Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

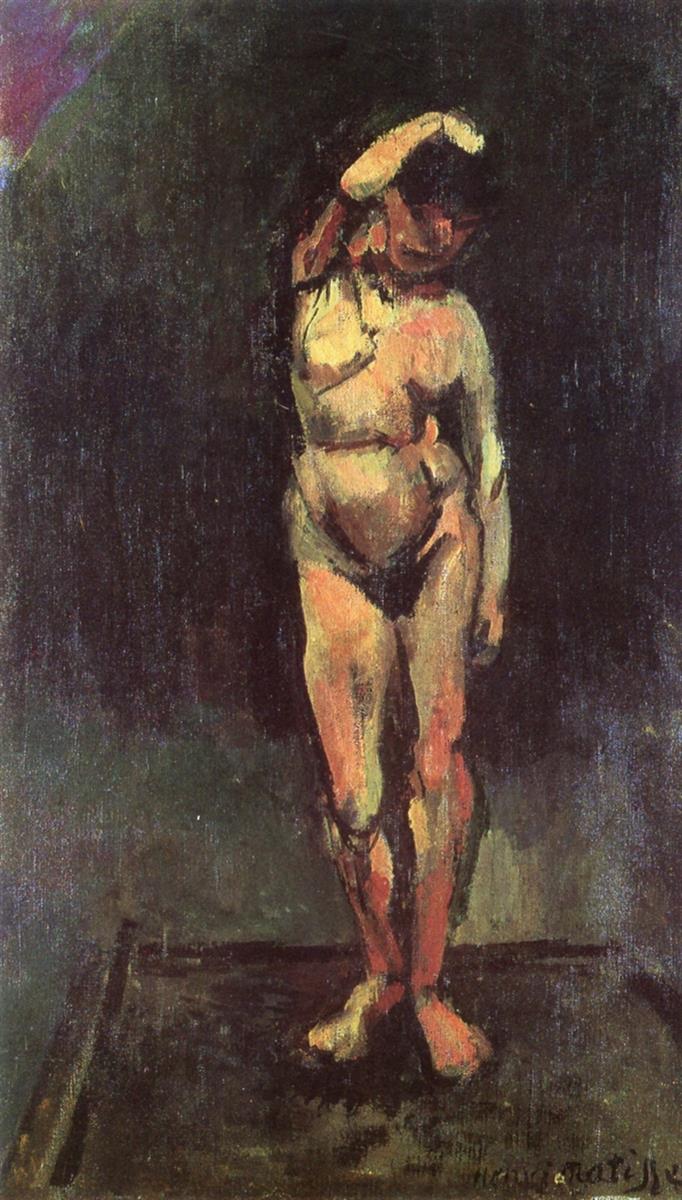

At the turn of the century Matisse was learning to shed the habits of academic finish without abandoning rigor. “The Model” is a pivotal experiment in that process. Rather than presenting a polished, anatomically diagrammed nude, he sets a living body within a compressed stage of darkness and builds form with abrupt, square-edged planes of color. The pose is simple and archaic—a vertical figure with raised arm—but the painting’s urgency lies in the choices of value, temperature, and touch. Every surface is considered, yet nothing feels over-explained. This is a studio picture about looking hard and deciding what truly matters.

Subject, Pose, and Setting

The figure stands on a low platform, her weight settled into the right leg, the left slightly forward, toes pointed inward. The right arm rises to the crown of the head, tilting the skull and opening the torso’s diagonal. With the left arm relaxed along the body, the pose combines closure and exposure, an art-school classic that shows masses and joints without flourish. The studio is barely stated. A dark wall meets a darker floor; a thin, warm strip at the lower left hints at a board or frame; everything else is swallowed by atmosphere. The spareness places the burden on the model and the painter’s decisions about light.

Composition and Armature

The composition is an unambiguous vertical built on a triangle. The apex is the lifted hand and tilted head; the base is the wide stance of the feet at the bottom edge. The torso and raised forearm create a long diagonal that keeps the figure from stiffening into a column. A shallow platform functions as a stabilizing horizontal, while a faint left-hand border and darker right edge make a silent proscenium. The body’s central axis is slightly off the canvas center, giving the left side more breathing room and letting the right-side darkness press inward. The result is a figure that stands, breathes, and occupies real weight without the prop of elaborate setting.

Color Architecture

Matisse’s palette is limited but carefully tuned. The ground is a smoldering mixture of green-black and brown-violet, modulated just enough to prevent dead flatness. The flesh is built from a handful of notes—yellow ochre, terra rosa, pale grey, black-green shadows—laid in with quick planes. These notes do not blend; they abut. Where the thigh turns from light to shadow, a rectangle of warm ochre hits a cooler olive. Where the chest rolls under the collarbone, a pale, chalky pink butts into a deeper red-brown. Because the colors are chosen for temperature as much as value, the body reads as three-dimensional even when edges are blunt.

Light as Temperature, Not Spotlight

Illumination in “The Model” is not theatrical; it is a field condition. There may be a single studio lamp out of frame, but the effect is achieved by temperature contrasts rather than beams. Warm planes advance; cool ones withdraw. The raised hand and the shoulder nearest us flare into pale, warm notes; the far arm sinks into olive-gray; the belly and upper thighs take on a redder heat. This distribution conveys both the turning of form and the feel of skin under light—soft but definite, with no syrupy gloss.

Drawing by Abutment

Matisse resists descriptive contour. Take the right hip: there is no line. The hip exists where a warm block meets a cooler shadow; the edge is simply the seam between temperatures. The breast is not encircled; its curve appears where a lighter plane pivots against a darker one. Even the toes are hammered out by small value steps instead of outlines. This “drawing by abutment” is crucial to Matisse’s later language: forms are negotiated rather than fenced in, and the picture breathes as one atmosphere.

Surface and Touch

The paint film is varied but never fussy. Background layers are scumbled—thin pigment dragged over darker underlayers—so the studio wall feels grainy and deep. Flesh passages carry more body; strokes are short, chiseling, and directional, echoing bone and muscle. Occasionally a loaded highlight—on the lifted wrist, the top of the thigh, the bridge of the foot—catches light literally as a thicker fleck. These touches keep the skin tactile without pedantry. Where the painter chooses to leave roughness, it reads as honest looking rather than neglect.

Space, Depth, and the Platform

The platform grounds the body. Its trapezoid shape, slightly tipped, sets the figure in shallow space and emphasizes foot placement. A dark band at the platform’s far edge doubles as a compositional bar, holding the legs in. The wall behind the figure is sufficiently neutral in value that the silhouette remains legible without hard edges. One can measure depth simply by the way the feet cast dense, horizontal shadows and by how green-black softens near the floor. Nothing in the picture is anecdotal; everything serves the stability of the figure.

Anatomy Reduced to Planes

Matisse does not ignore anatomy; he distills it. Knees are wedges, the iliac crest a broken angle, the ribcage a set of stacked planes under a thin skin of light. The raised arm is a column built from three volumes—upper arm, forearm, hand—each turning by temperature, not by contour shading. There is candor in the way he describes the belly, pubic triangle, and thighs: no stylization, no idealization, just practical planes locating weight and balance. This frankness separates the picture from Salon nudes and aligns it with the more constructive, structural approach learned from Cézanne.

Psychological Temperature

Despite its studio neutrality, “The Model” carries a clear mood. The dark ground presses close, and the body gleams as if discovered rather than displayed. The lifted arm and tilted head imply a moment of adjustment—scratching, arranging hair, reacting to the pose. The face is intentionally withheld: features dissolve into dark, with the cheekbone and a touch of mouth barely indicated. That occlusion shifts emphasis from portrait likeness to bodily presence and to the painter’s project: modeling a human mass with color. The emotion is not eroticism but concentration.

The Role of Shadow

Shadow in this painting is color, not black. The armpit, under-breast, and groin are tinted with greenish umbers and maroons that remain alive within the dark. The most persuasive form-turnings happen where warm light plays into cool shadow with minimal blending—a practice Matisse will repeatedly exploit. Notice the left calf: a warm, streaky highlight falls over a cool underplane, describing roundness with two notes. At the feet, a ring of heavier darkness pins the figure to the platform and prevents float.

Edges and Transitions

Matisse varies edge quality to guide attention. Harder, more assertive edges occur at the shoulder’s lit contour and the outer calf; softer dissolves occur at the far arm and hip where the body merges into the ground. The head’s top edge is surprisingly sharp due to the bright note on the hand and forearm, which cuts cleanly into the dark; the face’s lower edge is lost, absorbed by shadow. This orchestration makes the eye linger on the crucial pivots—the lifted arm, the hip, the knee—and glide through less important connections.

Comparisons and Influences

The painting’s constructive planes and refusal of sugary finish recall Cézanne’s bathers and late nudes. From the Nabis, Matisse retains the courage to simplify the ground into a single color field. There is also a hint of Courbet’s material frankness in the way flesh is paint first, anatomy second. Yet the temperature-led drawing and the willingness to let dark absorb detail point ahead to Matisse’s own interiors and figure paintings of 1905–1908, where chroma becomes even more autonomous.

A Transitional Aesthetic

Why does “The Model” matter in Matisse’s evolution? Because it shows the painter rehearsing three principles he will soon radicalize. First, color carries structure; he can build a leg with two or three planes of different temperature. Second, the background is not scenery but an active field that declares the painting’s flatness while holding a believable space. Third, economy and emphasis trump enumeration; he describes the necessary and omits the rest. These lessons will ground the freedom of the Fauves, preventing color from becoming mere decoration.

The Nude and Modernity

Classical nudes often idealize; naturalist ones often narrate. Matisse chooses neither. His model is a person present to light and gravity, not a myth or anecdote. The body’s asymmetries, the weight in the abdomen, the unflattering press of shadow are recorded without apology. At the same time, the figure becomes a locus for abstract decisions—vertical against horizontal, warm against cool, thick against thin. In this double allegiance to fact and abstraction lies the modern nude’s program.

Material Evidence

Look closely at the weave showing through the dark field; Matisse allows the ground to participate. Around the feet, scraped passages reveal earlier paint and adjustments. The hand raised to the head carries the most loaded highlights, suggesting that he may have returned there last to secure the composition’s apex. The signature in the lower right sits in the same dark recipe as the floor, not an afterthought but integrated into the value range—one more sign that the whole surface has been considered as a unified skin.

How to Look Slowly

Begin at the lifted wrist, where a small, bright plane catches light and declares the painting’s highest value. Follow the forearm down to the head and feel how the face is withheld, becoming a dusky wedge under the brim of hair. Drop to the clavicle where small, cool planes intersect warmer ones to map the ribcage. Drift across the belly where ochre squares slide into deeper maroons around the navel. Step to the right hip and sense how one clean temperature seam creates the curve. Slide down the thigh to the knee, where a single oblique highlight is enough to convince you of bone beneath. Finally, land on the feet, dense and redder, locked to the platform by short, dark bands. Then step back and let the figure reassemble from planes into person.

The Painting’s Rhythm

The picture’s tempo is slow and vertical. The long column of the body rises from the base, checked by the horizontal of the platform and punctuated by the bend at the elbow and knee. Within that slow beat, small syncopations keep the eye alert—the flicker of a cool shadow at the belly, the hot notch at the hip, the icy highlight at the wrist. Nothing is frenetic, yet nothing is static; the body seems to sway quietly inside the rectangle.

Emotional Honesty

There is a sober respect in “The Model.” The artist looks without moralizing or sweetening; the model stands without coquettishness. The darkness is not menace but privacy, a studio’s protective envelope. The raised arm suggests passing time—the strain of holding a pose, the negotiation between body and task. Because the image denies anecdote, it invites empathy: we feel the weight in the legs, the heat under the lights, the pause between motions.

Anticipations and Afterlives

Within five years Matisse will flood a figure with arbitrary color—greens in faces, oranges in shadows—yet the shapes will hold because of the constructive habits practiced here. In later Nice interiors, the nude often glows in pale daylight; even then, edges are negotiated by temperature and planes, not by contour—a continuity traceable to this study. “The Model,” then, is both a record of struggle and a manual of methods he never abandons.

Conclusion

“The Model” stands at the threshold of Matisse’s mature colorism. Against a dark, featureless field, a human body is carved from neighboring planes of warm and cool. Contours are discovered, not drawn; light is a system of temperatures, not theatrical beams; the studio becomes an arena for decisions rather than a stage for story. The painting’s power lies in its candor—of anatomy, of process, of intention. In a single vertical figure, Matisse shows how modern painting could honor the body and free color at once, setting the terms for the decade to come.