Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

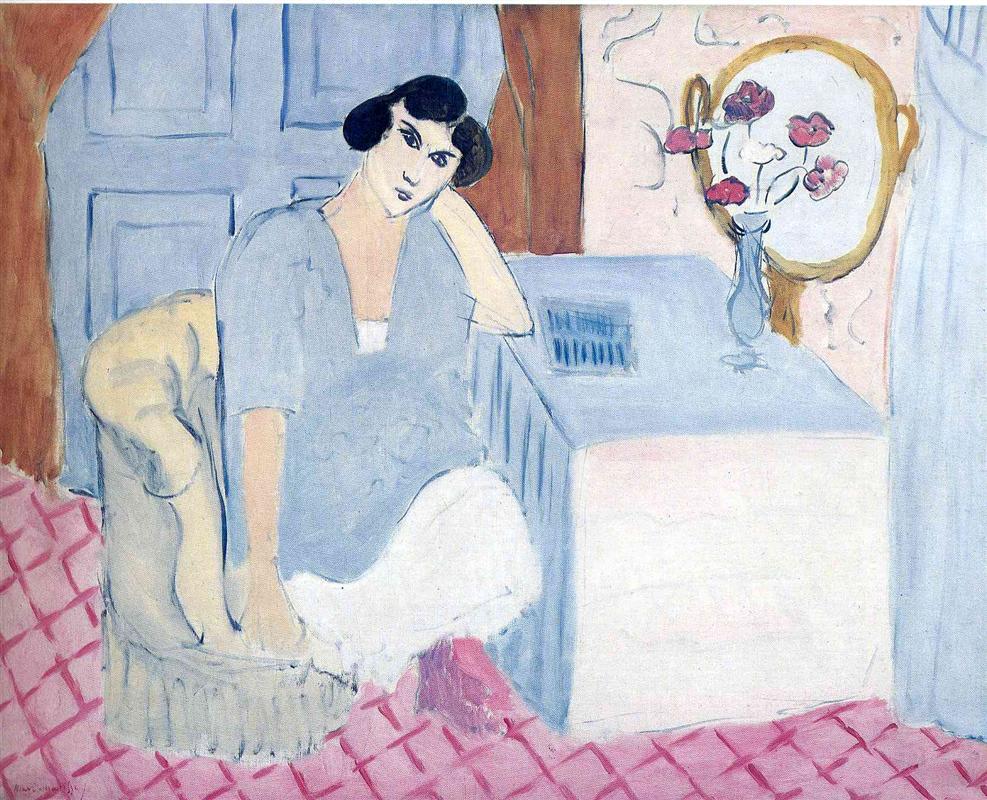

Henri Matisse’s “The Innatentive Reader” (1919) turns a familiar domestic scene into a crystalline orchestration of color, line, and space. A woman sits in a pale blue room, her cheek propped on her hand, a book resting somewhere between attention and neglect. A mirrored oval reflects a small vase of poppies. The tiled floor flashes a pink lattice that pulls the eye toward the central table, where a cool, chalky light settles. Nothing overtly dramatic happens, yet the painting radiates presence; Matisse transforms idleness into a rigorous study of how color creates mood and how a few architectural planes can hold an entire world in place.

The Nice Period Context

The canvas belongs to Matisse’s early Nice period, painted just after World War I when he pursued a renewed clarity. He had explored the blaze of Fauvism and the angular experiments of the 1910s; in Nice he pivoted toward a measured lyricism. Interiors, shutters, patterned floors, mirrors, and quiet figures became instruments for testing light. “The Innatentive Reader” distills that program. Instead of salon grandeur or psychological probing, the work offers a domestic chamber tuned like a musical chord, where each color is a note and every contour is a beat that organizes the whole.

First Impressions and Motif

At first glance, the scene is simple. A woman in a soft blue dress sits forward on an upholstered chair, her head tipped to her hand in a classic gesture of reverie. The room is all pale values: blue paneled doors behind her, a white and light-blue table before her, a powdery wall with a mirror hanging like a golden moon. Within the mirror you see poppies and stems—real flowers in a nearby vase, displaced and doubled. A pink floor patterned with slanting diamonds animates the lower half of the canvas. The book is present but quiet, a rectangle of darker blue near the table’s edge; its smallness, compared with the large fields around it, explains the title’s gentle irony.

Composition as Stagecraft

Matisse composes with the confidence of a theatre director. The doors at left form a steady, vertical backdrop. The table extends from the right edge diagonally into the room, establishing a central platform for light to rest upon. The figure occupies the hinge between door and table, her bent arm echoing the oval of the mirror; even her hairstyle repeats the room’s calm curves. A large shape—the pale upholstery of her chair—anchors the lower left, while the right is stabilized by the cool rectangle of the table. The floor’s lattice pulls the eye inward and then releases it toward the tableau of the mirror. Overlap supplies depth: chair before wall, figure before chair, table before mirror. The space is shallow enough to honor the painted surface yet deep enough to feel habitable.

Color Architecture and Temperature

The palette is a poised negotiation between cool and warm. Blues and blue-grays dominate the doors, dress, and table; they carry the room’s breath and establish a calm key. Into that cool field Matisse sets precise warm accents: the pink of the tiled floor, the ocher rim of the mirror, the coral-lipped poppies, and the blush that touches cheek and cushions. Whites are never blank; they lean cool or warm depending on the neighbor they face. Black appears sparingly in hair, lashes, and a few linear notations, giving structure without heaviness. Because each color family recurs in multiple areas—the blue of dress repeats on the doors and book, the pink of floor returns in flowers—relationships replace description, and harmony becomes the subject.

Light Without Spectacle

The light is Mediterranean yet carefully moderated. No theatrical spotlight breaks the composure; instead, a wide, even illumination allows volumes to turn by temperature. The table’s top holds the brightest value, a plane of near-white coolness that throws everything else into gentle relief. Flesh gathers warmth on forehead and cheek and turns cooler near jaw and throat. The doors’ panels retain brushy highlights that keep them from ossifying into flat decor; the mirror’s ring glows softly, as if catching light from a window outside the frame. The result is a steady climate of seeing in which attention can linger.

The Figure: Gesture over Psychology

The reader is not pinned to a biography. Her face is abbreviated, the modeling restrained. The gesture—cheek in palm, elbow on knee—communicates a pause rather than a mood, a readiness to drift rather than brooding weight. Matisse avoids the traps of anecdote; identity yields to placement. She is the node that knots together the wall’s verticals, the table’s diagonals, and the floor’s lattice. Her dress, a field of soft blue, supplies the picture’s largest cool plane; by gently varying its temperature, he prevents the figure from flattening and keeps her alive inside the chord.

The Mirror’s Double Work

Mirrors in Matisse are not purely devices of illusion; they are compositional engines. Here the oval hangs like a golden buoy against the pink wall. It reflects a vase and poppies, compressing still life and room into one poetic sign. The reflected bouquet echoes the woman’s tilted head, and the oval’s curvature converses with the curve of her arm and chair. This doubling accomplishes two tasks. First, it introduces a second center of interest without cluttering the table. Second, it foregrounds the act of seeing: we witness a reflection that the sitter may or may not notice, a subtle reminder that interiors contain more than one way of looking.

The Pink Lattice Floor

The floor matters. Its pink tone, worked with loose diagonal strokes that crisscross into a diamond pattern, energizes the lower half and establishes the painting’s warm foundation. The lines converge toward the table, guiding our gaze without literal perspective vanishing points. Because the floor is the broadest warm field, it permits the rest of the room to remain cool without slipping into chill. Matisse often relied on such patterned grounds in Nice; they act like musical rhythm sections, steadying the tempo so melody—figure and mirror—can float.

Drawing and the Living Contour

Line is the quiet hero of the canvas. Matisse’s contour is elastic, thickening where he needs weight—along the chair’s turn and the jawline—and thinning where he wants softness—at the dress’s neckline and sleeve. He draws with color as much as with black; edges transition from gray-blue to pink to white, and the viewer feels the pressure of each stroke. The effect is to keep the form breathing. Even the book is only partially enclosed by line, a rectangle suggested by tonal shifts and a handful of marks. This “living contour” replaces descriptive fuss with clarity.

Brushwork and Surface

The paint is candid, sometimes thin, sometimes more loaded. The doors are laid in with broad, parallel strokes that let the weave of the canvas show through, giving the plane a chalky openness. The dress receives softer, scumbled passes to suggest cloth. The poppies are achieved with a few loaded dabs; the eye accepts their petals because the color interval is tuned, not because each flower is counted. The floor is brushed briskly; the diagonal strokes never lock into mechanical perfection, keeping the room awake. Everywhere the surface remembers how it was made, turning the act of painting into part of the content.

Materials and a Likely Palette

A compact palette underwrites the harmony. Lead white constitutes much of the room’s light and the table. Ultramarine and cobalt blues drive the doors, dress, and book, cooled further with white or tempered with a breath of black for gray-blue panels. Yellow ochre warms the mirror rim and lives in the underpaint of the floor, where it mixes with red lake or cadmium red light to achieve the coral-pink of the tiles. Viridian or a blue-leaning green touches leaves in the reflected bouquet. Ivory black stays disciplined, reserved for eyelashes, hair accents, and defining lines. Thin and opaque passages alternate, allowing air to circulate through the paint film.

Rhythm and the Eye’s Path

The painting invites a repeatable loop of looking. You begin at the woman’s eyes, travel along the diagonal of her forearm to the table, pause at the cool flare of its top, continue to the mirror’s oval and the poppies within, and then drop down the right edge where the table’s vertical pleats bring you back to the floor. The lattice lines carry you leftward to the chair and upward to the figure again. Each circuit reaffirms rhymes: oval mirror to bent arm; blue table to blue doors; poppy red to floor pink; cool whites of table to cool whites at the dress’s hem. Rhythm supplants narrative; the painting holds attention by keeping the eye in motion.

Attention, Distraction, and Meaning

The title’s playful misspelling—“Innatentive” rather than “Inattentive”—only sharpens the theme. The reader’s attention is not absent; it is ambient. She is held by the room’s slow light, by the cool of blue planes and the warmth pulsing through the floor and flowers. The book becomes one element among many in a broader composition of perception. Matisse offers a modest ethics of looking: attention is not a narrow beam but a balanced field. In 1919, such balance reads as a deliberate choice against agitation and for a carefully tuned calm.

Comparisons within 1919

Placed alongside Matisse’s balcony scenes and bedroom reflections from the same year, this painting appears cooler and more pared down. Where other Nice interiors feature shutters flung open to the sea or a riot of patterned textiles, “The Innatentive Reader” relies on a small number of broad planes. The mirror stands in for a window, offering an interior “view” that remains inside the room. The figure’s dress, rather than an ornate kimono or striped robe, is a quiet blue field. This spareness lets the structure of color relations come forward without competition.

The Human Scale of the Room

Everything in the canvas is proportioned to the body. The table is just high enough to lean upon; the chair supports a pose that could last for minutes; the mirror hangs at a height that captures flowers and perhaps, if she leaned back, a glimpse of the sitter herself. Even the floor pattern feels calibrated to the stride. The space is not a set for spectacle but a place designed for habit. Matisse suggests that beauty belongs in the scale of human living, not only in vistas or grand gestures.

How to Look, Practically

Stand close and let the blue of the doors resolve into many blues, each panel breathing slightly differently. Move to the mirror and notice how the poppies are both brushwork and bloom. Step back to feel the table’s top become a single plane of light; watch how the book darkens at the edge, anchoring the composition. Let your gaze travel the lattice of the floor until the rhythm becomes physical. Return to the figure’s face; see how little is required—a few strokes for eyelids, a blush at the cheek—for presence to happen. The painting rewards such slow scanning; it is built for return.

Conclusion

“The Innatentive Reader” is one of Matisse’s clearest demonstrations that a painting can be calm without being inert. With a handful of planes—blue doors, white-blue table, pink floor—and a figure tuned to those planes, he composes a room where color and light support attention rather than demanding it. The book may be neglected for a moment, but looking is not. The viewer completes the chord, moving through the room in time, noticing how reflection, pattern, and pose keep answering one another. In the end, the painting reads like a held breath that never strains: a durable, crystalline quiet.