Image source: wikiart.org

First Impressions and the Instant Spark of Personality

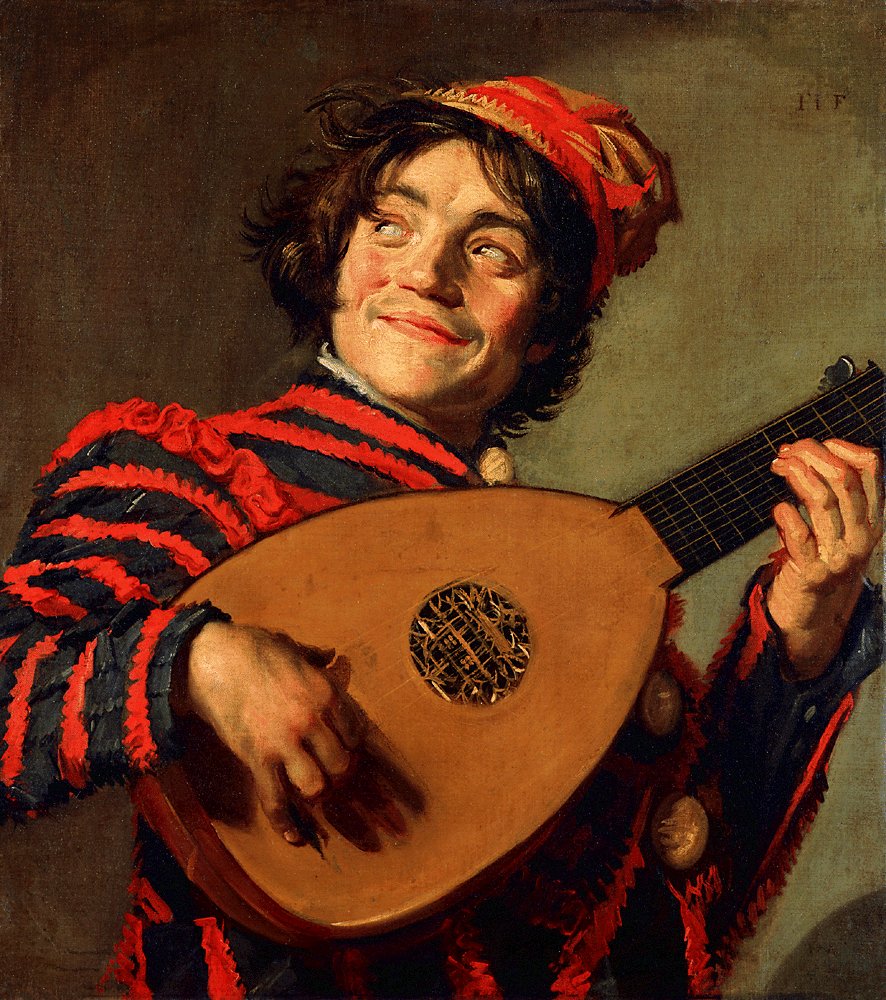

Frans Hals’s The Lute Player (1624) hits with the force of a grin you can almost hear. A young musician, dressed in bold red and black stripes with a jaunty cap, turns his head slightly and smiles as if reacting to a joke just out of frame. He holds a lute close to his chest, one hand poised on the strings, the other gripping the neck with casual confidence. The portrait feels mid performance, not staged after the fact. Hals captures the moment when music, humor, and social attention collide, turning a painted figure into a living presence.

The painting’s power lies in its immediacy. It does not ask you to admire from a distance. It pulls you into a shared space of entertainment. The sitter’s expression suggests charm and a bit of mischief, and the angle of his gaze implies an audience. We, as viewers, become part of that audience. The portrait becomes a performance that continues every time someone looks at it.

Hals and the Appeal of the “Lively Type”

Hals is often celebrated for portraits that feel alive, and The Lute Player sits at the heart of that reputation. Unlike formal civic portraits or sober depictions of wealthy patrons, this work belongs to a world of genre like character studies, images of everyday types, entertainers, and figures who embody mood more than social rank. Yet Hals never reduces the sitter to a cartoon. Even when painting performers, he gives them individuality and psychological presence.

In Dutch culture, such figures could serve multiple functions. They could be appreciated as amusing scenes of everyday life, as demonstrations of artistic skill, and as subtle moral prompts. Music and laughter were often associated with pleasure, spontaneity, and the fleeting nature of enjoyment. A musician might represent vitality and sensuality, but also the passing moment. Hals thrives in this territory because his brushwork and his eye for expression naturally suit subjects defined by movement and mood.

The portrait therefore works on two levels. It is entertaining in the most direct sense, a cheerful image of a musician. But it is also an exploration of what it means to capture a moment that is, by nature, temporary. Music vanishes as soon as it is played. Hals turns that vanishing art into a visible presence.

Composition and the Feeling of a Snapshot

The composition is tight and cropped close. Hals places the figure near the picture plane, bringing the lute forward so it becomes a dominant shape in the foreground. This creates immediacy. We do not feel like we are looking across a room. We feel as if we are right next to the performer, close enough to notice the warmth in his cheeks and the slight twist in his smile.

The diagonal of the lute neck adds energy. It cuts across the upper right portion of the painting and counters the rounded body of the instrument. The figure’s shoulders and arms form a natural frame around the lute, making the musician’s act central to the portrait. The instrument is not a symbolic accessory placed politely at the edge. It is physically integrated into the sitter’s posture, shaping how he occupies space.

Hals also uses the head turn to suggest motion. The sitter’s face is angled, as if he has just glanced toward someone. That glance gives the painting its narrative spark. Something is happening outside the frame, and the musician’s expression is a response. The viewer is invited to imagine the unseen social situation: a tavern, a gathering, a street performance, or a domestic party where music and teasing fill the air.

Expression, Teeth, and the Art of Suggesting Sound

The sitter’s smile is the portrait’s emotional engine. Hals paints it with remarkable subtlety. It is not a fixed grin. It looks like a smile in motion, half formed, shaped by a passing remark or a shared joke. The cheeks lift, the eyes narrow slightly, and the mouth opens just enough to suggest laughter or singing. This is crucial because it makes the portrait feel audible. You can almost imagine the sound of the lute and the chatter of an audience.

Hals’s treatment of the eyes amplifies this effect. The eyes are bright and directed sideways, which conveys social awareness. The sitter is not lost in music alone. He is playing to someone. That social orientation makes him charismatic. It also turns the viewer into an observer of a performance designed for others, which heightens the sense of realism. We are not the only audience. We are stepping into a scene already underway.

The warmth of the face, with rosy cheeks and lively highlights, makes the sitter look flushed with activity. It suggests movement, perhaps drink, perhaps excitement, or simply the energy of performing. Hals uses these cues to give the painting physical vitality.

Costume, Stripes, and the Theater of Identity

The red and black striped costume is bold, even modern in its graphic punch. It immediately signals performance and theatrical identity. In early modern visual culture, striped garments often carried associations with entertainers, outsiders, or figures who lived outside the strict boundaries of respectable dress. Whether the sitter is understood as a musician, a jester like figure, or a lively character type, the costume communicates that he belongs to a world of spectacle.

Hals paints the stripes with confidence, using the strong color contrast to energize the entire image. Red becomes the painting’s dominant emotional color. It suggests warmth, vitality, and playfulness. Against the red, the black creates depth and structure, keeping the costume from becoming chaotic. The result is both decorative and psychologically effective: the sitter’s clothing visually matches his personality.

The cap reinforces the theatrical tone. It sits at an angle, relaxed and jaunty. It makes the sitter look like someone who enjoys attention. Yet Hals avoids caricature by anchoring everything in believable flesh and gesture. The costume may be theatrical, but the face is real.

The Lute as Object and Symbol

The lute is both a musical instrument and a symbol with a long history. In portraits and genre scenes, lutes often evoke harmony, pleasure, courtship, and the art of entertaining. They can also hint at fleeting enjoyment, because music exists only in time. In a culture attentive to moral reflection, images of music sometimes carried a quiet reminder that pleasure passes quickly.

Hals keeps the symbolism open rather than didactic. He does not surround the musician with warning signs or moral emblems. He simply presents the act of playing as a lived moment. The viewer can enjoy the scene at face value while still sensing its fragility. The musician’s smile will fade, the song will end, and the moment will pass. The painting becomes a way of holding that moment still.

The instrument is rendered with convincing weight and surface. The rounded body catches light softly, and the rosette pattern at the sound hole adds delicate detail. Hals does not overwork the wood grain. He suggests the instrument’s presence through shape, light, and tactile realism. The lute becomes a strong visual form that anchors the composition.

Hands and the Impression of Technique

Hands are notoriously difficult in painting, and they are essential here because they must imply music. Hals paints the hands in a way that suggests action without needing precise technical correctness for a specific chord. One hand rests near the strings, ready to strum or pluck. The other holds the neck in a confident grip. The hands feel relaxed rather than stiff, which supports the idea that the sitter is comfortable with the instrument.

The position of the hands contributes to the painting’s sense of immediacy. They do not look posed for a portrait. They look caught mid gesture. This mid gesture quality is what makes the portrait feel like a performance rather than a studio exercise. Hals’s brushwork allows the fingers to remain lively and slightly blurred in their energy, as if motion is implied in paint.

These hands also communicate social identity. A musician’s hands are instruments of skill. By showing them clearly, Hals emphasizes the sitter’s craft. Even if the figure is understood as a character type, the hands make that type believable.

Background and the Focus on Presence

The background is simple and unobtrusive, allowing the figure to dominate. Hals often uses such backgrounds to concentrate attention on expression and gesture. Here, the plain field enhances the sense of proximity. It feels like the musician is close to us, with no deep space behind him. This tightness keeps the portrait intimate and immediate.

The simplicity also highlights color. The red and black costume, the warm flesh tones, and the pale wood of the lute stand out sharply. There is nothing to distract the eye. The painting becomes a study in presence: face, costume, instrument, and the invisible sound implied between them.

This approach also allows Hals’s painterly technique to shine. The viewer can focus on how he models a cheek, how he catches light on a sleeve, how he suggests the curve of wood. The background functions like silence around music, making the main notes more vivid.

Humor, Charm, and the Social Function of Entertainment

The sitter’s expression suggests humor, and humor is central to the painting’s atmosphere. In early modern social life, entertainers were valued for their ability to create communal pleasure. Music, jokes, and playful banter helped bind groups together. Hals captures that social function visually. The musician’s sideways glance implies interaction, and the smile implies shared amusement. We are not seeing solitary art making. We are seeing social performance.

This social dimension is what makes the painting so engaging. The viewer is invited to participate emotionally. Even if you do not know the tune, you can understand the mood. Hals translates sound into expression and gesture. The painting becomes a portrait of sociability itself.

At the same time, the image can be read as a commentary on the pleasures of the moment. The musician’s delight is real, but it is also fleeting. The smile suggests a temporary spark. Hals holds that spark in place, turning a passing expression into something lasting.

Hals’s Brushwork and the Illusion of Life

Hals’s brushwork is a key reason the painting feels alive. He uses confident, economical strokes to suggest form rather than laboriously describing every detail. This technique aligns with the subject, because the subject is about spontaneity and motion. The paint itself seems to move.

The face is handled with sensitivity. Highlights on the cheeks and nose create warmth. Shadows around the eyes and under the hat create depth. The hair is suggested through lively strokes that give it softness and volume. The costume’s stripes are bold and direct, painted with a rhythm that feels energetic. The lute is rendered with controlled simplicity, its large shape and delicate rosette creating a satisfying contrast between broad forms and fine detail.

This combination of painterly freedom and perceptual accuracy is Hals’s signature. He makes the viewer feel that the portrait was painted quickly, in the heat of observation, even though such fluency is the result of mastery.

Why The Lute Player Still Feels So Fresh

The Lute Player remains compelling because it offers a human presence that feels immediate and familiar. The sideways glance, the half laugh smile, and the relaxed handling of the instrument all suggest a person in the middle of life, not posed outside it. Hals captures the charm of performance without turning it into superficial decoration.

The painting also feels fresh because it balances character and realism. The costume may hint at a theatrical role, but the sitter’s expression feels genuine. The work becomes a bridge between portrait and genre scene, between individual likeness and social type. That ambiguity gives it richness. The viewer can enjoy it as a lively depiction of a musician, while also sensing deeper themes about pleasure, sociability, and the fleeting nature of the moment.

In the end, Hals’s achievement is that he paints a mood without reducing it to a cliché. The painting smiles, but it does not feel shallow. It is joyful, but it is not childish. It is a portrait of the energy that passes through music, through laughter, and through the brief connection between performer and audience. Hals preserves that connection in paint, and that is why the image continues to feel alive centuries later.