Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

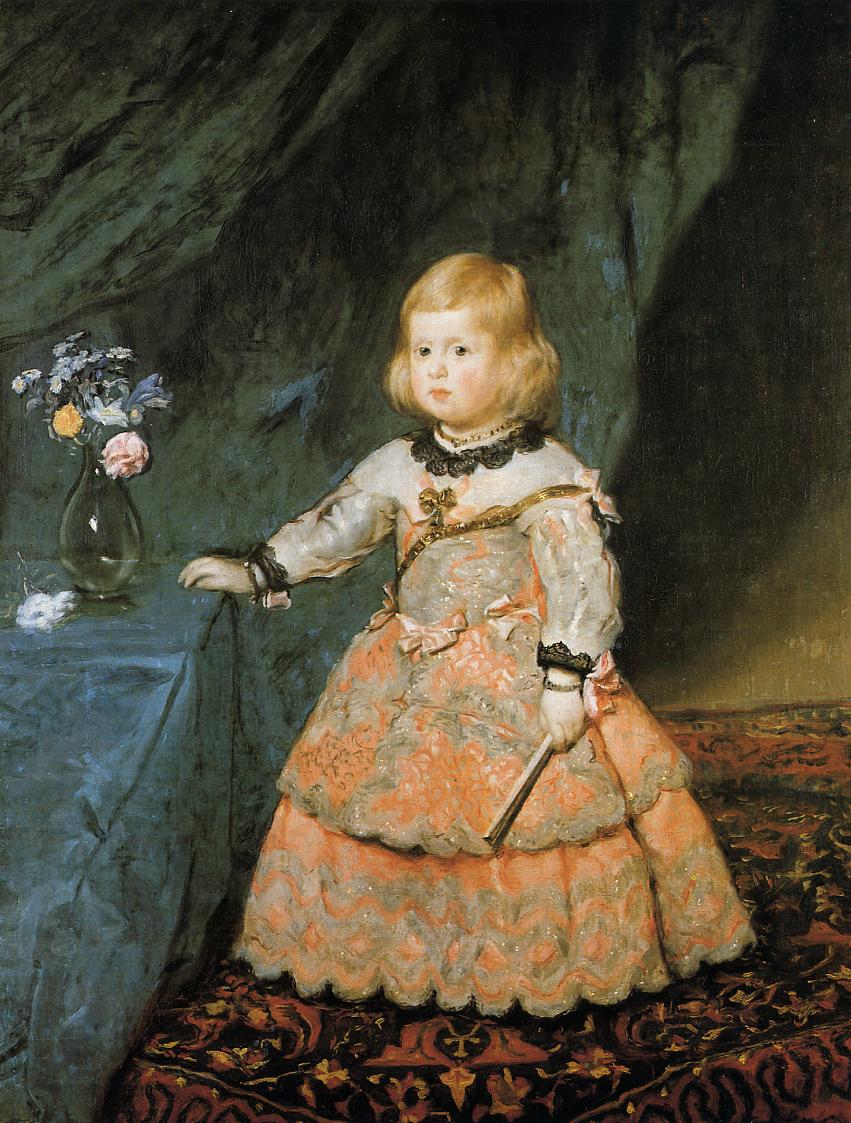

Diego Velázquez’s “The Infanta Margarita Teresa of Spain in a Red Dress” (1653) presents one of the Spanish court’s most beloved children at the threshold of public identity. The small princess stands on a patterned carpet, her right hand touching a blue-draped table set with a glass vase of flowers, while her left hand holds a tiny closed fan or baton. A monumental dress of coral-red and silvery gray expands around her small frame. Behind, a dark green curtain rises like a theatrical backdrop, creating an intimate stage where light, air, and the featherweight gravity of childhood meet the protocols of royalty. With his late, economical brush, Velázquez transforms a ceremonial likeness into an encounter charged with presence.

A Child at the Center of Court and History

Margarita Teresa, daughter of Philip IV and Mariana of Austria, would become the radiant center of “Las Meninas” a few years later. In 1653 she was a toddler and already a dynastic symbol, her image destined for foreign courts as negotiations circled possible Habsburg matches. Velázquez, who had just returned from Rome with a freer touch and a heightened sense of atmospheric unity, faced a dual task: to show a child schooled in etiquette and to let the viewer meet a person still new to the world. This painting fulfills both aims with restraint and candor. It is the record of a royal childhood that was also a public office.

Composition and the Architecture of Small Majesty

The composition is built on a firm geometry that dignifies the diminutive sitter. The triangular fall of the curtain, the rectangular thrust of the table, and the broad oval of the skirt interlock to stabilize the figure. Margarita stands slightly left of center, turned three-quarters toward us, head aligned with the glowing axis of the tablecloth and vase. The carpet’s repeating pattern forms a visual ground that supports the expanded dress and keeps the child from floating in space. Velázquez uses these shapes to enlarge presence without falsifying scale; a tiny person occupies a balanced stage and therefore commands it.

Light, Palette, and Tonal Breath

Light enters from the left, crossing the tablecloth’s cool blue, sparking the flowers, and then washing softly across the child’s face and dress. The palette is a poised harmony of cool and warm: coral-reds and apricot notes in the gown’s brocade, silvery grays in the overlayer, deep green in the curtain, blue in the tablecloth, and earth hues in the carpet. These colors are not flat fields but temperature gradients. Blue breaks into turquoise where it thins on the table edge; green darkens to nearly black in the curtain’s folds; the red dress shifts from salmon lights to burnt-orange shadows. The atmosphere is continuous—every object shares the same air—which is why the portrait reads as a real moment rather than a staged diagram.

The Dress as Language Rather Than Inventory

Court costume in mid-seventeenth-century Spain could overwhelm a portrait with detail. Velázquez refuses enumeration. The scalloped hems and embroidered patterns are rendered by rhythmic, broken strokes; the metallic trims flicker as small highlights rather than counted threads; ribbons are swift accents that change hue as the light turns. The dress is convincingly opulent, yet nothing feels labored. This painterly economy preserves the child’s primacy. We sense fabric weight and richness, but the eye returns to the face.

The Face and the Poise of Early Self-Possession

Margarita’s features are built with tender planes rather than hard lines: a luminous forehead, rounded cheeks with a faint rose bloom, a small mouth held in unshowy composure, and eyes brightened by minute points of light. The expression is neither decorative nor solemn; it is the quiet seriousness of a child performing stillness for adults. Velázquez never sentimentalizes. He registers the discipline required to stand and be looked at, and he allows a soft alertness—almost curiosity—to temper the formality.

Gesture, Fan, and the Vocabulary of Courtly Conduct

The right hand’s light touch on the table gives balance and creates a bridge between figure and setting. The left hand holds a small fan or baton, a customary accessory that taught children how to manage gesture within layers of stiff fabric. Velázquez paints it with a few precise strokes so it reads immediately without diverting attention. These controlled movements narrate etiquette: deportment learned young, poise rehearsed until it looks effortless.

Table, Vase, and Flowers as Optical Counterpoints

The still life at left is brief and brilliant: a delicate glass holds blue and pale pink blossoms, their stems seen through the liquid with a few greenish lines. The tablecloth’s cool plane offsets the warmth of the dress and brings the child forward through contrast. The tiny bouquet has symbolic connotations—innocence, transience—but it also serves a straightforward pictorial purpose: a cluster of cool, high notes that keeps the composition from collapsing into red and green.

The Dark Curtain and the Theater of Air

Rather than furnish a recognizable room, Velázquez gives the portrait a curtain that behaves like a painted sky: it swells and recedes, catching light along ridges and sinking into near-black valleys. This background creates a breathable void where the sitter’s presence can expand. It also belongs to the court’s repertoire of representation—an allusion to ceremony—yet here the curtain is subordinated to air. Space supports character; it never competes.

Brushwork and the Art of Necessary Paint

At close range the picture is a grammar of purposeful marks. The carpet’s arabesques are calligraphic loops that resolve into pattern at distance. The brocade is a dance of interlaced reds and grays; where the brush is dragged dry, the texture imitates woven threads. The curtain is built from long, sweeping strokes; the blue tablecloth is laid in broad planes that break at edges to reveal the ground. Flesh is handled more tenderly, wet transitions joining cheek to jaw to throat. This variety of touch—bravura for fabric, delicacy for skin—keeps the image alive without noise.

Childhood Framed by Ceremony

The central tension of the portrait lies in scale: an immense costume encases a very small body. Velázquez makes the dress an architecture Margarita inhabits rather than a spectacle that swallows her. The scalloped tiers step downward like a theater’s seating; the bodice holds the torso upright; the sleeves project volume that the tiny hands punctuate. The painter honors the reality of court life—children rehearsed in adult codes—yet he protects the child’s interiority with silence around the face. The result feels both ceremonial and tender.

The Habsburg Image and Velázquez’s Frankness

The Habsburgs commissioned portraits that circulated across Europe as political currency. Velázquez served those needs while maintaining a clear-eyed standard. He neither idealizes nor exposes. Margarita’s physiognomy is recorded with care, but atmospheric transitions keep features from hardening into caricature. The painter’s honesty becomes the sitter’s dignity: truth, not flattery, underwrites authority.

Comparisons with Later Images and “Las Meninas”

This early portrait anticipates the commanding center of “Las Meninas” (1656), where Margarita appears slightly older, surrounded by attendants and the painter himself. Here, as there, breathable darkness, calibrated whites, and conversational gaze create a presence that overpowers props. Later workshop portraits of Margarita often multiply ornament; Velázquez’s own hand prefers suggestion over accumulation. The difference is the difference between spectacle and insight.

The Viewer’s Distance and the Contract of Regard

We meet Margarita at a distance that feels like a private audience. The painter positions us just below her eye level, so she retains a measure of sovereign height despite her size. Her gaze addresses us frankly but without theatrics. The contract is mutual respect: the child will hold still; the viewer will attend without prying. That pact—so characteristic of Velázquez’s late manner—explains why his royal portraits feel modern. They treat looking as a moral act.

Material Truth and the Trace of Time

The painting’s surface preserves its making. Thin places in the curtain reveal warm undercolor; thick lights on the dress and flowers catch real light in the gallery; faint craquelure traces the darker fields. Velázquez allows these records to remain because they are part of truth: the sitter’s life and the paint’s life share the same object. As time passes, those material traces heighten the portrait’s intimacy.

Symbolic Echoes Without Heavy Allegory

Elements carry symbolic resonance yet never weigh the picture down. Flowers suggest innocence and the passing of time; the carpet’s richness announces the court’s resources; the fan signals etiquette; the curtain implies ceremony. But symbolism is always secondary to optical fact. The portrait persuades through how things look—the sheen of silk, the softness of hair, the clarity of glass—so that meaning arises from perception rather than from inscription.

The Modernity of Restraint

Velázquez’s late style anticipates later realist portraiture by trusting atmosphere and touch over emblem. Here, restraint is everything: a limited palette, an unfurnished space, and a refusal to catalog costume. What remains is presence—small, poised, undeniably real. In a world saturated with images of power, the quiet conviction of this canvas still reads as radical.

Why the Image Endures

“The Infanta Margarita Teresa of Spain in a Red Dress” endures because it solves a difficult problem with grace: how to render a ceremonial child both as symbol and person. It does so by orchestrating a small number of elements—carpet, table, flowers, curtain, dress—around a gaze that feels alive. The painter’s economy lets viewers finish the image with their own attention, which is why the portrait continues to reward looking centuries later.

Conclusion

This painting is a masterclass in how Velázquez converts court ritual into human encounter. Margarita stands small within a large world of fabric and expectations, yet the painter gives her a zone of calm air in which to appear. Cool blue, deep green, warm red, and quiet flesh tones harmonize; brushwork ranges from calligraphic bravura to whispering transitions; formality never crushes tenderness. The result is both a dynastic document and a work of psychological modernity. In the hush of the dark curtain and the shimmer of the red dress, a child who would become an emblem of Spain meets us with simple, unforgettable presence.