Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

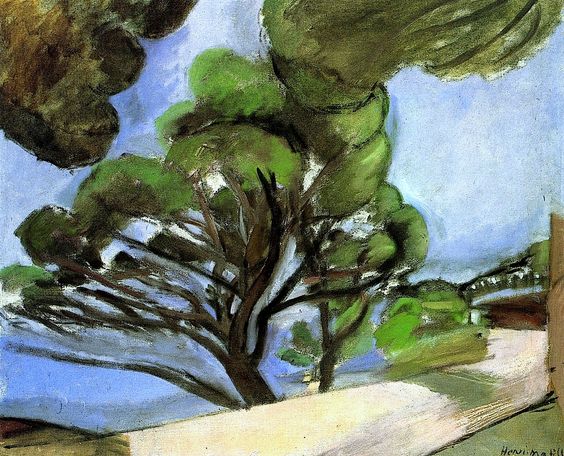

Henri Matisse’s “The Large Pine” (1926) captures the Riviera not as postcard scenery but as a living structure of movement, light, and breath. Painted in his Nice years, this landscape translates the sensation of standing on a sunlit road at Cap d’Antibes while a sea breeze combs through pines. A single tree spreads its umbrella-like crown across the sky, its branches splaying in elastic arcs that seem to push the very air aside. Sand-colored ground tilts toward the viewer; a strip of blue sea slips behind the trunk; distant buildings glint like a handful of pale notes. The picture is frank about its means—broad, loaded strokes; dark, decisive contours; thinly veiled sky—yet the orchestration is delicate. Matisse turns a pine into a conductor’s hand, shaping the entire scene’s rhythm around its swaying gesture.

The Nice Period and the Landscape Recast

Matisse’s Nice period (roughly 1917–1930) is best remembered for interiors and odalisques, but he also used the Mediterranean outside his window as a rigorous studio. “The Large Pine” belongs to the subset of coastal landscapes where he tests how far decorative clarity can go outdoors. Rather than chasing atmospheric detail, he compresses the scene into essential relations: tree versus sky, hot ground against cool water, sweeping curves opposed to gentle horizontals. The result achieves the Nice ambition of sustained calm without sacrificing the experience of living weather. In this painting the wind is visible not as literal leaves in flight, but as elasticities of line and pressure in paint.

Composition as Windborne Architecture

The composition is anchored by the umbrella-pine that dominates the center-left. Its trunk forks and flares, then explodes into layered fans of foliage, each fan a shallow oval edged by firm, breathing contours. Those contours are not prison bars; they are the sprung frames of a tent in wind. Across the top and right the edges of additional boughs enter the frame like parentheses, focusing attention on the central crown and creating a canopy that routes the eye along curving paths. At ground level a pale road angles up from the lower right, meets a dark band of earth, and slides toward the sea—a passage that stabilizes the composition’s airborne upper half. The blue water forms a calm horizontal counter-beat beneath the tree’s swells, and a thin horizon of buildings knits distance with domestic scale.

The Pine as Protagonist and Instrument

Matisse gives the pine the status of a figure. Its trunk reads as spine; its boughs articulate like shoulders and arms; its crown behaves like a head haloed by hair. But this personification isn’t whimsy. It clarifies the tree’s structural role: the pine gathers and distributes forces—the weight of the canopy, the push of wind, the lift of light. Short, muscular branches thrust forward, their blackish outlines thickening and thinning to show torque. The foliage is not feathery. It’s constructed in firm, paddle-shaped masses whose edges alternate between hard and soft, solid and scumbled, as if the air were tugging them. The pine doesn’t decorate the landscape; it organizes it.

Color as Temperature and Depth

The palette is succinct and coastal. Sky is a high, milky blue; water deepens into cooler ultramarines; foliage ranges from moss and bottle green to olive flashes warmed by earth pigments; ground is sun-baked beige modulated with straw yellow and pale gray. Matisse does not employ harsh complements. Instead, he lets warm ground tilt toward the viewer and cool sea recede, while the tree’s greens oscillate between them, creating a hinge that holds the planes together. Blacks are rare and purposeful, used to articulate branch and bough; whites are never sterile but subtly tinted—blue in sky, yellow in sand—so that they participate in the weather of color.

Drawing, Contour, and the Breathing Edge

One of the painting’s signatures is the authority of its drawing. The thick, charcoal-like contours that gird the canopy and branches are neither nervous nor mechanical. They swell and taper in response to form, like a line played on a wind instrument that grows and softens with breath. Where the boughs twist, the line fattens; where foliage thins, the line drops away into scumble and light. Along the road’s edge, a dark boundary turns sharply then dissolves, allowing the ground to lean toward us without falling. These lines do not separate color; they animate it, giving the whole surface a pulse that feels like moving air.

Brushwork and the Evidence of Weather

Matisse’s handling is frank. Wet, loaded strokes form the boughs; faster, drier passes veil the sky so canvas tooth shows through like sun haze. In foliage masses he often drags a lighter value over darker, letting bristles leave tracks that break into needles. The road is brushed thin, a sandy skin where the ground’s weave contributes to the sensation of grit and heat. Paint is not used to mimic bark or leaf; it registers the pressure of gesture—the push and slide of a brush that stands in for wind on forms. That is why the pine seems to vibrate though nothing is literally in motion.

Light, Shadow, and Mediterranean Diffusion

The light is Riviera bright but tempered. Shadows are green-grays and cool browns; they pool on the underside of masses and in the crotch of branches without congealing to black. Highlights are pale, sometimes nearly white, but always warmed or cooled by neighboring color. The sky acts as a gigantic reflector, filling the picture with a clean, breathable radiance. Because contrasts are moderated, the eye can linger; nothing glares. The painting’s brilliance is achieved not through dazzle but through persistent, calibrated luminosity—the Nice-period ideal.

Space, Depth, and Productive Flatness

“The Large Pine” retains enough depth to convince—road receding, water beyond, horizon further still—but its deeper intelligence lives on the surface. Foliage discs interlock like overlapping plates, pressing forward in a shallow relief. Sky shows through in measured intervals, not in random holes; those intervals are compositional breaths. The sea is a single band with subtle value shifts rather than an illusionistic vista. This productive flatness keeps all elements in the same conversation, letting color and contour—rather than perspective tricks—bind tree, road, and sea into a single chord.

Rhythm and the Time of Looking

Matisse composed for the eye the way a musician scores time. The pine’s boughs mark a syncopated rhythm: large arc, smaller counter-arc, pause of sky, repeat. The road’s slanted stripe provides a slower measure; the sea’s horizontal is a sustained pedal note. Viewing becomes listening. The eye loops along boughs, drops to the road, glides across water, and lifts again through the crown. With each circuit, correspondences emerge—a shadow’s cool echoing the sea, a pale sand highlight answering a sky patch, a black branch tracing a path later mirrored by a distant hedgerow.

The Role of Negative Space

The spaces between boughs are not left-overs; they are active wedges of atmosphere that shape the tree’s identity. Matisse trims these gaps with as much care as he draws branches. Some sky pockets are narrow and charged, pushing foliage masses apart like springs; others are larger and restful, giving the eye someplace to land. This calibrated negative space is why the image breathes. It is also why the pine reads simultaneously as a near object and as a map of breezes traced against the heavens.

The Pine as Modern Classical Motif

Classical landscape often uses a tree to frame a view; Matisse modernizes that device by making the frame dynamic. The pine is not a static curtain but an organism whose structure reveals forces—gravity, wind, light—at play. It belongs to a lineage that includes his early Fauvist trees, but the aim has changed. The wild color of Fauvism has been retuned into a lyrical classicism where stability and movement are reconciled. The painting is, in this sense, a landscape of principles: curve balanced by plane, warm by cool, thickness by breath.

Dialogues with Interiors and Other Antibes Views

Although outdoors, “The Large Pine” converses with the Nice interiors. The boughs’ scalloped silhouettes echo the scalloped edges of fabrics; the sky’s pale field functions like a wall papered with light; the road’s angled band behaves as a ground stripe. Compare it with Matisse’s harbor scenes from Antibes and you’ll notice similar solutions: a strong conducting curve; large color fields set in shallow space; accents of dark to articulate structure. The difference is the subject’s voice. Where boats and jetties propose human geometry, the pine offers organic cadence—yet both are orchestrated by the same decorative intelligence.

The Ethics of Simplification

Simplicity here is not reduction for its own sake; it is an ethic of respect for the viewer’s time. By stripping away incidental foliage and textural trivia, Matisse focuses attention on relations that endure. The scene can be re-entered indefinitely without fatigue because its order is structural, not anecdotal. You return for the way the road leans, the bough swells, the sky pocket breathes—not for a one-time narrative payoff. This ethic aligns with Matisse’s long-stated hope that painting might be “a soothing, cerebral influence”—not dulling, but steadied.

Tactile Intelligence and the Sense of Place

Everything in the painting communicates through touch: the weight of branches, the crust of sun-baked sand, the faint drag of brush over canvas mimicking salt air’s resistance. You can feel the slope of the road underfoot and the slackening of pace when shadow crosses it. The sea is near but not theatrically sparkling; it’s a cool panel that promises breeze. The result is not a photographic record of Cap d’Antibes but a concentrated sensation of being there—your body registering curves and temperatures as much as your eyes collect shapes.

Movement Without Blur

One might expect a wind-swept tree to be rendered with flickering strokes, but Matisse avoids literal flutter. Instead he allows contours to swing and masses to lean, building the idea of motion into the bones of the composition. This choice keeps the surface calm while acknowledging the air’s pressure. The painting thus inhabits a balanced time: not the frozen instant of a camera, not the smeared time of motion blur, but the lived interval during which a gust fills branches and passes on.

Why the Pine Endures

A single motif sustains the canvas because it is so well paced. Large shapes carry the main theme; mid-size masses provide counter-lines; small details—dark knuckles of branch, pale slips of sky—keep the chord sparkling. The pine’s silhouette is memorable without becoming emblematic; its internal variations offer endless micro-discoveries. You notice a thin, greenish highlight climbing one bough, then a sudden pocket of cool sky cutting through two masses, then a dark hook of branch tightening the crown’s left edge. Each finding reaffirms the rightness of the whole.

Lessons for Seeing

“The Large Pine” teaches a way of looking at the Mediterranean that resists both postcard prettiness and analytic dryness. It suggests that understanding landscape means feeling the structure of its forces, not counting its parts. It invites the viewer to judge a scene by the truth of its relations: Is the warm ground really answering the cool sea? Does the main curve find its counter? Are there places to rest and places to quicken? By these measures the painting succeeds with ease; it is both restful and alive.

Conclusion

Matisse’s “The Large Pine” turns a roadside view at Cap d’Antibes into a modern classic. A single tree gathers wind, light, and space into a lucid architecture of arcs and planes. The palette is lean and exact; the drawing breathes; the brushwork records weather as pressure, not as anecdote. Shallow space keeps attention on the surface where harmony is built, while enough depth remains for the body to feel present in the scene. The painting doesn’t narrate; it composes. It proposes that serenity is not the absence of motion but the balanced presence of forces—warm with cool, curve with horizon, weight with air. Stand before it, and you breathe at its tempo: slow, alert, sustained.