Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

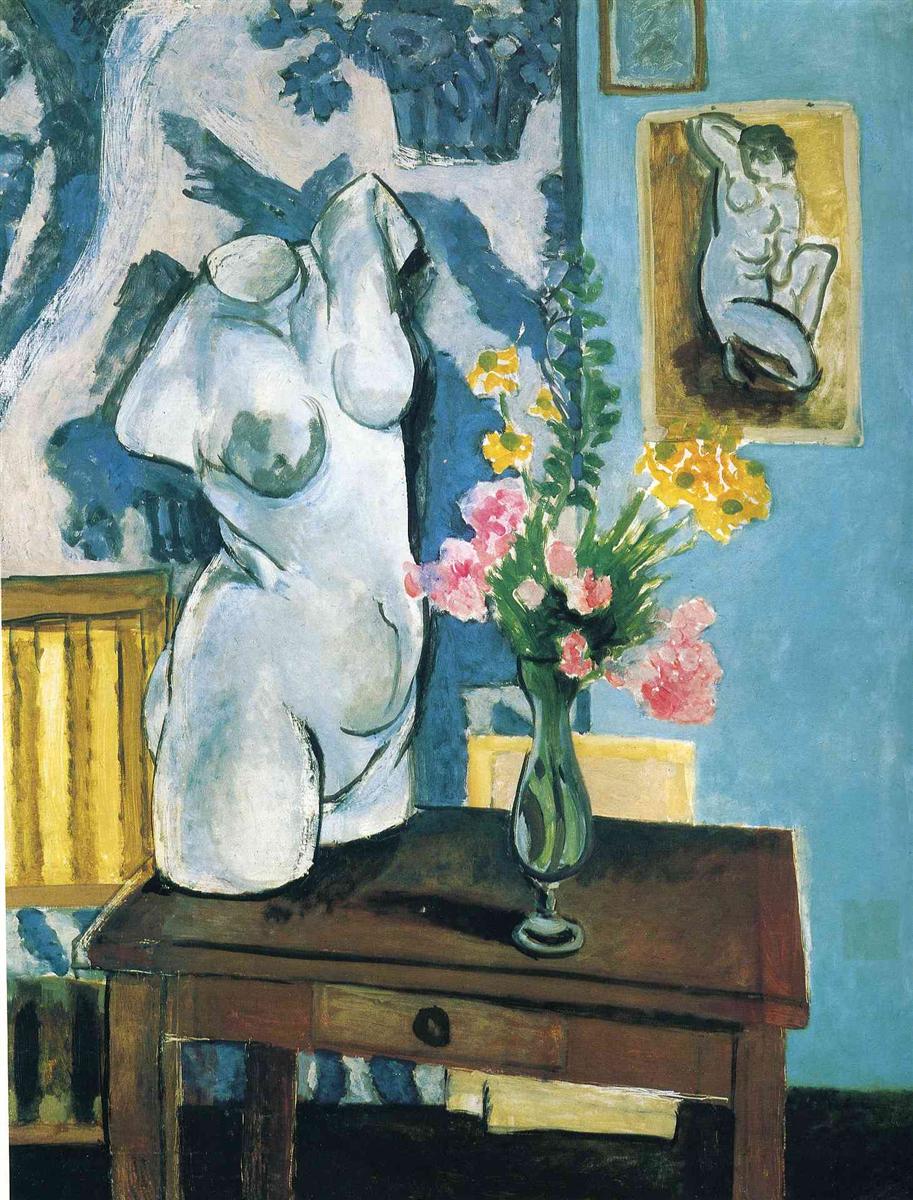

Henri Matisse’s “The Plaster Torso” (1919) turns a familiar studio corner—cast sculpture on a worktable, bouquet in a glass vase, patterned wall, framed relief—into a complete architecture of color, rhythm, and thought. A headless white torso swells like a compact moon against blue arabesques. A lean green vase holds pink and yellow blossoms that lift into the same air the torso inhabits. A modest wooden table anchors the scene; behind it, rectangles of pale yellow and sea blue stack like cards, and on the right a small framed relief of a kneeling nude repeats the larger figure’s pose. Everywhere, the painting braids three kinds of image—object, decoration, and depiction of art—so the viewer experiences a studio that thinks about itself while remaining sensuously alive.

The Nice Period Aftermath

Painted in the first years of Matisse’s Nice period, the work reveals his postwar conviction that stability and lucidity could be more radical than shock. In Nice he returned to interiors, staged with patterned walls, small tables, mirrors, shutters, and a measured Mediterranean light. Decoration became structure; pattern held the space; color carried the emotional climate. “The Plaster Torso” fits that ethic precisely but adds a twist: sculpture takes center stage. The cast is not a relic of academic training; it is a tool for modern composition, a carrier of white light and a generator of rhythmic contour that activates everything around it.

First Impressions and Motif

A white torso sits left of center on a dark tabletop. The body has no head or arms, only a strong twist through the chest and a powerful slope from shoulder to hip. It reads as both monument and fragment, a vessel for light and a record of carving. To the right stands a slim glass vase filled with carnations and wild sprays of yellow; their stems ride the vase’s throat like green calligraphy. The wall behind breaks into two distinct fields: at left a patterned ground of layered blues and whites, at right a calmer expanse of sky blue interrupted by small framed rectangles. Among those rectangles, a golden plaque holds a relief of a nude with an arm curved over the head, echoing in miniature the torso’s rise. Color blocks—cool blues, pale yellows—peek behind the table like paper pinned to a studio wall. The entire surface is a play between curving bodies and squared supports, between white sculptural mass and chromatic atmosphere.

A Composition Built on Counterweights

The design hinges on counterweights. The torso’s heavy, luminous mass presses the left side down. Matisse balances it with a vertical bouquet on the right, whose clustered blossoms create a lighter, airy mass that rises as the torso sinks. The table provides a stable earth, its single drawer and dark top drawing the scattered elements into one plane. The small rectangles on the wall—frame, plaque, and color blocks—stiffen the right half and keep the tall vase from seeming precarious. The left wall’s blue arabesques act like a woven curtain, a patterned air in which the torso hovers. Every element answers another: curve meets straight, weight meets buoyancy, whiteness meets color.

The Torso as Actor and Idea

Matisse’s plaster cast is not merely a studio prop. It is an argument about what figure can be in a modern interior. Without head or limbs, identity dissolves into rhythm: the swoop of the upper chest, the lift of the left shoulder stump, the gentle compression at the waist. The torso’s whites are not uniform; they shift from cool to warm, picking up blues from the wall and browns from the table, so the sculpture becomes a prism for the room’s climate. Its contour is alive—a dark line fattens where mass turns away, thins where light slips over the edge. In Nice, Matisse often asked pattern to act like architecture; here, he asks sculpture to perform the same duty. The torso secures the room, holds its light, and orders its rhythms.

Painting in Dialogue with Sculpture

Across the canvas Matisse stages a conversation between media. The torso offers volume and silence; the flowers answer with color and ephemeral life. The relief on the right converts sculpture back into drawing, its incised lines and shallow modeling reading like a charcoal sketch in gold. The wallpaper pattern, with its foliate whorls, flirts with low-relief sculpture as well; it is a field of embossed-looking forms that nearly share the torso’s whiteness. The result is a studio ecology in which objects are constantly translated: sculpture becomes silhouette and light; flowers become pattern; pattern behaves like carving; carved relief returns to line. You feel the painter thinking aloud through things.

Color Architecture and Temperature

Color keeps the entire construction legible. Two big families dominate. The first is the cool register: Prussian and ultramarine blues in the patterned wall; a gentler sky blue on the right; the greenish glass of the vase; the chilled whites of the cast. The second family is warm: honey ochres in the wall plaque and table rails; rosy pinks and sunny yellows in the flowers; a dark, earthy brown in the tabletop and drawer. Matisse distributes these families so the eye can travel without interruption. Warm accents gather around the vase and the relief, relieving the cool sea of blue; cooler notes echo in the torso’s shadows and within the bouquet’s leaves. Because each family repeats in several places, the painting reads as a single climate rather than a collage of corners.

Light and Atmosphere

Nice light is generous but not theatrical. Here it arrives as a steady bath that makes materials speak. The torso breathes with pale transitions; the table’s top glows softly rather than flashing; the vase collects vertical highlights that declare glass and hold the stems in suspension. Shadows are economical: a dark halo under the torso roots it on the table; the bouquet casts a slight smudge that stops the tabletop from floating into abstraction. The wall’s patterned left half is lighter than the right blue field, keeping the torso in front and giving the cooler expanse a sense of airy distance. Light in this room behaves like a patient teacher—never overwhelming, always clarifying.

The Table as Stage

Matisse often builds interiors around a single planar anchor—red lattice floors, tiled patios, heavy black tables. Here the brown tabletop serves as stage and horizon. It carries the weight of sculpture and the spring of blossoms without buckling. Its near edge is drawn cleanly; the far edge is slighter, letting the objects sit believably within space. The drawer, with a single round pull, is a modest note that humanizes the furniture and weighs the lower half. Under the top, a strip of pale paint suggests a slip of paper or a cloth tucked in the gap, a casual studio detail that prevents the table from becoming schematic.

The Bouquet as Counterpoint

If the torso is mass, the flowers are music. Pink heads cluster into chords; yellow tongues reach into the blue field behind them; upright green stems provide a trellis for small color beats. The bouquet’s placement is precise: just right of center, where it overlaps blue wall and ocher plaque, knitting the painting’s halves. The glass vase, taller than it is wide, repeats the torso’s vertical thrust but with translucency instead of opacity. The floral rhythm also echoes the wallpaper’s foliate swirls, translating the fixed decoration into living growth. Without the bouquet, the room would be austere; with it, the scene breathes.

Patterned Wall and Blue Field

The left wall is a tapestry of blue and white that behaves like a low-relief landscape—basket shapes, leafy silhouettes, and meandering bands that recall Matisse’s earlier Fauvist arabesques. It provides both context and cushion for the sculpture, as if the torso were seated in front of a garden of painted air. The right wall, by contrast, is a slab of simple blue. That sudden calm allows framed rectangles to read cleanly and gives receptors for the bouquet’s yellows and pinks. The meeting of patterned and plain is negotiated by small blocks of color—squares and rectangles like swatches—keeping the edge lively without fuss.

Framed Relief and Echo

On the right hangs a small, ocher-backed relief of a kneeling nude with an arm lifted behind the head. The pose mirrors the broken shoulders of the cast and turns the room into a chain of echoes: a sculptural gesture becomes a wall image that repeats in the bouquet’s upward stems. By shrinking the nude into a plaque, Matisse adjusts scale without changing the motif, proving that form—not size—generates coherence. Above the plaque a small framed rectangle, nearly empty, adds a high, cool note and balances the heavy table and cast below.

Drawing and the Living Contour

Matisse’s line is straightforward and responsive. The torso’s outline swells and thins, keeping anatomy from hardening into diagram. The table edges are clean but not mechanical; slight irregularities maintain the hand’s presence. The vase’s contour is beautifully economical—two quick S-curves that bulge and settle, crowned with a small oval at the foot. On the wall, the pattern’s whorls are written in loaded brush, giving the flat surface the vitality of handwriting. This living contour is crucial: it lets objects coexist with pattern without either one surrendering its identity.

Brushwork and Material Presence

Across the surface Matisse varies touch to match substance. The cast’s body is built with opaque, dragged strokes that leave grain and keep the white alive; the tabletop is swept with darker, broader passes; the glass vase receives vertical glints laid in one stroke each; the flowers are tapped and twisted with small, juicy deposits of paint. In the background he scumbles light blue over darker underlayers so that the wall feels like air, not masonry. You register paint as paint while believing in torso, wood, and glass, a balance that is the Nice period’s special gift.

Space: Shallow, Habitable, Designed

Depth is a matter of overlap and temperature. The torso overlaps the patterned wall and sits firmly on the table’s dark plane; the flowers overlap the blue field and the hanging plaque; the rectangles behind the table hover close to the surface like papers taped to a wall. There is no deep perspective, yet the space is walkable. You could step to the table, circle the cast, touch the cool glass. The painting stays a designed object even while hosting a plausible world.

Rhythm and the Viewer’s Path

The eye’s path is a repeatable loop. Many viewers start at the torso’s bright chest, slide down the waist to the table’s edge, step right along the drawer to the vase’s foot, rise through the green stem to the yellow and pink blossoms, skip to the ocher relief with its echoing pose, drift up to the small cool frame, and then cross left along the blue field to the patterned wall and back to the torso. With each lap, new rhymes surface: the green of the vase and the tiny green square in the lower right; the yellow blossoms and the ocher plaque; the torso’s cool shadows and the deep blues behind; the sculptural curve and the floral arc. Rhythm is how Matisse secures calm without stasis.

Meanings in a Studio Key

The painting can be read as a studio allegory. Sculpture, the enduring body, stands for permanence; flowers, for time’s passing and renewal; table, for work; wall, for imagination’s pattern; framed reliefs, for memory and precedent. But Matisse refuses heavy symbolism. He persuades through placement and relation. The studio becomes a place where different orders of form—carved, painted, grown—mutually illuminate each other. The message is practical and generous: art is made by making room for such conversations to occur.

Comparisons within 1919

Placed beside other 1919 canvases, “The Plaster Torso” offers concentrated intensity. Where “The Artist and his Model” stages a broader theater of work, this painting fixes on a corner and pushes relations to the edge. Where “The Bed in the Mirror” uses reflection to double space, here a relief duplicates the figure at a different scale. Where “The Black Table” uses a matte plane to choreograph color, the brown tabletop here stabilizes volume. Across them all runs the Nice grammar: a big anchoring plane, structural pattern, balanced warms and cools, and figures—human or sculptural—treated as chords within a decorative order.

Palette and Likely Materials

The surface points to a concise set of pigments handled opaquely with sparing translucence: lead white in the cast and high lights; ultramarine and Prussian blues in the patterned wall; cobalt and cerulean in the right-hand field; viridian or chromium oxide green for the vase and leaf tints; yellow ochre and raw sienna for plaque, table rails, and warm accents; alizarin crimson and cadmium red for pink blossoms adjusted with white; cadmium yellow in the bright flower heads; ivory black used lightly in shadows and to firm contours. The general opacity of color preserves the painting’s structural clarity; glazes are minimal, reserved for softening transitions.

How to Look

Approach the painting first as large shapes—the white mass of the torso, the brown table plane, the twin blue fields—and let the bouquet register as a bright hinge between them. Step closer and count how few strokes build the glass vase; notice the subtle greens inside the torso’s shadows; trace the edge where cast meets patterned wall and see how the contour breathes. Step back until the wall’s swirls and the flowers’ petals fuse into a single decorative hum. Repeat the loop from torso to vase to plaque to wall and home again. With each circuit, the studio’s order will feel more inevitable.

Conclusion

“The Plaster Torso” distills Matisse’s Nice-period intelligence into a room small enough to hold in a glance and rich enough to explore for hours. A fragment of sculpture becomes a full protagonist; a bouquet counterbalances mass with color; pattern becomes architecture; framed reliefs and color swatches articulate a thinking studio. The atmosphere is calm, but the decisions are daring: white against blue, curve against plane, object against ornament, permanence against bloom. Matisse shows how a painter can make a world by allowing different kinds of form to converse—quietly, precisely, and with inexhaustible grace.