Image source: artvee.com

Introduction to “The Iris” by Alphonse Mucha

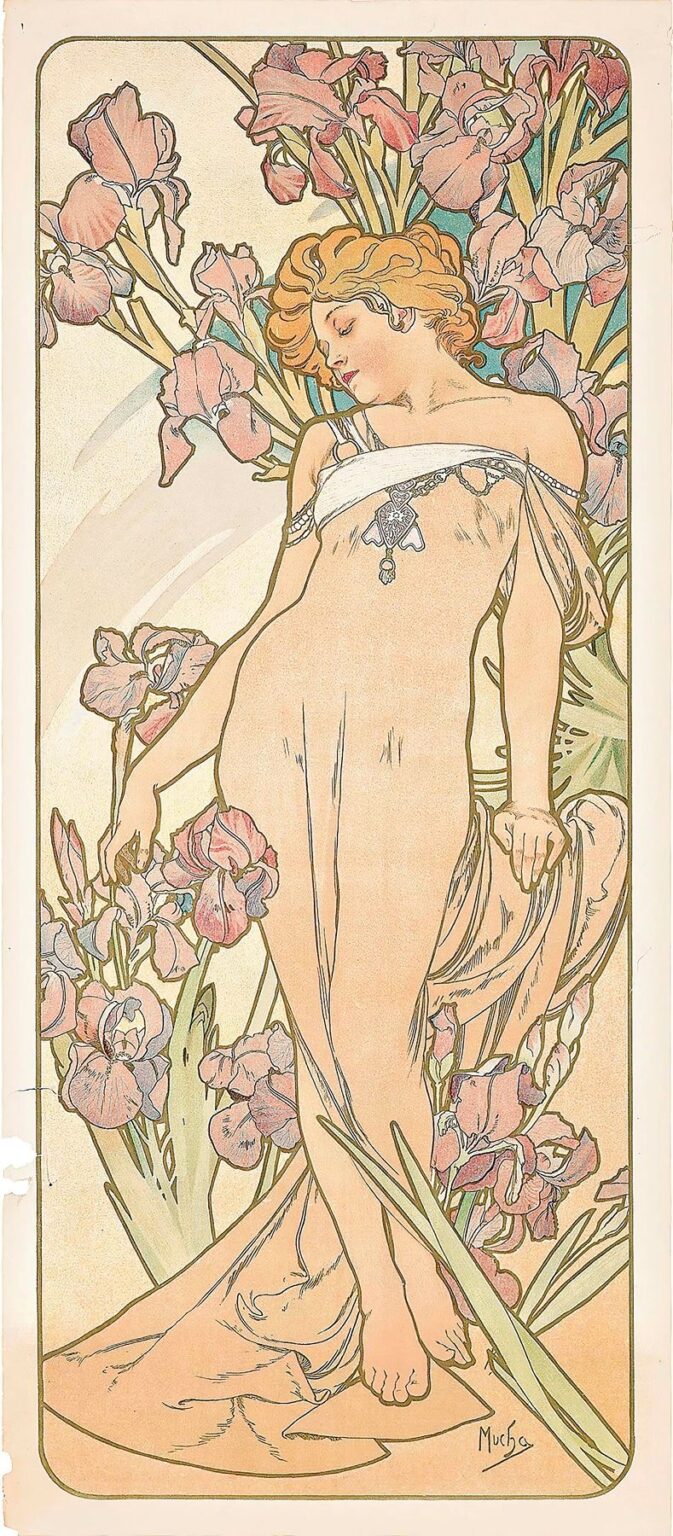

Alphonse Mucha’s The Iris (1897) stands as one of the most iconic flower‑panels in the artist’s celebrated series of botanical allegories. Executed at the height of Mucha’s Art Nouveau fame, The Iris combines his trademark sinuous line work, subtle pastel palette, and integrated ornamental framing to present an idealized female figure emerging from a tangle of iris blooms. Although originally conceived as a decorative lithograph, the work transcends its commercial origins to become a timeless study in form, color, and symbolism. In this in‑depth analysis, we will explore the historical context, compositional structure, symbolic resonance, technical mastery, and enduring legacy of The Iris by Alphonse Mucha, demonstrating why this 1897 masterpiece continues to captivate art enthusiasts and collectors worldwide.

Historical and Cultural Context of 1897

The late 19th century in Europe was a period of tremendous aesthetic innovation. Art Nouveau, as a movement, sought to break free from the rigid historicism of academic art and to infuse design with organic forms drawn from nature. Mucha emerged as the poster‑artist par excellence following his breakthrough 1894 commission for Sarah Bernhardt’s “Gismonda” poster. By 1897, he had established a Parisian studio producing posters, decorative panels, and designs for fashion and interior decoration. The Iris was created at a moment when urban audiences were hungry for beauty in everyday life—on tramway cars, shop windows, and printed ephemera. Molly Miller, in her Art Nouveau, notes that Mucha’s flower‑panels “perfectly encapsulate the era’s yearning for aesthetic unity between art and nature.” Thus, The Iris can be seen as both a commercial product and an emblem of turn‑of‑the‑century ideals.

Alphonse Mucha and the Art Nouveau Movement

Mucha’s career interwove poster design, decorative painting, and book illustration, all underpinned by a guiding Art Nouveau ethos. Characterized by elongated figures, flowing drapery, and stylized botanical ornament, his work shaped public expectations of modern graphic art. Unlike the more geometric Jugendstil of Germany or the Secession in Vienna, Mucha’s style remained rooted in natural forms and classical allegory. His flower‑series, including The Iris, The Rose, and The Lily, exemplified this synthesis. As design historian Sarah Wilson argues, “Mucha’s lily and iris panels transformed ephemeral prints into enduring art objects, illustrating that advertising could be as elevated as gallery painting.” In this context, The Iris emerges as a signature fusion of Mucha’s aesthetic principles and the broader aspirations of Art Nouveau.

Commission, Publication, and Audience

Although Mucha accepted many theatrical and commercial poster commissions, his flower panels were often self‑initiated or produced for private patrons. The Iris first appeared as a color lithograph published by F. Champenois in Paris. Subscribers to Mucha’s decorative series would receive these panels for home display, effectively turning living rooms into curated Art Nouveau salons. The audience for The Iris was therefore both the cultured urban bourgeoisie and the more mainstream consumer drawn to the novelty of colorful, nature‑inspired prints. The widespread distribution of lithographic editions ensured that Mucha’s floral allegories—once confined to walls of cafés or theater districts—became accessible across Europe and America, further cementing his reputation.

Composition and Visual Structure

At first glance, The Iris presents a narrow, vertical composition dominated by the central figure and surrounding blooms. Mucha arranges the panel along a strong vertical axis: the woman’s graceful posture rises from her feet at the bottom, through her draped torso, to her lifted head near the top. Iris flowers flank her on either side, their long stalks and semi‑opened buds creating a rhythmic pattern that echoes her elongated form. Behind her, a flattened circular halo provides a unifying focal point, subtly delineating space without resorting to heavy perspective. The overall spatial structure is thus a dynamic interplay of vertical, diagonal, and circular forms, guiding the viewer’s eye through a continuous loop around the panel.

Sinuous Line and Decorative Contours

One of Mucha’s defining techniques is his masterful use of line—varying in weight but unwaveringly elegant. In The Iris, the contours of the figure’s body, her flowing drapery, and the iris stalks are all drawn with a confident, unbroken stroke. Interior details—such as the folds in the fabric and the petals’ veins—are rendered in finer lines that suggest texture without obscuring the overall shape. This calligraphic approach derives in part from Japanese ukiyo‑e prints, which Mucha studied and collected. By combining bold outer lines with delicate inner lines, Mucha achieves both graphic impact and tactile nuance, a hallmark of his Art Nouveau style.

Color Palette and Lithographic Technique

Mucha’s color palette in The Iris is both restrained and evocative. Soft peach and cream hues define the figure’s skin and drapery, while muted greens provide foliage accents. The iris flowers themselves appear in gentle shades of mauve and pink, their softly graduated petals capturing natural variation. Mucha employs metallic inks—particularly for the circular background halo—to introduce a subtle luminosity. Achieving these effects demanded painstaking multi‑stone lithography: each color requires its own stone, carefully registered to preserve crisp outlines and layered washes. The translucent inks overlap to create nuanced tones, giving the lithograph a painterly depth that transcends mere flat printing.

Depiction of the Central Figure

The female figure in The Iris embodies both classical beauty and idealized femininity. Mucha elongates her proportions—long neck, gently curved shoulders, and extended limbs—evoking Gothic sculpture and Hellenic statuary. Her pose is at once relaxed and poised: one foot steps lightly forward, as if emerging from the floral undergrowth, while her head tilts slightly downward in a contemplative gesture. Mucha’s careful modeling of her face—soft transitions of color, subtle shadows under her chin—imbue her with a serene, almost otherworldly presence. She becomes an allegory of purity and renewal, her form inseparable from the lilies that surround her.

Symbolism of the Iris Flower

Beyond its formal beauty, the iris carries rich symbolic associations. In Western art, the iris often signifies hope, wisdom, and spiritual faith. Its three prominent petals were linked to the Christian Holy Trinity, while its regal hues conveyed dignity and mystery. Mucha harnesses these connotations in The Iris, pairing the flower with a figure whose modest drapery and upward gaze suggest introspection and enlightenment. The iris stalks at her feet ground her in nature’s cycles of growth and rebirth. In this way, Mucha’s iris allegory gestures toward both personal transformation and broader cycles of life, resonating with turn‑of‑the‑century interests in mysticism and symbolism.

Light, Shadow, and Texture

Although Art Nouveau posters are celebrated for their flat planes of color, The Iris reveals Mucha’s sensitivity to light and texture. The drapery receives gentle gradations—achieved through layered lithographic washes—that suggest the weight and sheerness of fabric. Petal edges, where line meets color, show minimal shading but employ halftone screens to imply surface texture. The background halo uses metallic gold ink to simulate the sun’s radiance, while the pale tree silhouettes at the top of the panel recede into a misty, dreamlike atmosphere. Together, these treatments of light and shadow enrich the viewer’s sensory experience without sacrificing the poster’s graphic clarity.

Decorative Border and Ornamental Harmony

Mucha’s dedication to total decoration is evident in subtle border treatment. A thin, rounded‑corner rectangular frame encloses the central scene, its inner edge highlighted by a slender band of muted olive. This simple border contrasts with the complex interior, ensuring that the viewer’s focus remains on the figure and flowers. At the bottom and top, narrow bands of pale gold accentuate the panel’s vertical format without overwhelming the composition. Mucha’s restraint in border design allows his signature ornamental motifs—flowing drapery lines, botanical forms, and circular halos—to shine within a unified decorative schema.

Emotional Resonance and Viewer Engagement

The Iris engages viewers not merely through aesthetic delight but through emotional resonance. The figure’s serene expression, the interplay of soft colors, and the rhythmic repetition of iris forms evoke a gentle sense of calm and renewal. Viewers are invited to imagine themselves walking through a dawn garden, each iris bloom echoing a moment of personal awakening. Mucha’s integration of form, color, and allegory transforms the poster from simple decoration into a contemplative experience. The emotional power of The Iris lies in its ability to merge the everyday—flowers we might pass on a stroll—with the transcendent ideals of beauty and rebirth.

Influence on Decorative Arts and Poster Design

The Iris played a pivotal role in establishing Art Nouveau’s decorative principles across Europe and America. Its success as a lithographic panel encouraged architects, interior designers, and textile artists to incorporate floral allegories and sinuous lines into their work. The concept of pairing an idealized female form with a specific flower became a template for countless posters, book covers, and decorative objects well into the early 20th century. Mucha’s seamless blend of function and decoration in The Iris demonstrated that commercial art could attain the status of fine art, influencing generations of graphic designers and illustrators.

Conservation, Reproduction, and Legacy

Original lithographs of The Iris are highly sought by collectors and museums, yet the fragile early 20th‑century papers and layered inks demand careful conservation. UV‑filtered lighting, climate control, and acid‑free framing protect these delicate prints from fading and deterioration. High‑resolution digital reproductions have made Mucha’s iris panel accessible to scholars and design enthusiasts worldwide. Continued exhibition in major retrospective shows, alongside publications exploring Art Nouveau’s global reach, ensures that The Iris remains a touchstone for understanding the decorative innovations of the Belle Époque.

Conclusion

Alphonse Mucha’s The Iris (1897) embodies the essence of Art Nouveau’s harmonious union of nature, symbolism, and human form. Through refined composition, masterful line, and luminous color, Mucha elevates a simple floral motif into an allegory of purity, renewal, and spiritual awakening. The panel’s enduring appeal lies in its seamless integration of decorative art and emotional resonance, making The Iris not just a product of its time but a timeless exemplar of design excellence.