Image source: wikiart.org

Historical Context And The Nice-Period Return To Open Air

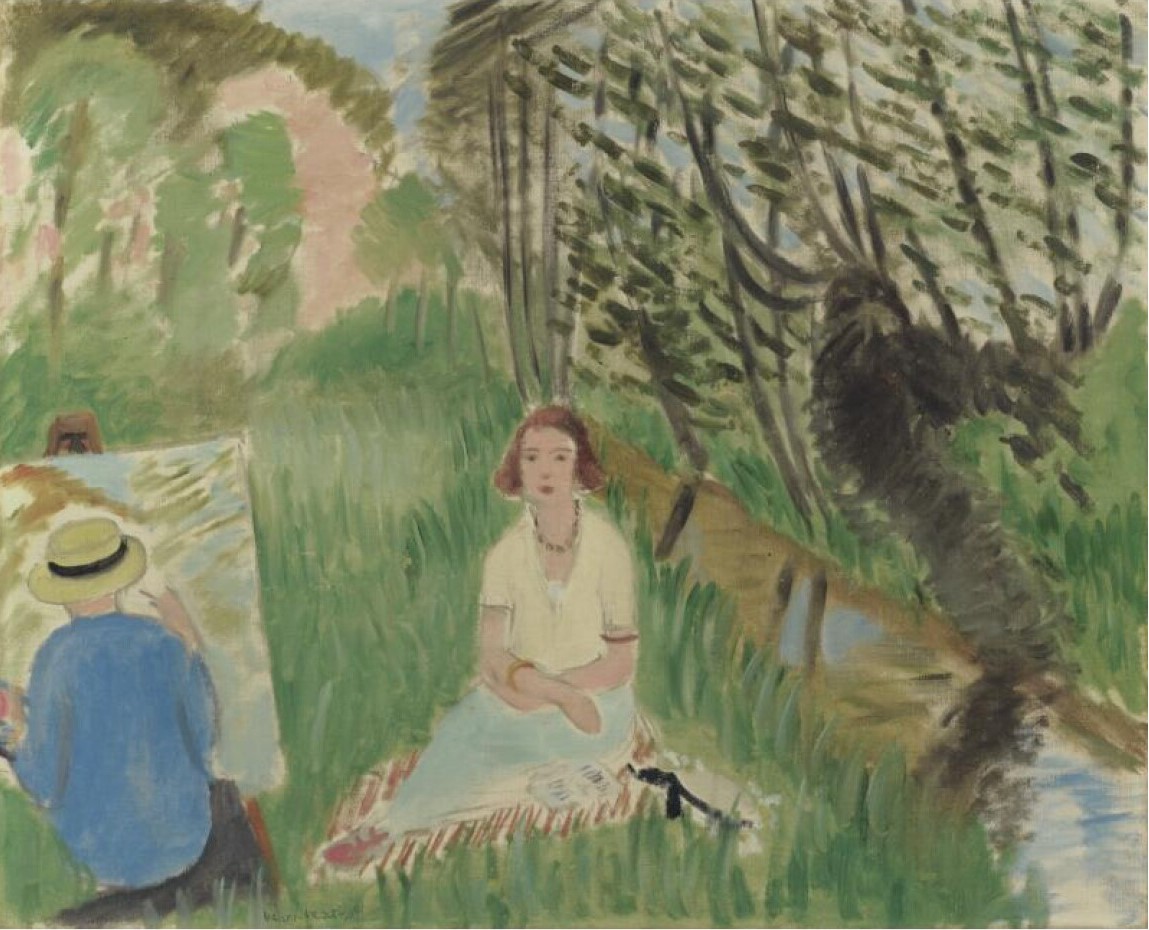

Henri Matisse painted “The Painter” in 1923, in the mature phase of his Nice period. By then he had spent several years refining a language of clarity—calm interiors, tuned color chords, and a soft, even light drawn from the Mediterranean climate. Yet the Nice program was never confined to rooms. With this canvas Matisse carries the ethic of measured harmony into the open air, staging an artist at an easel and a model seated on a blanket beside a narrow stream beneath a screen of trees. The picture reads as a manifesto in quiet form: the act of painting, the person being painted, and the enveloping landscape are bound into a single climate. Instead of the bravura plein-air narratives of the late nineteenth century, Matisse offers an image of work and looking that is intimate, lucid, and serenely contemporary.

Composition As A Triangle Of Gaze, Model, And Landscape

The design is engineered around a triangle whose vertices are the painter at left, the seated model near the center, and the dark, bending tree mass on the right bank of the stream. The painter’s back presents a rounded, compact shape in cobalt blue, crowned by a straw hat; his easel and canvas form a pale plane that tilts toward the model. The model, in a light dress, sits cross-legged on a patterned blanket; her upright torso becomes the composition’s chief vertical. The right side is a dense thicket: a dark trunk arches over water, and thin branches striped with leaves slant upward, turning the whole bank into a vibrating screen. The meadow’s long greens join painter and model along the base, while the stream’s diagonal ribbon of blue connects the model to the right bank and guides the eye into depth. The triangle does not dramatize conflict; it organizes attention. Each vertex returns you to the other two, so that the painter’s work, the model’s presence, and nature’s rhythms are felt as a single, circulating event.

The Painter Seen From Behind And The Ethics Of Attention

Matisse chooses to show the painter from behind, denying us his identity and dramatizing instead the act of looking. The back view is crucial: it invites the viewer to occupy the painter’s task without being distracted by personality. The bent head beneath the straw brim, the small movement of the hand at the canvas, and the square seat planted in the grass tell us that concentration has a bodily shape. The blue smock is not a theatrical costume; it is a chromatic mass that anchors the left side and performs a second job as color counterpoint to the surrounding greens. The easel’s pale field tilts slightly toward the model, creating a visual hinge that clarifies the painting’s subject—the relationship between seeing, making, and the figure in the meadow.

The Model’s Pose And The Poise Of Ease

The seated model is a signature Nice-period presence: composed, unforced, and alert. Her back is straight but relaxed, hands loosely joined in her lap, gaze directed outward just left of the viewer. She sits on a woven blanket whose short red and cream strokes mark the ground around her like a small aura. The pale dress and string of beads deliver a gentle interior rhythm to the center of the canvas, and the face—built from frank, economical planes—holds calm without stiffness. She does not perform for the painter; she shares the weather with him. That parity is the picture’s moral center: work and leisure, maker and sitter, human and landscape exist at one tempo.

A Landscape Constructed By Planes, Not Illusion

Depth is built with bands and tilts rather than linear perspective. The near meadow is a broad field of vertical and diagonal grass strokes, laid in saturated greens that lighten as they recede. The middle ground tilts up slightly toward the model and the stream, a typical Matisse strategy that clarifies space without forcing a deep tunnel. The far bank rises as an arabesque of trunks and leaf-studded branches; above it, sky opens in pale, breathing blues. The stream, a slim band of cool water, carries quick reflections and patches of sky, giving the composition a needed horizontal counter-movement. Everywhere, forms are summarized: a tree is a dark, bending mass; leaves are flicks; rocks are ochre planes; the painter’s canvas is a large, creamy note. The reduced vocabulary keeps the painting legible at distance and fresh at close range.

Color Chords And The Temperature Of Calm

The palette is a disciplined chord of greens and blues tempered by ochres and pinks. Grasses range from emerald to sap to light, minty notes, with warm ochre flashes where ground breaks through. The stream’s blue—cooler and cleaner than the blue of the painter’s smock—pulls the eye into depth and keeps the right bank from overheating. The model’s dress and skin sit in a soft family of creams and warm roses that echo the pink slope at upper left, binding figure to site. Black is sparingly used to articulate the darkest tree forms and the model’s hair; these calibrated darks provide punctuation without heavy outline. Because the colors belong to a single climate, the scene feels open and breathable. The painting does not push contrast; it undulates in tuned temperatures.

Drawing Inside The Paint

Matisse’s drawing lives in the pressure and direction of brushstrokes. The painter’s hat brim is a ring of quick arcs; the easel’s legs are two decisive diagonals; the model’s profile is a single, gently angled contour that meets the cheek with a warm-cool seam. Grasses are long, elastic pulls that sometimes separate into strands, sometimes fuse into fields. Branches on the right are written calligraphically, dark lines that thicken and taper as they cross the light of sky. The stream’s edges are wet blends, feathering greens into blues so that water and bank remain in conversation. Details are present—beads, blanket fringe, hatband—but always summarized, never fetishized. The authority is in the pace and certainty of the touch.

Light As A Continuous Outdoor Veil

The illumination is consistent with Matisse’s Nice ethic: a soft, enveloping light that clarifies without extremes. There is no theatrical spotlight; instead, a general brightness allows forms to be read by temperature. The model’s face warms slightly against the cool greens; the painter’s smock absorbs light into cobalt; the water records a quiet sky. Shadows are gentle and chromatic—the underside of the hat leans to olive, the right bank deepens to bluish black, the folds of the dress cool toward gray. The absence of harsh chiaroscuro keeps the painting’s mood humane. We sense time of day—late morning or early afternoon—without clockwork.

The Stream As Visual Conductor

The trickle of water is small but essential. It introduces cool horizontals into a field dominated by vertical grasses and slanted branches. It also provides a bright, reflective plane that catches sky and sets off the dark tree mass, making that right-hand form legible as volume rather than silhouette. The stream’s diagonal course intersects the model, travels behind the grasses, and exits near the lower right, carrying the eye with it. In a picture about making and seeing, this slit of water behaves like a gentle conductor, coordinating the passage of our gaze from painter to model to grove and back.

Rhythm, Repetition, And Visual Music

The painting’s pleasure is rhythmic. Vertical beats in the grasses repeat at different speeds and densities; diagonal slashes in the tree canopy march in parallel, a counter-rhythm to the verticals; rounded forms recur as hat brim, painter’s back, model’s head, and patches of sky. Color notes also return: the painter’s blue echoes in a cooler stream note; warm pinks move from distant slope to model’s cheeks and blanket pattern; deep greens are punctuated by brief black accents in tree and hair. The eye learns a loop—painter, canvas, model, stream, trees, sky—and each circuit yields a fresh syncopation, a cooler seam along the dress, a darker knot in the trunk, a lighter flick above the water.

The Meta-Painting: A Picture About Making A Picture

By placing the easel inside the scene, Matisse acknowledges the painting’s own process. Yet he avoids cliché. We cannot see what is on the painter’s canvas; we see only a pale, worked surface that rhymes with the meadow’s colors. This refusal of the “picture within a picture” trick keeps emphasis on attention rather than representation. The act of painting is presented as a way of joining the world’s rhythms—not dominating them. The model’s stillness, the painter’s concentration, and the landscape’s measured pulse describe one state of mind.

Material Presence And Tactile Hints

Every zone carries a distinct touch. The grasses are swept with full, loaded bristles that leave ridges; the stream is thin and smooth, so reflections feel liquid; the painter’s smock is opaque and velvety, absorbing the light; the hat is dry-brushed, catching the canvas grain so straw seems crisp; the blanket has small, clipped strokes that imitate weave. Such tactile variation makes the scene persuasive without literal detail. You can sense air moving through leaves, feel the damp edge of the bank, hear the scratch of bristles on the easel’s canvas.

Space Without Anxiety: Shallow Depth, Deep Calm

Matisse’s depth is limited on purpose. We are within a few meters of the figures; beyond them, a screen of trees concludes the space. This shallowness intensifies presence. The meadow’s color and the figures’ scale feel immediate, as if we’ve just stepped into the clearing. At the same time, the stream and the diagonal canopy prevent the space from flattening. The painting breathes with the comfort of a small garden rather than the drama of a vista. It is a world sized for attention.

Kinship With Other Nice-Period Works

“The Painter” converses with Matisse’s interiors from the early 1920s, but swaps carpet and curtain for grasses and branches. The model’s calm echoes the poise of his odalisques; the shallow, stacked planes recall his window pictures; the even light matches his studio scenes. What changes is the vocabulary: nature’s repeated strokes replace textile pattern, the stream replaces a window’s rectangle, and the painter’s back replaces an ornamental prop. The continuity shows how portable Matisse’s grammar is: whether inside or out, he builds worlds from tuned planes and humane rhythms.

The Viewer’s Path And The Experience Of Time

This is a painting that teaches you how to look by slowing you down. A quick glance delivers the subject: a painter and model in a green place. A longer look starts the loop. You feel the sweep of the grasses and the soft drag of the brush in the sky; you notice the model’s necklace as a string of dark beats; you follow the stream to the right and back again. On the third or fourth pass, micro-events emerge: the way a pink patch repeats in the far slope and in the model’s lips; how a single black stroke in the trunk anchors the leafy canopy; how a tiny wedge of blue on the painter’s canvas echoes the water. Time in the painting expands by attention rather than narrative. The longer you stay, the more the scene’s calm collects.

Why The Canvas Still Feels Modern

Its modernity lies in generosity and economy. With a few simple means—big fields, swift strokes, tuned color, minimal outline—Matisse composes an image of work and leisure that remains intelligible and fresh a century later. Designers can borrow its lesson in scale contrast: large grassy bands set against small accents in beads and blanket; painters can study how drawing can live within color; viewers can recognize a humane tempo in which presence, not drama, carries the day. The painting is not about virtuosity but about attention shared between people and place.

Conclusion: A Quiet Manifesto Of Making And Being

“The Painter” is a serene declaration of what art can be in Matisse’s Nice key. A figure works, a figure sits, trees whisper, a narrow stream threads the scene, and color keeps them company. There is no spectacle, only relations tuned to a single climate. Brushwork records perception in motion; light arrives as an even kindness; space opens just enough for air. By placing painter, model, and meadow in one balanced chord, Matisse proposes that making art is a way of belonging to the world—a practice of looking that turns work into calm.