Image source: wikiart.org

Historical Context And The Intimate Turn In Matisse’s Art

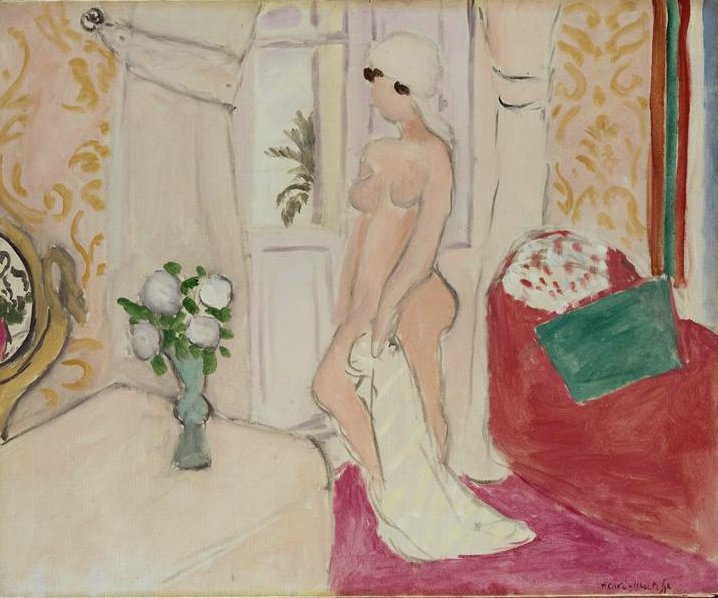

Henri Matisse’s “The Maiden and the Vase of Flowers” was painted in 1921, at a moment when the artist’s attention swung decisively toward interiors, ornament, and the poised presence of the human figure. The trauma of the preceding decade had nudged much of European art toward austerity, but Matisse moved in the opposite direction: he cultivated rooms where color, fabric, and light created a sanctuary for looking. Rather than chasing the extroverted shock of early Fauvism, he refined a language of calm clarity. This canvas belongs to that mature period, when Matisse simplified forms to their most telling contours and organized whole scenes around a few resonant relationships—here, a standing nude, a vase of pale flowers, and the soft architecture of a room washed in pinks, creams, and warm reds. The title already hints at a small drama: maiden and vase, body and still life, flesh and bloom. The painting holds them together inside a gently theatrical space that feels at once staged and lived-in.

Composition As A Theater Of Relationships

The composition is shaped like a shallow stage. On the right, a divan or cushioned seat swells in deep rose and carmine, with a green cushion propped at angle and a white patterned pillow tucked behind it. On the left, a tabletop tilts toward us, encouraging the eye to glide inward; a round mirror’s gilt rim peeks from the far left margin, while a slim ceramic vase stands near the table’s edge holding open, white blossoms. The central vertical is the door or window, a pale lavender plane broken by a slim palm outside. Before it stands the maiden, toweled hair implied by a creamy cap, a draped cloth gathered loosely at her hand and falling along her leg to pool on the pink carpet. The figure’s posture is quiet but charged, a slight contrapposto that brings a gentle S-curve to the silhouette. Everything is organized to place her in dialogue with the vase. The table and the divan form two lateral brackets; the patterned wallpaper vibrates like a backdrop. The entire room becomes a proscenium where body and blossoms share visual weight.

The Figure As Contour And Volume

Matisse’s nude is drawn with astonishing economy. The head is turned in profile, the features reduced to a soft brow, a single dark almond of an eye, and the barest indication of nose and mouth. The shoulder rounds forward, the breast is registered with a swift convex line, and the torso thickens toward the hip with a fullness that feels both sculptural and tender. There is no pedantic modeling, no fuss over musculature, no fetish for surface texture. Instead, contour carries character. The line swells and thins like a breath; it is never fencing off the body from space but rather coaxing it into being. A narrow ribbon of gray shadow at the figure’s back and inner arm is enough to set the body forward, while the white drapery, broken by a few soft creases, anchors the form to the floor. The result is an image of presence—neither idealized goddess nor private portrait but a person distilled to essentials.

Color Palette And The Temperature Of Calm

The palette is a lucid chord of pinks, creams, warm yellows, and sage greens, tuned in a way that allows the room to feel both airy and grounded. The pink carpet, rich yet cool, sets a gentle stage for the flesh tones. The wall’s patterned yellow or gold unfurls in stylized vines, their warmth balancing the coolness of the lavender door panels. The red divan deepens the register, providing a mass of color against which the figure reads with clarity. Greens are inserted with care: the leaves in the vase, the square cushion on the divan, the faint palm outside the door. They are counterpoints that keep the pinks from melting into sweetness. Matisse’s genius here lies not in extravagant saturation but in temperance. Each area of color has room to breathe, and the few accents of higher chroma—deep carmine on the couch, bright green of the cushion—steady the composition without shouting.

Brushwork And The Sensation Of Air

The paint handling is brisk but unhurried, the brush moving in even, confident sweeps. In the wallpaper, strokes follow the tendrils of pattern, lightly overlapping the pale ground so that the motif feels breathed onto the surface rather than printed. The tablecloth is creamy, with the subtlest shifts that let the underlayer of canvas peep through and lend a natural lightness to the textile. The door or window panels are thinly painted, almost scumbled, so they glow softly as if lit from behind. The maiden’s body is formed from slightly thicker paint that creates a velvety matte; this gives the skin visual substance while keeping it integrated with the surrounding air. The bouquet’s blossoms are small circular touches, a few grays and whites placed just so to suggest roundness, while the leaves are swift teardrops of green. These touches never chase botanical verisimilitude; they offer the sensation of flowers in a room where air is moving gently.

Ornament As Structure Rather Than Decoration

Matisse’s interiors are famous for their patterns, but ornament is never merely decorative in his hands. Here, the wallpaper’s curling foliage frames the maiden’s pale silhouette, offering a soft, vibrating edge against which the body is read. The mirror’s gilt rim at the left provides a counter-curve that echoes the curve of the maiden’s back and hip, subtly binding the far and near zones of the room. The patterned pillow on the divan keeps the right-hand mass from becoming a solid color block; its peppered white reinforces the floral whites on the table, establishing a scattered constellation of pale accents that carry the eye around the room. Ornament thus becomes a system of scaffolds, freeing the artist to simplify the figure without losing compositional complexity.

The Dialogue Between Body And Vase

The painting’s title demands attention to the conversation between the maiden and the vase of flowers. Their relationship is not allegorical in any heavy-handed way; it unfolds through echoes and contrasts. The blossoms, round and pale, rhyme with the rounded forms of shoulder and breast. The vase’s narrow neck mirrors the figure’s own neck, while the splay of leaves repeats the splayed fingers of the maiden’s hand where it grips the cloth. Yet the vase is cool ceramic, the body warm and sentient. One stands on a table, the other on a carpet; one is cut and arranged, the other poised and alive. The title sets up a moment of comparison that encourages viewers to weigh vitality and stillness, arrangement and spontaneity. The painting’s poise suggests that both are necessary in the making of beauty: the tender order of a bouquet and the free, breathing presence of a person.

Light, Thresholds, And The Window Motif

Behind the figure a pale door or window opens onto a sliver of exterior where a palm frond appears. This is a classic Matisse device: a threshold that admits outside air into an interior, reminding us that rooms, like paintings, are membranes rather than boxes. The light that enters is gentle, neither hot Mediterranean blaze nor cold northern glare. It is the sort that dissolves edges, softening the boundary between body and background. The faint palm introduces a distant rhythm of leaves, answering the wallpaper’s botanical curves and the bouquet’s foliage. This small glimpse outward also folds time into the scene; the maiden is just at the moment of moving, perhaps having drawn the curtain, perhaps about to step toward the light. The painting captures an interval rather than a pose, which is part of why it feels so inhabitable.

Drawing As The Intelligence Of Omission

No single line here is casual. The contour around the face is withheld at the front of the profile, letting the eye complete the edge against the light. The arm is a single, slightly elastic stroke that thickens at the elbow and thins toward the wrist, an eloquent sign of anatomy without description. The cloth’s lower edge is drawn with an easy, swaying line that suggests weight and fabric all at once. The tabletop corners are deliberately softened, so the plane tilts toward us without slicing the space. One could say that Matisse draws by choosing what not to say. The omissions are intelligent: where information would clutter, he trusts the viewer’s perception to supply it. This trust is central to the pleasure the painting offers.

Space Organized By Planes, Not By Depth Tricks

Traditional perspective is barely invoked. Instead, Matisse builds space from overlapping planes and temperature shifts. The table hovers in the foreground as a gentle trapezoid. The divan swells along the right edge, its upper curve slipping behind the figure’s thigh. The door panels are stacked rectangles that recede not by measurable orthogonals but by cooling in color and thinning of paint. The rug’s deep pink anchors the lower zone like a stage apron. These planes press against one another calmly, creating a shallow but breathable space in which the figure can stand comfortably. The result is not the illusion of a room measured in yards but a room constructed in relationships—near made by warmth, far made by coolness, and forward made by contrast.

The Nude As A Modern, Interior Subject

Matisse’s nude is not set in a mythic landscape or a bourgeois boudoir’s narrative. She belongs to a modern interior that has the clarity of a studio and the coziness of a home. By refusing anecdotal props and extensive detail, the painting acknowledges the tradition of the nude while insisting on the present tense. The towel on the head and the drape in the hand imply bathing, but the emphasis is on the body’s relation to shape and color rather than on bath-time story. This modernity is ethical as much as aesthetic; the figure is not exposed for a prurient gaze but offered to the eye as a form among forms, dignified by its integration with the whole.

The Role Of The Mirror And The Quiet Self

At the far left the mirror’s oval and gilt lip introduce the idea of self-reflection without showing a reflection. Its face is turned away, and we glimpse only a sliver of what it might contain. This restraint is telling. While mirrors in art history often function as sites of vanity or self-awareness, here the mirror is a formal counter-shape and a promise that the subject could, if she wished, see herself. The painting chooses not to show that moment. Instead, it shows the interval before or after looking, when a person is simply present. The mirror thus becomes a symbol of withheld narrative and of privacy respected—again consistent with the painting’s overall ethic of gentleness.

Materiality And The Domestic Modern

Everything in the room is palpably material but not fetishized. The ceramic vase has a chalky surface, the tablecloth a soft nap, the divan a dense cushion of pigment, the towel a light fall. Matisse lets paint describe these materials through touch and temperature rather than minuscule detail. That choice aligns with the domestic modernity of the scene: it is a room to live in and breathe in, not a showroom full of trinkets. The painting becomes a study in how a few beautiful things—a comfortable seat, fresh flowers, patterned walls, clean light—can create a dignified environment for a body to inhabit.

Rhythm, Repetition, And Visual Music

The painting’s visual music flows from repeated shapes and intervals. Circular forms echo across the canvas: the blossoms, the mirror rim, the roundness of shoulder and hip, the clustered pillow forms. Vertical rhythms appear in the door panels and the long fall of the drapery. Oblique diagonals cut gently across the scene in the tilt of the table and the cushion, preventing any hint of stiffness. These repeated patterns are never rigid; they are syncopated just enough to keep the eye moving. Matisse’s musicality lies in spacing and pause, in how he places a quiet area next to an active one so that the whole feels composed rather than crowded.

Sensation Over Description And The Poise Of Stillness

What one remembers after looking is not a catalog of items but a sensation: the coolness of lavender light, the warmth of the carpet underfoot, the quiet perfume of flowers, the softness of patterned walls, the presence of a person between movement and rest. Matisse achieves this by allowing stillness to carry energy. The maiden does not gesture dramatically; she simply stands, and the drama is transferred to the relationships around her. The painting’s poise invites a slower kind of viewing in which the eye lingers on modest transitions—the way a shadow edges an arm, the way a green note balances across the room, the way a pattern dissolves near a corner. That slowness is not lack of content but its fulfillment.

Parallels And Departures Within Matisse’s Oeuvre

This canvas relates closely to Matisse’s Nice-period interiors where odalisques recline among fabrics and screens. Yet it departs from the more luxuriant versions by trimming the orchestra. Here the number of players is small: one figure, one vase, one divan, one table, one door. The restraint yields clarity. The pinks and creams recall the airy harmonies of his coastal scenes from the same years, while the figure’s serene contour anticipates the distilled power of his later drawings and cut-outs. The work acts like a hinge in his development, preserving the sensuous pleasures of color and pattern while moving steadily toward the simplifications that would define his late style.

The Viewer’s Experience And The Ethics Of Looking

The viewer’s path begins at the vase on the table—a small invitation—and then moves to the figure, whose profile directs us toward the light. From there the eye slides to the divan, rests on the cushion’s green, and returns by way of the carpet’s pink to the table and the flowers again. The loop is gentle and repeats easily. Throughout, the painting refuses to turn the figure into a spectacle. The absence of strong outline around the face, the modesty of the stance, and the interlacing of body with patterned space encourage an appreciative, contemplative gaze. The ethics are clear: beauty can be looked at with respect when the painting’s structure honors the subject’s presence rather than claiming it.

Lasting Relevance And The Promise Of Calm

In a restless visual culture, the canvas still feels newly relevant because it models a form of attention that is both focused and kind. It shows how to build a complete world from a few tuned elements and how to let color do emotional work without excess. The room is not an escape from reality but a refined corner of it, where looking becomes a form of care. The combination of a living human being, a simple bouquet, and an open threshold suggests a philosophy of sufficiency: a little light, a few flowers, a comfortable seat, and the courage to stand at ease. That sufficiency is the quiet promise at the heart of the painting.

Conclusion: A Room Where Presence Blooms

“The Maiden and the Vase of Flowers” stands as a delicate manifesto for Matisse’s mature vision. It balances body and object, pattern and plainness, interior calm and the hint of outdoors. The figure’s contour, the flowers’ cool bloom, the soft architecture of color, and the flexible brushwork collaborate to create a room where presence can bloom without spectacle. Few painters have known how to transform so little description into so much life. In this canvas, everything essential has been kept, everything inessential quietly set aside. The result is an image that continues to breathe—bright, poised, and tender—as long as a viewer stands before it.