Image source: artvee.com

Overview of the Composition

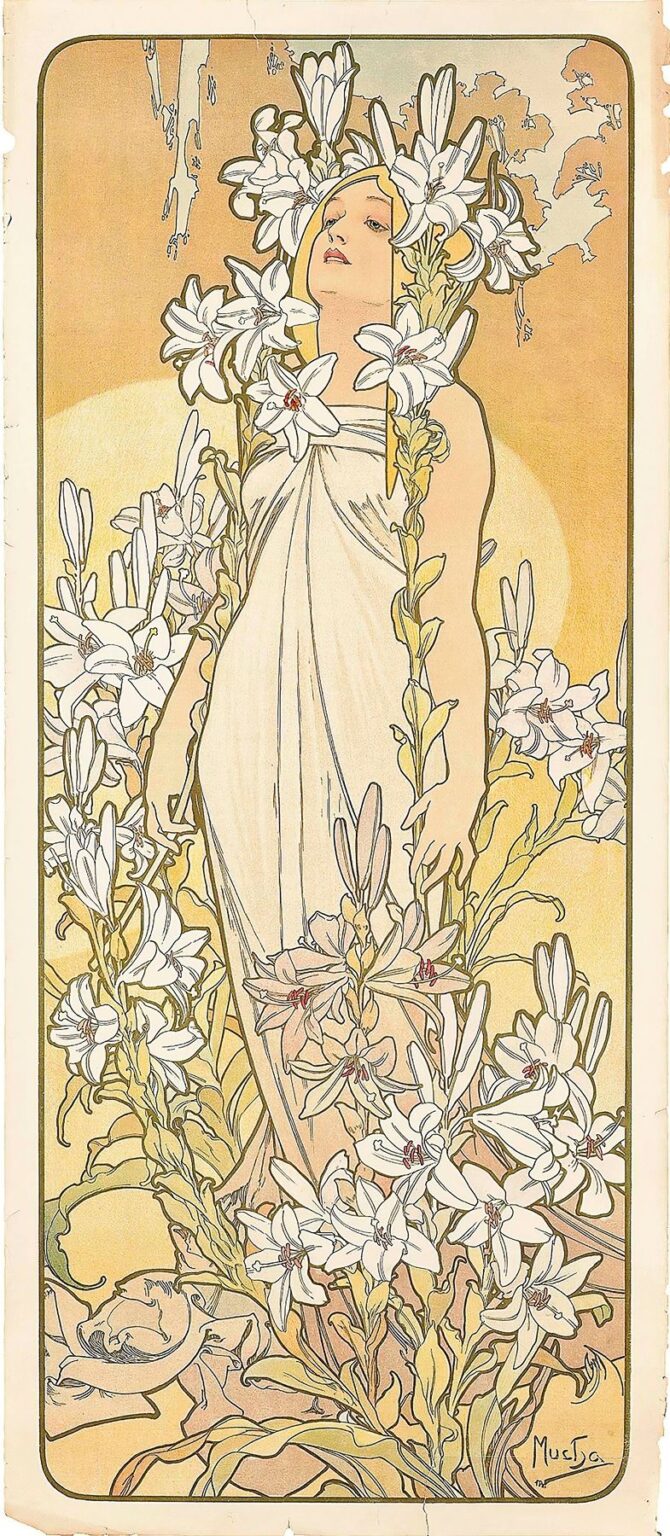

“The Lily” (1897) by Alphonse Mucha is one of the artist’s most celebrated decorative panels from his golden Art Nouveau period. This vertical, narrow-format work features a single female figure who emerges amid a profusion of white lilies, their elegant forms entwined with her presence. The figure’s draped white gown seems to grow organically from the floral stems at her feet, while her upward gaze and slightly parted lips suggest a moment of spiritual awakening or serene transcendence. A radiant, circular halo—suggestive of the sun—looms behind her head, framing her face and linking her to a symbolic solar energy. Mucha’s signature sinuous lines, muted pastel palette, and integrated ornamentation fuse figure, flower, and background into a harmonious whole that epitomizes the ideals of Art Nouveau.

Historical and Artistic Context

By 1897, Mucha had become the poster artist of the Belle Époque, his breakthrough having come two years earlier with the theatrical poster for Sarah Bernhardt’s “Gismonda.” His distinct style—marked by flowing contours, delicate floral motifs, and custom typography—quickly defined the Art Nouveau movement. Parallel to his commercial commissions, Mucha produced a series of decorative “seasons,” “flowers,” and allegorical panels for private patrons and decorative interiors. “The Lily” belongs to this suite of flower-themed lithographs and paintings that celebrated nature’s forms through an idealized feminine presence. Inspired by medieval illumination, Japanese prints, and classical allegory, Mucha’s flower panels sought to elevate everyday botanical beauty into art objects worthy of museums and salons.

Composition and Spatial Organization

Mucha organizes “The Lily” around a strong vertical axis that accentuates the figure’s elongated proportions. The woman stands at the center, her body rising from the bottom of the panel through a cluster of lilies toward the circular solar motif behind her. The flowers at her feet are dense and interwoven, creating a base from which her drapery and the lily stems spring upward. The halo behind her head is off-center—slightly to the right—introducing a subtle counterbalance that prevents the composition from feeling rigidly symmetrical. The background alternates between flat planes of warm gold and soft grayed olive, articulated with fragments of tree silhouettes. This effect establishes depth without resorting to heavy modeling, keeping the overall design light and decorative.

Use of Line and Form

Line is the foundational element of Mucha’s design in “The Lily.” He employs varying line weights to define contours: bold outlines around the figure and blossoms distinguish them from the background, while finer interior lines model the folds of drapery and the delicate veining of petals. The curves of the lily stems echo the sinuous outlines of the woman’s gown and ivory hair, creating a rhythmic interplay of forms. These organic lines guide the viewer’s eye up and down the panel, from the tangle of blossoms at the base through the figure’s poised stance to the solar disc above. The interplay of horizontal, vertical, and diagonal lines generates a dynamic yet harmonious visual flow.

Color Palette and Lithographic Technique

Mucha’s palette for “The Lily” is characterized by soft, luminous hues. Creamy whites dominate the lilies and the figure’s gown, while subdued golds and pale ochres fill the background. Olive-green tones in the foliage and fragments of the sky provide gentle contrast. The use of metallic gold ink in the sun disc and background enhances the poster’s radiant quality. Achieving these subtle transitions required multiple lithographic stones, each laid down with translucent inks. Mucha’s printer, F. Champenois, perfected registration techniques to ensure crisp alignment of fine line work and broad color washes. The result is a surface that appears both flat—as in Japanese prints—and jewel-like, shimmering with layered pigments.

Depiction of the Female Figure

The central figure in “The Lily” embodies both classical beauty and Art Nouveau idealization. Mucha elongates her neck and torso, reminiscent of Gothic statues, while maintaining naturalistic modeling of her face and limbs. Her upward gaze and slightly upturned chin suggest aspiration or communion with the sun’s life‑giving force. Her hair, rendered in strands of pale ivory edged with dark outlines, cascades around her shoulders, blending into the halo’s edge. The draping of her gown, rendered with minimal shading, emphasizes the fabric’s weightless flow. Through this depiction, Mucha presents the woman as an archetype of purity and renewal, her form inseparable from the lilies that frame her.

Symbolism of the Lily

The calla lily has long symbolized purity, rebirth, and spiritual illumination in Western art. Mucha’s choice of the lily aligns with the panel’s solar motifs: the sun disc behind the figure’s head transforms the floral imagery into a broader symbol of life‑giving energy. The dense cluster of blossoms at the base evokes a rich earth from which life springs, while the single vertical stem framing the figure’s right side draws attention to her upward movement. By merging the woman’s form with the lilies, Mucha asserts an essential unity between humankind and nature’s cycles. This symbolic layering invites viewers to interpret the panel as both a celebration of botanical beauty and a meditation on renewal.

Decorative Frame and Border

While “The Lily” lacks a distinct outer border within the panel itself, Mucha’s mastery of decorative framing is evident in the way he uses the solar disc and the fragments of tree silhouettes at the top. The sun disc, with its golden hue and irregular edges, functions as an inner frame for the figure’s head. The mirrored tree silhouettes at the upper corners—rendered in flat, silvery olive—provide a subtle boundary that echoes the panel’s outer rectangular edge. Together, these elements demonstrate Mucha’s belief in integrating ornament into the pictorial space rather than confining it to a separate frame.

Light, Shadow, and Texture

Although the panel presents flat color fields, Mucha suggests depth through localized shading and textural contrasts. The interior folds of the gown receive gentle hatch shading, hinting at the fabric’s volume. Petal edges are defined by thin line work and occasional area of stippling to suggest the velvety texture of lily blossoms. The sun disc’s metallic sheen contrasts with the matte background, evoking a tactile variety that enhances visual interest. This subtle approach to light and shadow allows Mucha to maintain a decorative flatness characteristic of lithography while implying the three-dimensional reality of figure and flower.

Emotional Resonance and Viewer Engagement

“The Lily” captivates viewers through its serene beauty and harmonious integration of human and botanical forms. The figure’s calm yet purposeful upward gaze invites reflection on personal growth and renewal. Viewers drawn to the piece may find in it a sense of peace akin to a sun-dappled meadow of lilies at dawn. Mucha’s ability to evoke these feelings through formal elements—line, color, composition—ensures that the panel functions not only as decoration but also as a source of emotional uplift. The universal symbolism of lilies and the figure’s poised stance create an immediate connection with audiences seeking both aesthetic pleasure and spiritual resonance.

Relation to Mucha’s Flower Series

“The Lily” belongs to a broader series of floral panels that Mucha produced between 1896 and 1900. Others include “The Rose,” “The Daffodil,” and “The Pink Carnation.” Each panel pairs an allegorical female figure with a specific flower, exploring the bloom’s formal and symbolic qualities. In these works, Mucha refines his integration of figure and botanical motif, allowing each flower’s distinctive shape to inform the contours of the drapery and line of the hair. Together, the series became a hallmark of Art Nouveau’s decorative ideals, demonstrating how everyday nature could be elevated into a universal language of form and meaning.

The Influence of Japanese Prints

Mucha’s flat color planes, bold outlines, and cropping of natural forms reflect the influence of Japanese ukiyo-e prints, which he encountered through Parisian print dealers. The asymmetrical balance in “The Lily”—with more floral mass on the left side counterbalanced by the figure’s pose and the halo motif—demonstrates this inspiration. The limited depth cues, emphasis on pattern, and stylized simplification of botanical detail further echo Japanese aesthetic principles. By merging these influences with European allegory and decorative art traditions, Mucha created a hybrid style that felt both modern and timeless.

Technical Challenges and Mastery

Creating “The Lily” required Mucha to adapt the lithographic medium, typically used for advertising posters, to fine-art aspirations. The narrow, vertical format posed registration challenges: each color stone had to precisely align with the previous layers to preserve the continuity of the sinuous lines. The delicate gradations in the sun disc and drapery washes tested the capacities of lithographic inks. Mucha’s close collaboration with the Champenois printing workshop in Paris ensured that the final prints retained the painterly subtleties of his original designs. This technical mastery contributed to the high collectibility of his flower panels and bolstered his reputation as both designer and fine‑art painter.

Legacy and Impact on Decorative Arts

The success of Mucha’s flower panels, including “The Lily,” helped define Art Nouveau’s ornamental vocabulary. Their popularity led to widespread reproduction on ceramics, textiles, furniture panels, and book illustrations. Designers across Europe and North America drew on Mucha’s approach to integrate natural motifs with human forms and decorative borders. The notion of creating a series of decorative panels based on floral allegories influenced movements such as the Vienna Secession and the English Arts and Crafts revival. Even today, echoes of Mucha’s stylized lily forms and sinuous lines appear in branding, packaging, and public art, testifying to the enduring power of his decorative vision.

Conservation and Modern Display

Original lithographic prints of “The Lily” are maintained in museum collections worldwide, often exhibited alongside Mucha’s theatrical posters to illustrate the breadth of his practice. The fragile early papers and layered inks require careful preservation—controlled humidity, low lighting, and acid‑free framing—to prevent fading and deterioration. High‑resolution digital archives and facsimile editions have made the panel accessible to scholars, designers, and enthusiasts globally. Retrospectives of Belle Époque graphics periodically feature “The Lily” as a centerpiece, highlighting its technical finesse and universally appealing aesthetics.

Conclusion

Alphonse Mucha’s “The Lily” (1897) stands as a masterwork of Art Nouveau decorative art. Through harmonious composition, delicate color harmonies, and integrated symbolism, Mucha transforms a simple botanical motif into a transcendent allegory of purity, renewal, and spiritual aspiration. The panel’s seamless fusion of human form and floral imagery exemplifies Mucha’s vision of art as a total decorative experience—one that elevates everyday nature into timeless beauty. More than a decorative panel, “The Lily” continues to resonate as a symbol of hope and harmony in a world constantly in need of renewal.