Image source: wikiart.org

A First Look at “The Open Window” (1918)

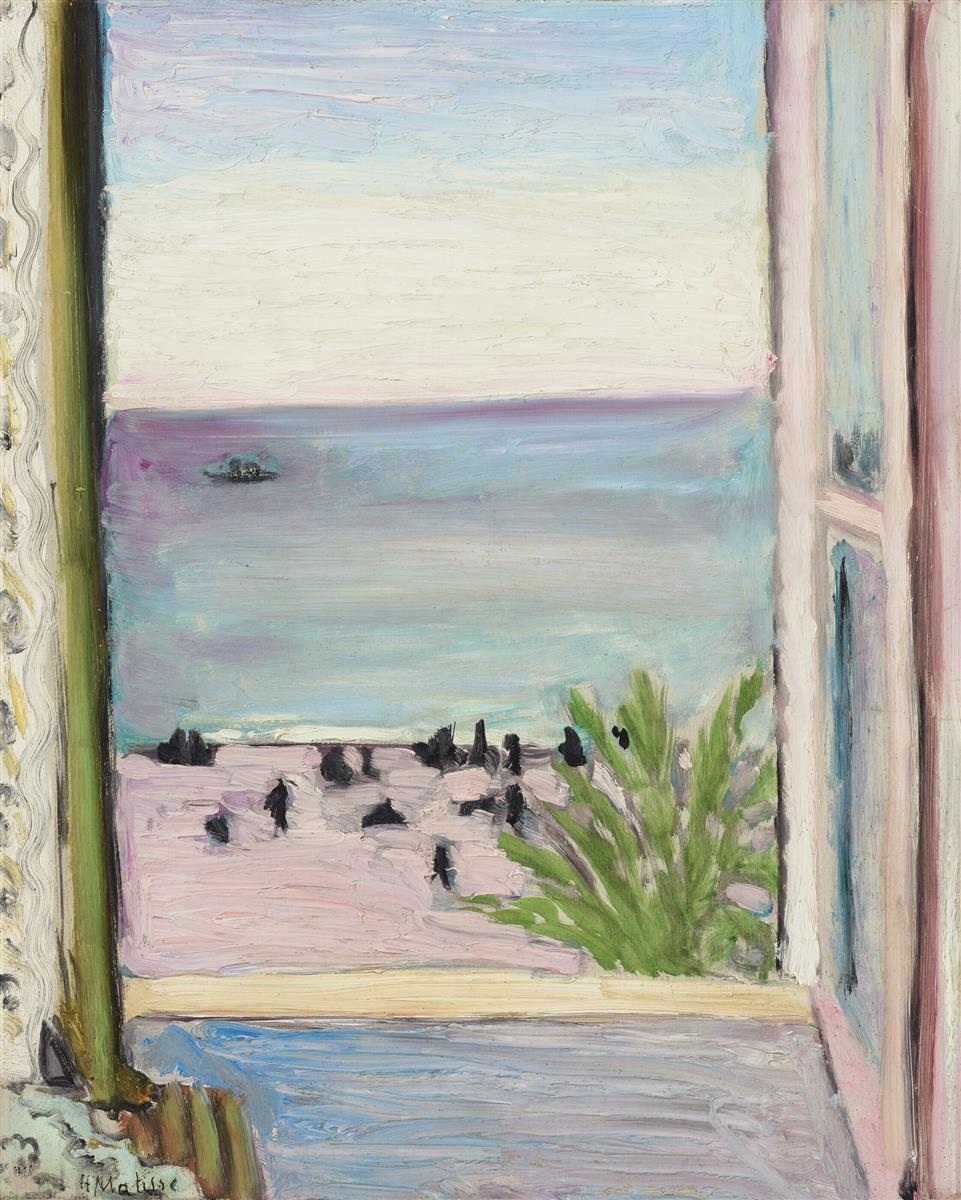

Henri Matisse’s “The Open Window” offers a quiet revelation: a small vertical canvas in which an airy Mediterranean vista is framed by the edges of a window and the faint suggestion of a curtain. The scene appears simple—pale sky, a band of lilac horizon, the flat shimmer of sea, a strip of light beach punctuated by dark notes that read as walkers or rocks, a sprig of green growth near the sill—yet the whole picture hums with carefully tuned relationships. Painted in 1918, at the dawn of Matisse’s Nice period, it distills his new southern light into a compact meditation on interior and exterior, object and atmosphere, material surface and visual breath.

A New Climate at the Start of the Nice Years

The date matters. After the blazing audacity of Fauvism and the severe experiments of the 1910s, Matisse settled in the Riviera seeking clarity, warmth, and the steadiness of daylight. “The Open Window” belongs to this pivot. He does not abandon the boldness of color or line that had defined his earlier reputation; he redeploys them toward serenity. The painting feels like a first inhalation of Mediterranean air through the studio’s window: a change of climate made visible. The palette cools into sea tints; the brushwork loosens without becoming slack; the subject is less a narrative view than an experience of light crossing a threshold.

Architecture of the Picture Plane

Compositionally, the image is almost architectural. Two uprights—on the left a green jamb with a sliver of patterned drapery, on the right a pinkish stile with a glinting pane—frame a central view that is stacked into horizontal bands. At the very bottom, a blue interior floor or sill plane creates a shallow stage; above it, a thin straw-colored strip reads as threshold; then comes the beach’s pale mauve; then the broad, near-monochrome plane of water; finally the soft ladder of sky shifting from cream to blue. These bands are not inert stripes. Each is slightly tilted or textured by directional strokes, so the eye glides rather than halts. The verticals of the window oppose these horizontals, establishing a stable cross that holds the view in place. With almost nothing—a frame, a few bands, a handful of accents—Matisse composes a complete world.

Color as Atmosphere and Structure

Color does the structural lifting. The painting’s chord is pitched in cool pastels: pearl, lilac, aqua, hyacinth blue, mint, a pinked white at the right-hand frame. Into this airy harmony Matisse inserts a few decisive notes—deep green along the left jamb, the grass-bright green of the plant near the sill, a constellated series of small blacks on the beach, and the tightest dark of all in the tiny boat on the water. The darks anchor the diaphanous palette; their scarcity gives them authority. The whites are not empty; they carry temperature. The sky’s upper band is a cool, faintly violet white; the beach’s lighter passages are warmer, almost rose. Because the palette is so restrained, tiny changes in temperature—one touch of warmer white near the horizon, a cooler blue dragged across the floor—become events.

Brushwork That Records Breathing

The surface is frank about its making. Matisse lays paint in short, slightly loaded strokes that change direction as they cross a plane. In the sky, these strokes float horizontally, their edges catching light and letting underlayers show through like air currents. Across the water, he drags paint more levelly, so the sea feels calmer, broader, thinner. The beach receives quick, broken touches that alternate between mauve and pale rose, establishing a felt texture without literal sand. The dark “figures” are not drawn figures at all; they are brief, calligraphic dabs, set atop the beach color and left to speak. Even the plant in the lower right is constructed with a few fan-like green strokes and a dot or two of black to mark depth. The handling is economical but never stingy; it invites the viewer to feel the time of painting as the time of looking.

Interior and Exterior in Dialogue

Matisse’s window pictures always stage a dialogue between the inside world of the painter and the outside world of light. Here, the interior is barely present: a sliver of floor, a lick of curtain, the wooden edges of the frame. Yet these small passages matter enormously. The blue floor holds the closest plane and cools the warmer band of the beach beyond. The left-hand edge, with its wavy patterned strip, reminds us that the view is framed by domestic life, not by a camera. The right-hand stile catches a high pale highlight that behaves like a column of light entering the room. This dialogue is the painting’s quiet theme: the world out there and the room in here exchange breath through the open window, and painting itself becomes the meeting ground.

A Calm Horizon and the Measure of Space

Depth is achieved with the simplest means. The horizon sits high, where sea becomes sky as the color values converge. The distance is not a dramatic recession but a gradual thinning of tone. A tiny dark fleck—a boat—fixes the scale of the water and stabilizes the horizon. Below, the beach’s mauve field sits flatter, its near edge marked by the pale threshold strip and by the green foliage that overlaps it. Because the window frame keeps space shallow, the outside world reads as a tapestry of near-abstract fields. You feel distance and flatness simultaneously. That dual reading is central to Matisse’s art: the scene is a view, but it is also paint arranged on a rectangle.

The Role of Black as Punctuation

The small black marks scattered across the beach are vital to the picture’s rhythm. They can be read as figures strolling, as stones, or even as the shadows of unseen beach furniture—but their primary function is musical. They punctuate a large, pale field; they create a beat. Notice how they cluster more densely near the plant and then thin out toward the sea; how their sizes vary, pushing some “closer,” others “farther”; how a single, isolated black fleck on the water carries the force of a full stop. In many of his works, Matisse uses black as a positive color; here it is also the score that keeps the airy palette from drifting out of key.

Light Without Illusionism

No literal sunbeam enters the scene, yet light is everywhere. Matisse avoids illustrative tricks—no glints on waves, no cast shadows defined by direction. Instead, light is the sum of relationships: paler sky against slightly darker sea, cooler blue against warmer sand, a high-value right-hand frame that seems to glow because the left jamb is deeper green. This is light as a painter understands it, constructed from values and temperatures rather than drawn as a thing in itself. The result is a visual air you can almost breathe.

A Conversation with an Earlier “Open Window”

Matisse had famously painted “Open Window, Collioure” in 1905, a declaration of Fauvist color in which flowerpots, shutters, and boats blaze in hot complementaries. The 1918 “The Open Window” converses with that earlier canvas while announcing a new state of mind. The motif is consistent—the framed view, the sea, the little boat—but where the Fauvist painting shouts, this one murmurs; where the earlier work exults in saturated oppositions, this one finds radiance in pastels and in the poetry of restraint. The difference is not loss of power but a change of key. By holding back, Matisse discovers another kind of intensity.

The Psychology of Stillness

Because the scene includes a beach and a boat, it tempts narrative. Yet the painting is not about events. It is about a moment of poised stillness when looking itself is the activity. The window is open; air moves; people or shadows dot the sand; but the sensation is one of settled calm. That calm is not vacant. It is the kind of mental quiet that follows prolonged attention—the way the mind feels after staring at waves long enough to forget time. The painting proposes that such attention is not escapism but a discipline, a way of ordering experience.

Material Clues and Intimacy of Scale

The panel’s small size matters. Seen up close, the paint ridges catch the light like grains of sand; the strokes that form the sea read like wrist-length gestures; the tiny boat is quite literally a single, direct touch. These intimate clues draw the viewer into the painter’s scale of action. You sense the proximity of the easel to the window, the quickness with which a sky color had to be laid before it cooled, the decision to stop before over-explaining any passage. That intimacy is part of the work’s tenderness: it feels like a view kept for oneself and then shared without fuss.

Edges and the Craft of Joining

Edges keep the harmony intact. Where sky meets sea at the horizon, the seam is violet and soft, a breath rather than a line. Where sea meets beach, the transition is firmer, because the beach’s texture requires a distinct edge to read as land. Where the plant overlaps the beach, green flicks create a lively, serrated boundary; where the right-hand frame meets the view, the painter slightly scumbles the edge so the “light” of the frame appears to spill into the landscape. Each edge is tailored to its local job, and together they give the painting its serene cohesion.

How the Painting Teaches Us to Look

There is a natural path through the image. The eye enters at the blue sill, rises to the pale threshold, slides over the mauve sand, pauses among the black punctuation marks, drifts across the sea, and comes to rest at the high, light sky. Then the verticals pull the eye back down along the right-hand frame; the patterned strip at left returns it to the start. This continuous circuit turns the act of looking into a gentle loop. The painting provides not only a view but a choreography for seeing.

The Window Motif as Metaphor for Painting

From Alberti onward, Western painting has been compared to a window onto the world. Matisse embraces and complicates that metaphor. His window is literal, but he insists on the presence of the frame, the sill, the curtain—a reminder that every view is mediated, selected, and bordered. By keeping these framing devices visible, he acknowledges that painting is an act of choosing how to see. The open window becomes a manifesto of openness itself: a porous border where the seen world and the made image meet.

Relation to Place and the Postwar Mood

Painted in 1918, the work registers a world seeking respite. It is not a political picture, yet its serenity is inseparable from the desire for restoration at war’s end. The beach is not crowded with holiday-makers; the boat is solitary; the colors are hushed. Matisse finds in the Nice climate a model for balance: a pale sky after tumult, a sea that refuses drama, air that circulates freely through the open room. The painting’s generosity lies in offering that balance without sermon or spectacle.

Why the Picture Feels Strikingly Contemporary

The canvas looks uncannily at home in the present. Its reduced palette and strong framing would not be out of place in contemporary photography or design; its visible brushwork satisfies a modern appetite for process; its emphasis on thresholds speaks to current interests in liminal spaces. Even the small black marks that stand for figures could be mistaken for minimalist notation. The painting’s modernity is not the shock of the new but the clarity of essentials.

A Close Reading of Key Passages

Consider the little plant at lower right. It is nothing more than a handful of green strokes, each slightly varied in hue; a few black dabs nestle among them to create depth. Yet as you attend to it, the plant sharpens into presence and even suggests a gentle breeze. Or look at the mauve beach: thin, horizontal strokes are interlaced with lighter, curved marks so the surface breathes rather than lies flat. Move to the upper sky: a soft, creamy band hovers just above the horizon, a delicate counter to the cooler blue above it. Each passage is modest yet precise; together they accumulate into a complete sensation.

Enduring Significance within Matisse’s Oeuvre

“The Open Window” is a keystone for understanding the Nice period. It shows how Matisse could make a picture expansive with almost nothing, how he could let air and light be the true subjects without abandoning the discipline of design. It also proves the durability of his central convictions: that painting is an arrangement of colors and lines meant to produce a state of balance; that simplification is a form of knowledge; that quiet can be as moving as brilliance. From this small window, a large chapter of his art opens.