Image source: artvee.com

Historical and Biographical Context

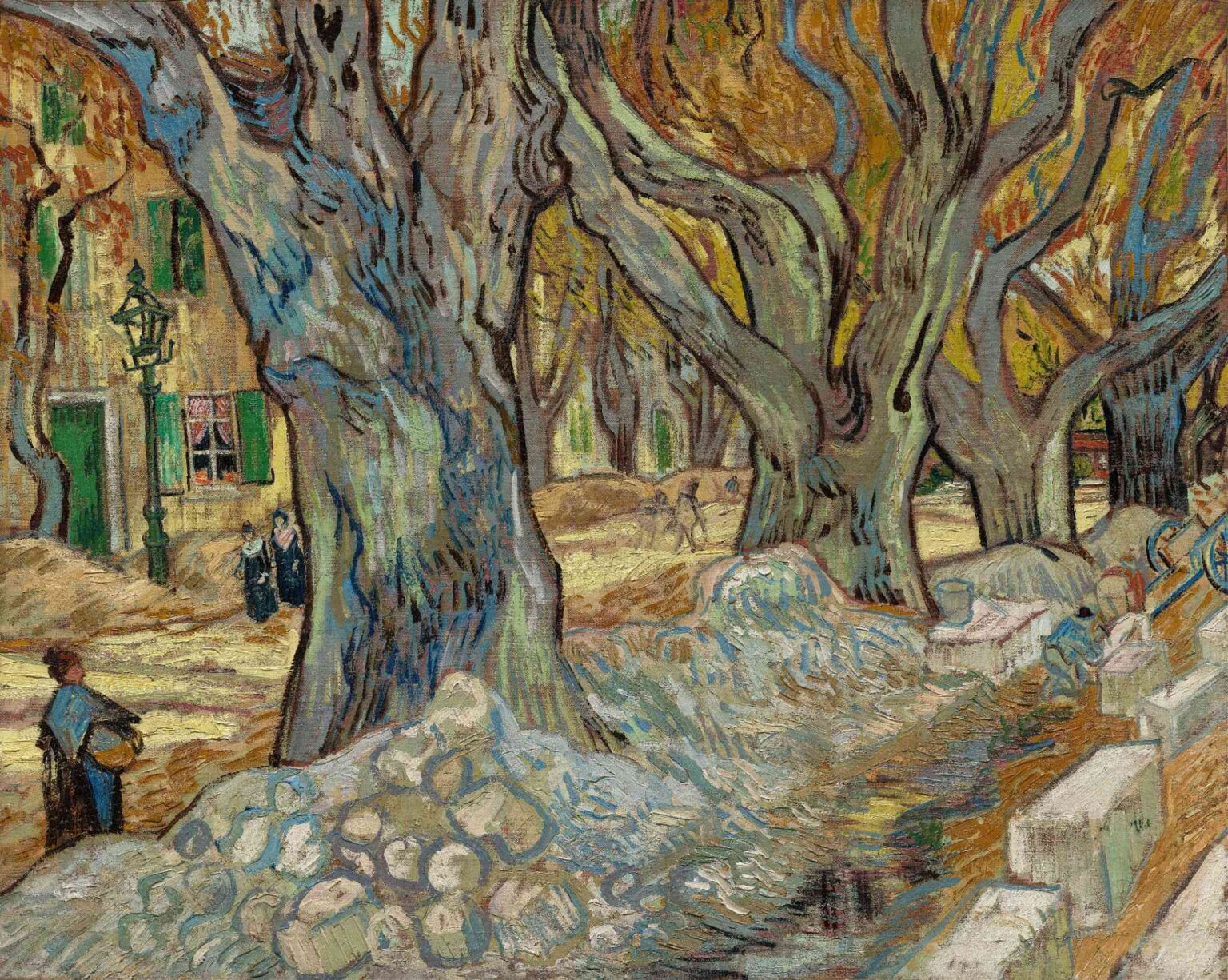

In late 1889, Vincent van Gogh was living at the Saint-Paul-de-Mausole asylum in Saint-Rémy-de-Provence, seeking refuge from the turbulence of his mental health crises. Though confined to the asylum grounds, he painted prolifically, producing some of his most expressive and color-drenched works. “The Large Plane Trees (Road Menders at Saint-Rémy)”, executed in November of that year, forms part of a series depicting the avenues of pollarded plane trees that lined the roads around Saint-Rémy. These massive trees, with their sprawling branches and knotted trunks, fascinated Van Gogh both as sculptural forms and as living monuments to nature’s resilience. In letters to his brother Theo, he described his delight in rendering the interplay of sun, shadow, and architectural rhythm along these tree‐lined avenues.

The Setting: Plane Trees and Road Menders in Saint-Rémy

The painting captures an agricultural scene just outside the asylum walls, where local laborers—road menders—tended the sandy tracks under the canopy of towering plane trees. Van Gogh saw in this quotidian toil a connection between human labor and the natural environment. The trees, pruned into massive, undulating trunks, form an organic colonnade, their thick bases flanked by mounds of road repair materials. Men push wheelbarrows or wield shovels against a backdrop of pale ochre earth, flat fields, and distant cypress groves. Van Gogh integrates the built and the living, portraying workers as integral to the landscape’s seasonal rhythm rather than separate figures.

Composition and Spatial Dynamics

Van Gogh arranges the scene along a strong horizontal axis, with the road stretching from left to right and the tree trunks repeating in rhythmic succession. Yet this horizontal sweep is punctuated by vertical and diagonal countercurrents: the trunks rise skyward, while the billowing branches and the workers’ bent postures introduce dynamic diagonals. The composition’s perspective situates the viewer at a slight angle, engaging us in the labor itself. Unpainted channels at the bottom edge suggest the painting was mounted on a larger canvas, hinting at an originally wider field of view. Through this interplay of directions and crop, Van Gogh conveys both the ordered procession of trees and the improvisational energy of manual labor.

Palette and Chromatic Energy

In “The Large Plane Trees,” Van Gogh employs a robust palette that balances cool and warm tones. The trees’ bark is rendered in swirling grays, blues, and pale greens, their variegated trunks suggesting both solidity and movement. Sunlit earth adopts warm ochres and burnt siennas, contrasting sharply with the deep blue shadows between tree roots. The road menders’ clothing introduces accents of muted blues, grays, and browns, while distant cypresses and undergrowth appear as darker emerald patches. Overhead, the sky is a wash of pale lavender and white clouds, hinting at late autumn’s crisp light. This chromatic architecture underscores Van Gogh’s belief that color itself could carry emotional and spatial information beyond representational fidelity.

Brushwork and Textural Innovation

True to his late-1889 style, Van Gogh builds the painting from vigorous, directional brushstrokes. The trees’ bark is modeled with thick impasto, applied in vertical and diagonal strokes that mimic the ridges and knots of plane trunks. The ground and road are articulated in shorter, hatched strokes of ochre and umber, suggesting the granular texture of dust and gravel. Worker figures are suggested by swift outlines and dabs of paint, their forms barely defined yet fully present through the momentum of brushwork. The branches and sky above receive looser, more fluid strokes, capturing the rustle of leaves and the drifting of clouds. This variety of mark‐making transforms the canvas into a living tapestry where texture and form are inseparable.

Light, Shadow, and Seasonal Atmosphere

Van Gogh captures a moment of diffused light, likely a late autumn afternoon when the sun hangs low, filtering through thinning foliage. Shadows beneath the planes adopt cool purples and blues, while sunlit trunks glow with warm highlights. The road menders operate in half‐shade and half‐sun, their movements partly illuminated. The absence of bright primary hues suggests a season of transition—trees still bear leaves, but the palette has cooled from summer’s intensity. Through his nuanced modulation of light and shade, Van Gogh conveys both the crispness of autumn air and the gentle warmth of Provence’s late-season sunshine.

Symbolism and Thematic Resonance

Plane trees were emblematic of human cultivation of the natural world. In Southern France, these trees were pollarded regularly to line roads and provide shade. Van Gogh saw in their clipped, imposing forms a metaphor for human intervention and nature’s robust capacity for renewal. The road menders, engaged in manual upkeep of communal pathways, mirror the trees’ cyclical pruning and regrowth. Together, tree and laborer embody themes of resilience, stewardship, and the interdependence of man and environment. In Van Gogh’s view, art itself participated in this cycle—brush and canvas pruning away illusion to reveal deeper truths.

Relation to Van Gogh’s Saint-Rémy Series

“The Large Plane Trees” belongs to a rich vein of Saint-Rémy works depicting the asylum landscape: cypress avenues, olive groves, and wheatfields. Unlike the swirling drama of “Starry Night” or the vibrant florals of his asylum garden, this painting emphasizes structure, labor, and seasonal change. It offers a counterpoint to his more fantastical canvases by focusing on everyday work under monumental trees. Together with canvases like “Road with Cypress and Star” and “Olive Trees”, Van Gogh’s Saint-Rémy series explores nature’s formal possibilities and emotional resonance, ranging from intimate studies to grand, visionary compositions.

Technical Examination and Conservation Insights

Infrared reflectography shows that Van Gogh sketched the tree trunks and major pathways in thin charcoal or graphite before overpainting with thick impasto. X-ray fluorescence reveals his characteristic late-palette pigments: lead white, chrome yellow, viridian, cobalt blue, and manganese violet. Microscopic analysis indicates varied impasto heights—the thickest paint appears on the sunlit bark, while backgrounds receive thinner layers. A careful cleaning in the late 20th century removed yellowed varnish, restoring the painting’s original chromatic contrasts and enhancing the vibrancy of shadow hues.

Provenance and Exhibition History

After Van Gogh’s death, “The Large Plane Trees” passed to his brother Theo and eventually to Theo’s widow, Jo van Gogh-Bonger. It was first exhibited publicly in Amsterdam in 1892, then appeared in Brussels (1893) and Paris retrospectives in the early 20th century. By mid-century, the painting had entered a leading European museum collection, where it remains a focal work in exhibitions on Van Gogh’s asylum period. Each showing has underscored the painting’s unique blend of structural form and expressive color, highlighting its significance within Van Gogh’s late oeuvre.

Critical Reception and Scholarly Perspectives

Early critics admired the painting’s formal clarity but often contrasted it with Van Gogh’s more colorful Arles works. Second-generation art historians, however, recognized its psychological depth and technical innovations. Scholars have noted the tension between the imposing plane trunks and the ephemeral labor of road maintenance. Recent studies place the painting within broader discussions of 19th-century landscape modernization, examining how Van Gogh’s depiction of workers converses with contemporary social realities. Neuroaesthetic research further suggests that viewers’ eye movements mirror the rhythmic repetition of tree trunks, indicating an embodied response to the painting’s compositional cadence.

Legacy and Influence

“The Large Plane Trees” has influenced artists exploring the nexus of human labor and landscape structure. Its focus on monumental arboreal forms prefigures Expressionist tree paintings by German avant-garde painters. Contemporary plein-air practitioners draw on Van Gogh’s textural brushwork to depict urban tree-lined avenues and labor scenes. In popular culture, imagery of plane tree alleys often references Van Gogh’s compositional model—strong verticals set against dynamic ground patterns. The painting’s thematic depth and formal energy continue to resonate, inspiring artists to explore the intertwined stories of nature’s architecture and human endeavor.

Conclusion: Monumental Trees and Human Continuity

Vincent van Gogh’s “The Large Plane Trees (Road Menders at Saint-Rémy)” stands as a testament to the symbiosis of art, nature, and labor. Through a masterful composition of repeating trunks, animated brushwork, and a nuanced palette, he transforms a routine roadside scene into a poetic meditation on resilience, stewardship, and seasonal passage. The monumental plane trees, their trunks knotted by pruning and time, echo the enduring capacity of both landscape and human spirit to endure and renew. As viewers traverse the painted road alongside the laboring figures, we are reminded that beauty resides not only in dramatic vistas but in the humble acts that sustain our shared environment.