Image source: wikiart.org

First Look: A Cliff, A Surge, And A Net Of Color

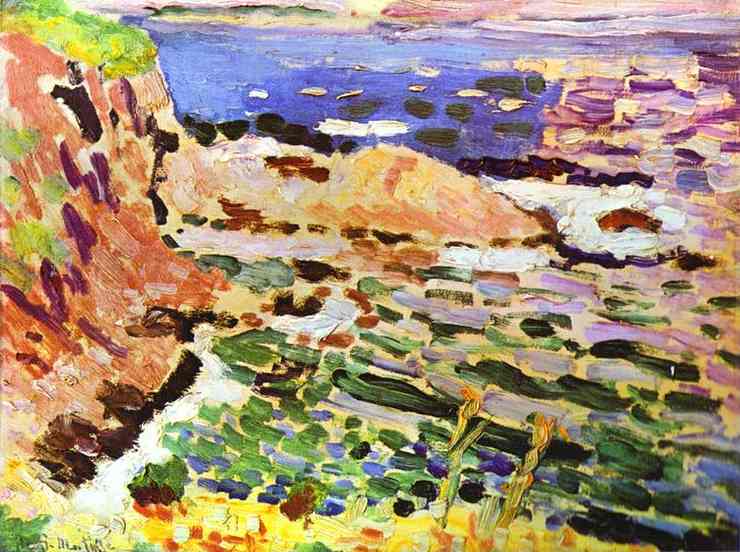

“The Moulade” plunges the viewer into a narrow inlet on the Mediterranean coast, all rock, foam, and wind-scumbled water. The cliff at left rushes downward in stacked planes of russet, mauve, and mossy green. Across the middle ground, low rocks and a pale outcrop break the surface. The sea is a dense weave of short, rectangular strokes—greens, ultramarines, lilacs, lemons—laid like tesserae. Foam flashes in thick whites, while the far band of water cools to cobalt and violet. Nothing here is blended into atmospheric softness. Matisse keeps each touch visible so the picture remains a living fabric of decisions. Even before one names the place, the sensation is crisp: a hot headland and a waterfield quivering under bright Mediterranean light.

The 1905 Breakthrough: From Scientific Dots To Living Strokes

Painted in the legendary Collioure summer of 1905, “The Moulade” belongs to the moment when Henri Matisse stepped beyond Neo-Impressionist theory and discovered the bolder, faster language that came to be called Fauvism. He retained a crucial lesson from Seurat—keep color notes separate so light can vibrate—yet abandoned the mechanically even dot. In its place he uses strokes that change size and direction according to what the motif demands. In the cliff they stack vertically like stone; in the sea they slide horizontally like chop; in the foreground they tumble diagonally with the undertow. The result is a surface that breathes while still holding together.

The Motif And Its Name

“Moulade” names one of the rocky coves on the Roussillon coast near Collioure. Matisse didn’t treat it as a postcard. He used the site as a laboratory where elements reduce to essentials: cliff, ledge, foam, open water. The title cues us to the real geography but the painting’s truth is experiential rather than topographic. What matters is how the sea feels when light breaks it into patterned, high-key fragments and how the cliff, pulsing with heat, holds its ground against the restless field of water.

Composition As A Tension Between Mass And Motion

The canvas organizes itself around two forces. The cliff is weight, rising off the left edge like a buttress and pushing diagonally into the picture. The water is motion, an all-over pattern that threatens to flatten the space into a decorative sheet. Matisse engineers a truce. He lets the cliff’s vertical thrust interrupt the sea’s horizontal flow, and he threads an S-curve of foam that guides the eye around the rock shelf to the central outcrop and back into the open blue. Repetition keeps the two realms in conversation: the cliff’s brushstrokes echo as darker, boat-shaped dashes across the water; the sea’s greens reappear as cool notes inside the shadowed rock.

Color Architecture: Warm Cliff, Cool Sea, A Bridge Of Violets

The picture is built from temperature zones rather than from conventional light-and-shadow modeling. The cliff lives in a warm spectrum: brick reds, ochres, orange-rose, and a scorched burgundy in fissures. The water lives in cools: viridian, teal, ultramarine, blue-violet. Where the two meet—along the foam line and around the central rock—Matisse inserts violets and lilacs that function as a hinge. Those violets are not local color; they are structure. They relate warm and cool without muddying either, and they carry some of the picture’s most persuasive depth.

Brushwork And The Logic Of Direction

Every stroke here does double duty: it states color and it states movement. Short, horizontal dabs in the sea describe wavelets and also keep the surface level; longer, slightly arced strokes in the foreground water suggest refraction and swell; tightly packed vertical notes in the cliff enforce mass. Matisse refuses to smooth these units into a single skin, because their edges are the very places where sensation happens. The eye can track them like steps, so looking becomes a walk through color.

The Sea As A Tiled Field Of Reflections

The water’s mosaic is not merely decorative. It models the physics of a bright day. Under strong sun, the sea does not read as one color; it resolves into a quilt of reflections—sky blue between troughs, green where the bottom shows through, pale lilac where thin foam films the surface, midnight dashes where the chop turns away from light. Matisse records this not with blended gradients but with neighboring notes. Because those notes remain distinct, they sparkle; because they repeat, they persuade.

Foam, Spray, And The White Of The Ground

The foam spends much of its time as bare canvas. In several passages Matisse lets the primed white do the heavy lifting, then pins it with a few creamy strokes. That reserve keeps the palette clean and replicates glare with a blunt honesty no mixture could match. The same tactic appears at the horizon, where pale, scrubbed paint lets the ground glint like haze. White here is not the last touch; it is the painting’s light source.

Space Without a Vanishing Point

Depth in “The Moulade” is felt rather than diagrammed. The horizon sits high, but there are no ruled orthogonals. Instead, space emerges from scale shifts and temperature. The foreground water carries bigger, more contrasted strokes; the middle ground compacts into tighter, cooler marks; the distance flattens to thin blues and mauves. Foam strings overlap rocks; rocks overlap bands of sea. Perspective happens as a sequence of relations: large to small, warm to cool, dense to open.

The Cliff As A Living Organism

Look long at the cliff and it ceases to be a single block. Green creeps through its ledges; mauve shadows cool their heated neighbors; a near-black seam splits one face from another. The stone feels porous and sun-soaked rather than monolithic. That vitality comes from Matisse’s refusal to glaze a uniform tone over the mass. He patches color like a mason, and each patch keeps a breath of edge, so geology becomes a living skin.

Rhythm And The Eye’s Path Through The Scene

The painting asks the viewer to move in a loop. The eye falls down the cliff’s incline, slips onto the foam ribbon, crosses to the pale outcrop, and then drifts into the cobalt distance. A band of dark dashes—like boat silhouettes or shadow pools—pulls the gaze back across the middle water. Two ochre seed heads in the foreground arise as comic, delicate exclamation marks; they pivot the eye upward to start the circuit again. Rhythm, not explicit detail, is what keeps the picture turning.

Divisionist Memory, Fauvist Daring

Seen alongside Matisse’s 1904 pointillist experiment “Luxe, Calme et Volupté,” this work keeps the idea that neighboring notes vibrate, but replaces optical system with intuition. The strokes here are not equal dots; they are flexible, responsive units. He also pushes saturation to a higher key—greens and purples closer to the tube, blues less polluted by gray. That higher key is not a decorative whim; it is the register at which a midday coastline actually seems to operate.

Material Facts: Impasto, Drag, And The Weave Of The Canvas

The paint has body where he wants weight. Whites of foam are laid on thick, so real light catches their ridges like sun on spume. The cobalt band at the horizon thins enough to show threads of the linen; that translucency reads as distance. In the cliff’s shadowed niches, strokes stack wet into wet, their edges softening without being smeared. The viewer learns to read material cues as landscape cues: thickness equals nearness and impact; thinness equals air.

Kinships Within The Collioure Series

“The Moulade” sits between the seascapes where color organizes itself into big planes and the grove paintings where small, repeated strokes weave a tissue of light. Here he chooses the grove’s vocabulary for the sea and the plane-based approach for the cliff. Compare it to the vertical “La Moulade” variant with its plunging viewpoint: the sister canvas concentrates on the coastline’s drop, while this one opens the water like a fan. Together they show Matisse testing how far color alone can build geology and tide.

Light And Hour

Everything points to strong early afternoon light. Long cast shadows are absent, yet contrast is crisp; the sea exhibits simultaneous violet and green; the cliff’s warms have little brown in them. This is not the soft gold of evening. It is the hard, clarifying light that reduces forms to planes and brings complementary colors into sudden harmony. By painting with pure notes rather than mixed grays, Matisse replicates that optical short-handing.

The Role Of Invention And The Truth Of Effect

Parts of the sea include dark ovals that could be boats, kelp rafts, or simply craft marks stabilizing the surface. Their ambiguity is not an error; it is a strategy. They keep the middle zone from dissolving and they pace the eye forward. Matisse remains faithful to the effect—how a windy surface speckles itself with voids—rather than to a checklist of objects. Accuracy lives in the relation among colors, not in the naming of each patch.

What The Painting Says About Fauvism

Fauvism is often reduced to wild color, but “The Moulade” shows how disciplined that wildness is. Colors are saturated yet interlocked by structure: foam lines, rock overlaps, repeating marks. Black is almost never used; darks arise from deep blues and greens, so the palette holds to a luminous logic. The method seems free because it is efficient, not careless. Every note has a job.

How To Look So The Picture Opens

Stand close and let your eyes follow single strokes as they meet their neighbors. Notice how a viridian dab turns into water when it sits between lilac and lemon. Step back and watch the cliff’s warm mass stop the sea’s spread. Return to the foam and see how much of it is simply the canvas itself, left to shine. Move to the horizon and recognize that the thinned cobalt and the mauve streaks are doing the labor of miles of air. Repeat the circuit until the surface stops looking “broken up” and starts reading like weather.

Why It Still Feels New

More than a century on, the painting remains vivid because it relocates truth from descriptive detail to optical behavior. It acknowledges that in hard sun we read the world as mosaics before we knit them into solids. It proves that leaving strokes open and ground exposed can render brightness more convincingly than smooth blends. It insists that color is not a garnish but a structural tool capable of holding cliff, sea, and air in a single, convincing chord.

Conclusion: A Cove Made From Temperature And Tempo

“The Moulade” condenses Matisse’s 1905 invention into one lucid seascape. The cliff is a warm engine of mass; the water is a cool engine of motion; violets act as a hinge between. Brushstrokes are the units from which reality is built, not veils hiding it. Light comes as much from what he omits—reserves of canvas, unblended boundaries—as from what he lays on. This small inlet therefore holds a larger lesson: when color is freed to do structural work, landscape becomes both more decorative and more exact, a place one can feel in the body as much as see with the eyes.