen. Yet the tone here remains domestic rather than theatrical. The model is present as a person, not a cipher. Her sidelong glance is level, neither coy nor defiant. The green wrap reads as a practical cloth rather than tableau costume. If the room nods to the history of Orientalist interiors—from Ingres to late-nineteenth-century studio props—it does so to expand color and pattern possibilities, not to stage fantasy. The painting’s ethics are the ethics of attention: dignity through clarity and placement rather than through narrative pose.

Rhythm of the Body and the Room

One of the painting’s quiet achievements is the way bodily rhythm and room rhythm interlock. The diagonal from shoulder to hip echoes the couch’s slope; the bent elbow repeats the small right-angle steps in the table’s drawer and the door’s panels; the curve of the thigh answers the round mirror. Nothing locks into a strict symmetry, yet everything finds a partner. Because of this web of rhymes, the model appears truly in the room rather than pasted upon it. She is another shape among shapes, granted distinction not by contour alone but by a chorus of agreements.

Material Surface and the Sensation of Touch

The painting rewards close viewing. The couch’s red is laid in thin, responsive layers, so the ground tint participates in the final hue. The carpet motifs carry slightly thicker paste, catching real light and giving the floor a tactile presence. The green wrap is brushed with longer, united strokes that let the cloth feel smooth and cool; the wall’s pattern is dabbed in quick, leafy touches that keep it buoyant. Matisse turns material differences—thinness versus thickness, drag versus glide—into analogues of texture: velvet, pile, linen, plaster. The eye senses what each thing would feel like in the hand.

The Social World Hinted but Uninsisted

Objects on the table—a vase, perhaps a perfume bottle, a bouquet—suggest habits of care and arrangement, but the painting declines anecdote. There is no narrative beyond the sustained mood of rest and alertness. That decision keeps the picture in the realm Matisse prefers: not storytelling but composing. The social world is present as a set of traces—chosen textiles, tended flowers, the comfort of a familiar couch—registered through color rather than summarized in symbols.

Relation to Earlier Domestic Painters

The painting converses with Bonnard and Vuillard, who also celebrated patterned rooms and intimate scale. Where Bonnard submerges form into a bath of color and Vuillard wraps figures in wallpapered density, Matisse clarifies. He removes clutter, stabilizes the armature, and lets the room’s few actors—couch, carpet, wall, table, figure—play clear roles. That restraint is why the image reads instantly from across a room and continues to unfold at close range. It is also why such interiors remain fresh: they are built on relations rather than on period décor alone.

The Light of Work, Not Spectacle

The illumination is steady and diffused, as if from a high window out of frame. Under such light, color finds its natural pitch and edges do not lie. The model can be painted with minimal modeling; the couch can hold its field without turning flat; the carpet can sustain darks without swallowing nearby forms. Matisse consistently sought this kind of weather for his interiors because it serves the honesty of his enterprise. The painting is a record of work done in a room, not a set lit for an audience.

The Viewer’s Role: A Calm Participation

The painting positions the viewer at a respectful distance, slightly above the couch’s level but not toweringly so. We are close enough to enter the rhythm of shapes and to read the model’s expression, yet far enough that the room’s geometry stays legible. The gaze becomes a kind of participation in the painter’s choices. We follow the same circuits he designed—red arc, green cloth, mirror rim, table white—and in doing so we experience the serenity those circuits were meant to keep.

Why the Picture Still Feels Present

A century on, “The Red Couch” retains its authority because it embodies a paradox that modern painting prizes: simplicity that contains complexity. With a handful of forms and a restrained palette, Matisse captures the feel of a room where comfort, attention, and color coexist. The picture does not demand emotion; it provides conditions in which a viewer’s attention can rest. That quality—sustained, lucid rest—is rare in any era and explains the painting’s continual ability to welcome new eyes.

Conclusion: A Civilization of Placement

At heart, this canvas is an argument for placement. The red couch anchors, the carpet grounds, the wall breathes, the mirror brightens, and the figure—poised between alertness and repose—knits the parts into a single, walk-in sentence. What might have been merely decorative becomes architectural because each color plane is necessary to the others. “The Red Couch” shows how a painter can make dignity out of ordinary rooms and calm out of strong color, and how attention, steadily practiced, can turn pattern and furniture into a way of thinking.