Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

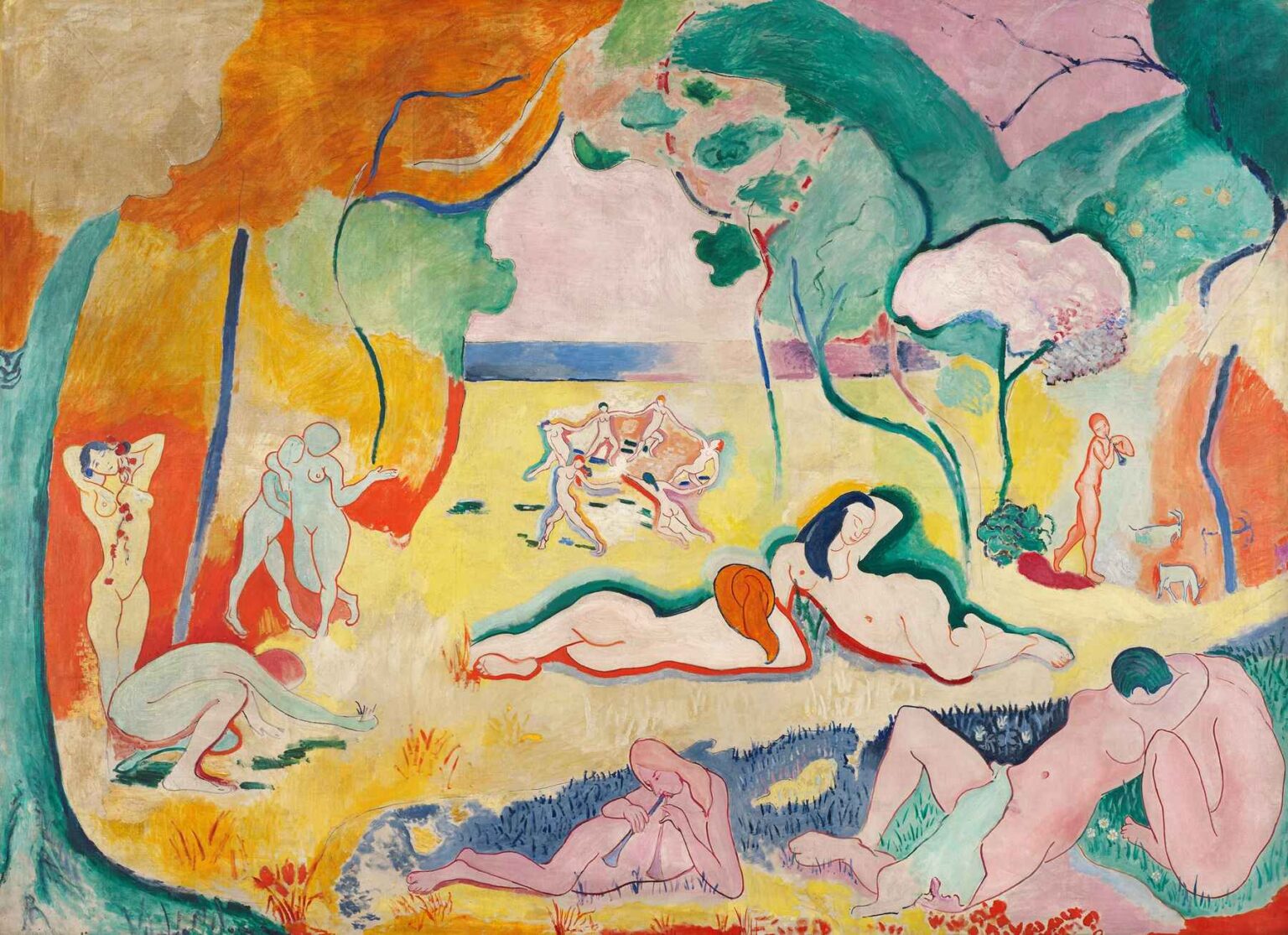

Henri Matisse’s The Joy of Life (1905–1906) stands as a cornerstone of early modernist painting, heralding the bold chromatic innovations of Fauvism and redefining the possibilities of pictorial expression. Measuring nearly two meters in height and three meters across, this monumental canvas depicts a pastoral arcadia populated by nudes dancing, reclining, and playing music within a vividly colored landscape. When first exhibited at the Salon d’Automne in Paris in 1905, it scandalized critics with its “wild” palette yet captivated fellow artists with its daring formal freedom. Over a century later, The Joy of Life remains a powerful testament to Matisse’s vision of art as a celebration of color, form, and human vitality. In this analysis, we will explore the work’s historical context, compositional structure, use of color and light, treatment of the figure, spatial dynamics, thematic undertones, emotional resonance, brushwork techniques, and its enduring influence on twentieth-century art.

Historical Context

Painted on the eve of World War I, The Joy of Life emerges from a period of profound experimentation and upheaval in European art. By 1905, Matisse had already made his name alongside André Derain and Maurice de Vlaminck as a leading exponent of Fauvism, a movement defined by its radical use of non-naturalistic color and simplified forms. The term “Fauve,” meaning “wild beast,” was first applied derisively by critic Louis Vauxcelles, yet Matisse and his peers embraced the label as a badge of creative freedom. Rejecting the muted palette and academic traditions of nineteenth-century painting, they sought to convey emotional and sensory experience through pure color. The Joy of Life represents the apogee of this project: a synthesis of decorative pattern, flattening of space, and joyous figuration. At the same time, the painting reflects Matisse’s interest in non-Western art, especially African sculpture and Islamic art, whose influence can be seen in the rhythmic lines and ornamental motifs that animate the canvas. This convergence of avant-garde impulses and cross-cultural inspiration positioned The Joy of Life as a radical statement of modern art’s potential.

Composition and Structure

At first glance, The Joy of Life appears as a pastoral idyll, yet its composition is anything but pastoral in a traditional sense. Matisse divides the canvas into three roughly horizontal zones. The foreground features reclining figures on grass rendered in patches of blue and green. The middle ground reveals dancers and musicians arranged along a sinuous diagonal, while the distant horizon and sky occupy the upper band in soft pinks and purples. Within this tripartite framework, Matisse introduces vertical accents—tree trunks painted in bold blues and blacks—that pierce the horizontal flow and create a gentle tension. The dancers themselves form a semi-circular chain near the center of the canvas, their linked arms evoking both ritualistic unity and centrifugal energy. There is no single focal point; instead, the viewer’s eye travels freely across the rhythmic alternation of figures and landscape elements. By subordinating perspective to decorative arrangement, Matisse creates a tapestry-like effect where color and line guide the gaze more than realistic spatial recession.

Use of Color and Light

Color in The Joy of Life performs a dual function: it conveys spatial relationships and evokes emotional resonance. Matisse applies saturated hues—vibrant oranges, fuchsias, emerald greens, and cerulean blues—in broad, flat planes. Shadows dissolve into complementary color fields rather than modeling form through chiaroscuro. The grass under the reclining figures, for example, is not depicted as a single mass of green but as interlocking patches of deep blue and chartreuse, suggesting both volume and decorative pattern. The sky’s lavender-pink gradient bathes the scene in a warm, ethereal glow, while the distant hills are rendered in cool greens that recede optically. Matisse’s color choices frequently defy local realism: tree trunks are cobalt blue, a nude figure’s flesh may be tinged with peach or pale violet, and the distant horizon is often outlined in fuchsia. This freedom from naturalistic color heightens the painting’s emotional charge, turning the landscape into a stage for pure sensation.

Figure Treatment and Anatomy

The human figures in The Joy of Life are at once representational and abstracted. Matisse simplifies anatomical detail to essential contours, often outlining limbs and torsos with a single calligraphic stroke. Facial features receive minimal attention—two dots for eyes, a short line for mouth—emphasizing the universal over the individual. Yet despite this economy, each pose conveys a distinct mood: the reclining nudes exude languid repose, the circle of dancers embodies communal ecstasy, and the lone flute player suggests introspective solitude. The figures’ proportions are deliberately varied: some appear elongated, others squat, reflecting Matisse’s priority of compositional harmony over anatomical accuracy. Their interaction with the landscape is seamless; bodies nestle against the ground as if sculpted from the same colored planes, reinforcing the unity of human and nature.

Space and Perspective

Matisse rejects traditional Western perspective in favor of a flattened pictorial field. There is no single vanishing point; instead, depth is suggested through overlapping shapes and color shifts. The receding band of dancers, drawn smaller and painted in cooler hues, implies distance without precise linear recession. Tree trunks overlap figures, creating foreground cues, yet they lack tapering or converging lines. The horizon is indicated by a simple horizontal line of pale blue, above which the sky occupies a shallow rectangle. By collapsing depth into decorative strata, Matisse turns the canvas into a mosaic where spatial logic yields to rhythmic pattern. This approach not only liberates color and form but also invites viewers to engage with the painting as an abstract composition as much as a figurative scene.

Symbolism and Themes

Although The Joy of Life is not overtly narrative, it resonates with symbolic undertones drawn from classical and mythological sources. The circle dance at the center recalls the Bacchanalian revelries of antiquity, suggesting themes of fertility, community, and the ecstatic union between humanity and nature. The juxtaposition of solitary figures—a pipe player, a flute player—alongside group dancers highlights the spectrum of individual introspection and collective celebration. The pastoral setting evokes Edenic connotations of innocence and harmony, yet Matisse’s arbitrary color choices remind us that this is no literal Arcadia but a realm of imagination. The painting’s very title, The Joy of Life, positions it as an affirmation of art’s capacity to capture the exuberance of existence, transcending the limits of rational representation.

Emotional Resonance

More than a decorative marvel, The Joy of Life generates a powerful emotional atmosphere. The warm glow of the sky contrasted with the vivid hues of earth and foliage produces a sense of twilight—a fleeting moment suspended between day and night, consciousness and dream. This liminal quality infuses the dancers’ movements with both exuberance and melancholy, as if celebrating life’s ephemeral beauty. The reclining figures, in turn, evoke restful contentment, their postures suggesting languorous reflection rather than physical exhaustion. Matisse balances these moods through his color harmonies: complementary pairs such as orange and blue create visual vibration, while analogous hues—yellow and green—soothe the senses. The cumulative effect is a painting that feels alive with joy, yet tinged with a poignant awareness of life’s transience.

Technique and Brushwork

Matisse’s brushwork in The Joy of Life ranges from broad, flat applications to animated, calligraphic lines. Large color fields—such as the ochre grass and purple sky—appear almost planar, applied with a steady, even hand. By contrast, the outlines of figures and trees are executed with swift, confident strokes that retain the artist’s hand gesture. There is minimal impasto; instead, Matisse often allows the canvas tooth to show through thinly applied paint, lending the surface a luminous quality. In areas where colors meet, he sometimes leaves a narrow buffer of unpainted canvas or a contrasting contour, reinforcing the autonomy of each hue. This method underscores the painting’s decorative surface while preserving the vibrancy of individual strokes.

Influence and Legacy

Upon its debut, The Joy of Life polarized critics but profoundly influenced younger artists. Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, encountering its flattened space and bold color, found ammunition for their nascent Cubist experiments. In the decades that followed, Matisse’s emphasis on decorative rhythm and abstract form resonated through movements as diverse as Orphism, Color Field painting, and the Pattern and Decoration movement. Contemporary painters continue to draw on The Joy of Life as a model for integrating figuration within abstracted, decorative surfaces. The painting’s blend of joyous subject matter and avant-garde technique remains a touchstone for artists seeking to reconcile emotional expressiveness with formal innovation.

Conclusion

Henri Matisse’s The Joy of Life endures as a masterpiece of modernist painting—a canvass where exuberant color, simplified form, and expressive brushwork converge to celebrate the human spirit in harmony with nature. Rejecting the conventions of perspective and naturalistic representation, Matisse constructs a luminous world governed by rhythm and chromatic interplay. Through his bold formal choices, he transforms a pastoral scene into an implacable vision of art’s capacity to evoke joy, wonder, and communal vitality. More than a period piece, The Joy of Life stands as a lasting affirmation of painting’s power to transcend the mundane and to articulate the deepest yearnings of the human heart.