Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

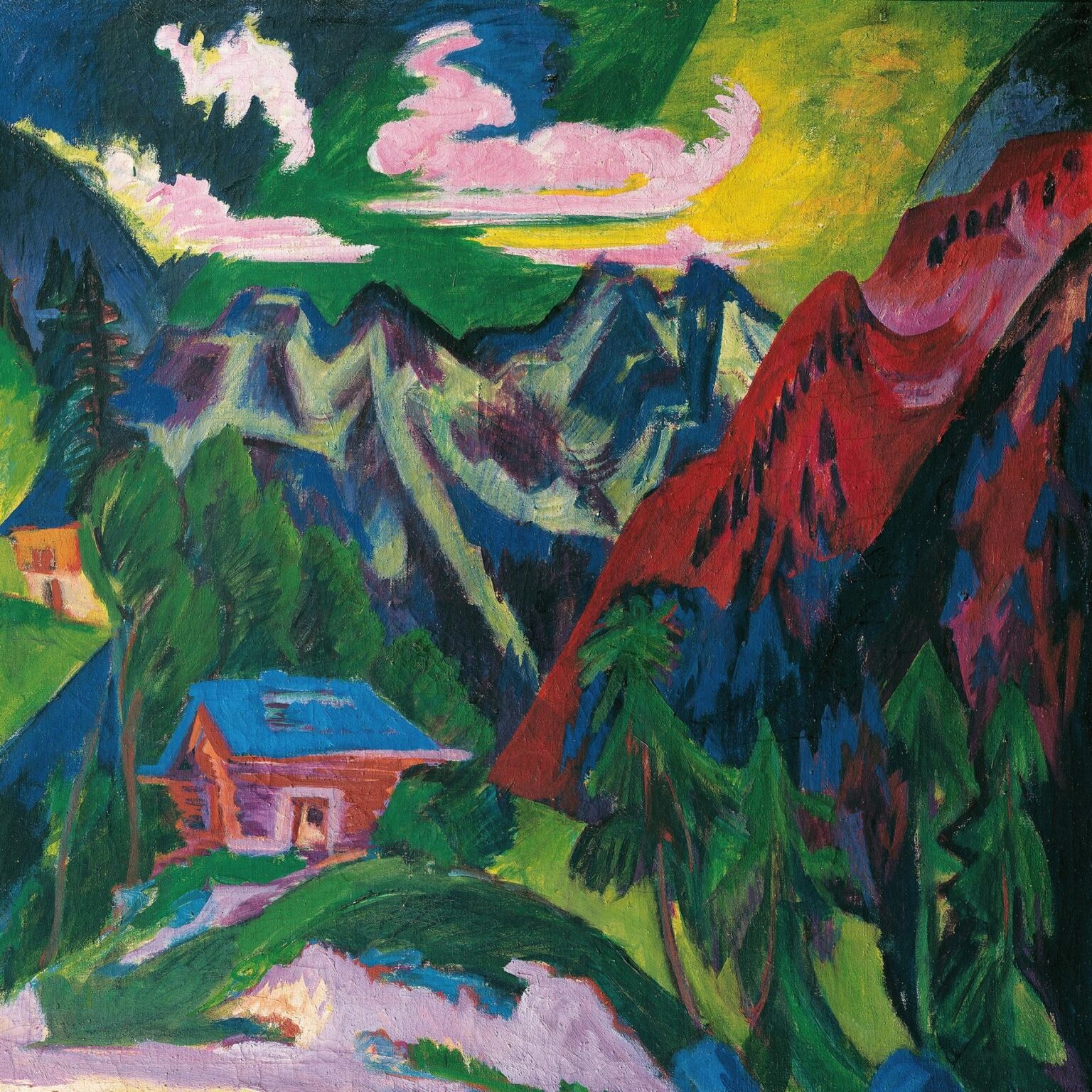

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner’s The Klosters Mountains (1923) stands as a vibrant testament to the artist’s mature Expressionist vision, realized during his years of convalescence and artistic renewal in the Swiss Alps. At first glance, the canvas appears as a riot of color and form: jagged peaks rendered in deep crimsons and cobalt blues, verdant slopes punctuated by conifers, and a solitary alpine hut nestled amid swirling snowbanks. Yet beneath this chromatic exuberance lies a sophisticated interplay of composition, personal biography, and transcendent emotion. Over the course of this analysis, we will explore the painting’s historical and biographical context, its formal strategies in composition and color, its thematic resonance, and its enduring legacy within Kirchner’s oeuvre and modern art at large.

Historical and Biographical Context

By 1923, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner (1880–1938) had already weathered the upheavals of early twentieth-century Europe. Co-founder of the avant-garde Die Brücke group in Dresden (1905), he had championed a radical, emotionally charged aesthetic that rejected academic norms. The outbreak of World War I in 1914 led to Kirchner’s brief military service and subsequent discharge on medical grounds, due to nervous exhaustion and tuberculosis. Relocating to the Davos sanatorium in Switzerland, he found in the Alpine environment both physical relief and new artistic inspiration. The Klosters Mountains—a range visible from his Davos residence—became a recurring motif in his post-war output. In 1923, having acquired greater mastery over his medium and recovered much of his health, Kirchner created The Klosters Mountains, capturing both the rugged grandeur of the landscape and his own spiritual journey toward healing.

The Davos and Klosters Landscape

Davos and the neighboring village of Klosters lie within the canton of Graubünden, a region defined by soaring summits, narrow valleys, and crystalline snowfields. Kirchner’s tuberculosis regimen included daily walks through these mountains, exposure to brisk air, and immersion in natural panoramas. His firsthand experience of the Alpine terrain informed his decision to portray not an idealized view but a lived reality: paths etched by repeated passage, tree stands buffeted by wind, and snowbanks carved by the elements. The Klosters Mountains thus emerges from direct observation, yet Kirchner’s Expressionist temperament transforms this reality into a personal vision, emphasizing psychological resonance over topographical precision.

Composition and Spatial Dynamics

Kirchner arranges The Klosters Mountains around a dynamic spatial schema that both grounds and disorients the viewer. A bold diagonal axis runs from the lower left—where a solitary hut sits amid swirling snow—upward to the right, culminating in the red-toned peak that dominates the canvas. Secondary diagonals—formed by the sloping ridges and the treetops—reinforce this energetic ascent. By compressing foreground and background through overlapping planes of color, Kirchner flattens traditional depth cues, creating a unified pictorial field in which the viewer’s eye travels seamlessly across the surface. The hut, diminutive against the towering summits, serves as a human anchor—a reminder of individual vulnerability amid geological permanence.

Color Palette as Emotional Catalyst

Color drives the expressive force of The Klosters Mountains. Kirchner departs from naturalistic hues, electing instead for a heightened palette: slopes of emerald and olive green cascade into valleys; the mountains’ faces blaze in carmine and indigo; snowfields shimmer in pale violet and cerulean. Above, a sky of lime-tinged chartreuse breaks into streaks of golden yellow and rusty orange, suggesting an otherworldly dawn or dusk. These chromatic contrasts generate a visceral response—viewers feel both the chill of snow and the ardor of sunset. Kirchner’s use of complementary colors—greens against reds, blues against oranges—creates optical vibration, while his daring juxtapositions of warm and cool registers underscore the painting’s emotional dualities: tranquility and tension, resilience and fragility.

Brushwork and Surface Texture

The tactile quality of Kirchner’s brushwork in The Klosters Mountains reveals his deep engagement with material process. Broad, sweeping strokes define the mountain ridges, their heavy impasto catching light and accentuating rugged contours. In contrast, fine, hatched strokes articulate tree clusters and understory foliage, imparting a flickering sense of wind through branches. The snowfields exhibit a mix of scumbled passages—where underlayers of pink and blue peek through thin washes—and more opaque swathes of white that carve out space and volume. Kirchner’s willingness to expose underpainting and embrace accidental overlaps speaks to his Expressionist credo: surface and structure must bear witness to the artist’s hand, and the painting’s facture becomes inseparable from its emotive content.

Integration of Human Presence

The solitary hut in The Klosters Mountains is both literal and symbolic. Its red-timbered walls and steep roof, rendered in simplified geometric form, stand in deliberate contrast to the organic chaos of slopes and sky. The structure marks a site of human habitation—a refuge against the elements and a locus of small-scale domestic life. Yet its diminutive scale underscores human vulnerability within the vast Alpine arena. Kirchner often sought in his Davos years to reconcile the individual with nature, and this hut functions as a visual metaphor for that reconciliation: humanity neither conquers nor retreats, but coexists with elemental forces on terms of mutual respect.

Symbolic Resonance and Psychological Depth

While The Klosters Mountains reads as a landscape, it also operates on symbolic and psychological levels. The rising red peak can be interpreted as an emblem of inner triumph—health regained after illness—or, conversely, as a sign of lingering trauma, the summit forever tinged by past suffering. Snowfields, with their mixture of exposed underlayers and thick white passages, evoke memory’s layered structure: pristine surfaces overlaying complex substrata. The turbulent sky—its unnatural hues swirling like auroral ribbons—suggests a transcendental realm, a reminder that the material world and the spiritual are intertwined. Through these layered symbols, Kirchner transforms the painting into a meditation on healing, mortality, and the search for harmony within adversity.

Formal Innovations and Expressionist Legacy

Kirchner’s Alpine landscapes of the early 1920s, and The Klosters Mountains in particular, contributed significantly to the expansion of Expressionist lexicons. By rejecting linear perspective and naturalistic chroma, he foregrounded subjective perception, paving the way for later abstract and Neo-Expressionist movements. His integration of thick and thin strokes, his embrace of visible underpainting, and his bold color juxtapositions influenced contemporaries such as Emil Nolde and Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, as well as later artists exploring the emotional potential of landscape. Kirchner’s technique in this painting anticipates mid-century experiments in gestural abstraction—underscoring the capacity of paint itself to convey psychological states independent of representational fidelity.

Viewer Engagement and Emotional Impact

Encountering The Klosters Mountains is an immersive, almost sensorial experience. The compressed space and kinetic diagonals draw viewers into the Alpine terrain, as though standing at the hut’s doorstep, looking up at a sky ignited in unnatural light. One senses the crisp chill of snow underfoot while detecting the warm afterglow of the sun on rugged peaks. The painting’s oscillation between warm and cool registers engages the viewer’s body as much as the eye, generating a synesthetic response to color and form. Kirchner’s deliberate flattening of depth invites viewers to traverse the canvas as a unified emotional landscape, rather than as a mere topographical depiction.

Place in Kirchner’s Oeuvre and Alpine Series

Within Kirchner’s broader output, The Klosters Mountains occupies a crucial position as a mature alpine work that synthesizes his Expressionist fervor with the introspective calm of his Davos years. Earlier Alpine pieces—such as the haunting winter woodcuts of 1918–1919—grappled with trauma and isolation. By 1923, Kirchner had regained a measure of physical strength and artistic confidence, allowing him to approach the landscape with both reverence and creative boldness. The Klosters Mountains thus represent a culmination: the painter’s ability to channel personal history, environmental immediacy, and formal innovation into a resonant whole. Subsequent works would continue to explore mountain vistas, but few match the compositional unity and emotional complexity of this masterpiece.

Influence on Subsequent Generations

Kirchner’s alpine landscapes, epitomized by The Klosters Mountains, helped legitimize landscape painting as a conduit for existential inquiry. His challenge to representational norms inspired artists within the Neue Sachlichkeit movement to explore realism’s psychological dimensions, and later informed Abstract Expressionists’ engagement with gesture and color-field. In post-war Europe, painters such as Georg Baselitz and Anselm Kiefer revisited the terrain of memory and place, drawing upon Kirchner’s precedent of embedding personal and collective histories within landscape. Today, The Klosters Mountains continues to be studied not only for its Expressionist innovations but also for its testament to art’s capacity for healing and transcendence.

Conclusion

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner’s The Klosters Mountains (1923) transcends its initial guise as an Alpine landscape to become a profound exploration of human resilience, artistic invention, and the emotional power of color and form. By marrying bold composition, a daring palette, and textured brushwork, Kirchner crafts a painting that resonates on multiple levels: topographical, psychological, and symbolic. The solitary hut anchors the viewer in a world both vast and intimate, while the surging mountains and electrified sky evoke the perennial dance between vulnerability and strength. As a landmark of mature Expressionism, The Klosters Mountains affirms Kirchner’s legacy as a pioneer who channeled personal adversity into visionary art, leaving a lasting imprint on the trajectory of modern painting.