Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

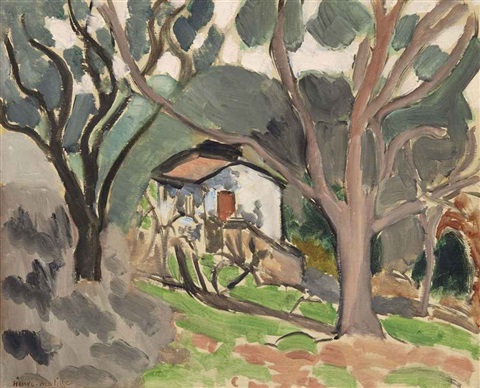

Henri Matisse’s “The House” (1919) captures a modest dwelling glimpsed through a web of tree trunks and boughs. The building is pushed back into the middle distance while the foreground surges with curving branches and patches of earth and grass. The composition feels at once intimate and theatrical: a viewer stands at the edge of a grove, gazing through a shifting lattice of limbs toward a tiny architecture bathed in light. What might have been a straightforward landscape becomes an inquiry into how line, color, and rhythm can transform a simple scene into a living structure. Painted shortly after the First World War and during Matisse’s so-called Nice period, the canvas combines a softened Fauvist palette with the artist’s lifelong interest in arabesque contour, decorative surface, and the poetry of everyday subjects.

Historical Context: 1919 And A Return To Quiet Motifs

The year 1919 is a hinge in European life and in Matisse’s career. The Armistice has ended years of devastation, and artists across France are turning toward rebuilding—culturally and psychologically. Matisse, who had already tempered the fiery extremes of Fauvism, embraced subjects that promised continuity and repose: interiors, studio corners, window views, and small patches of landscape. “The House” belongs to this restorative impulse. Instead of trumpeting triumphal urban scenes, Matisse chooses a humble dwelling half hidden by trees. The choice reads like a pledge to ordinary life, an affirmation that stability and shelter remain essential after collective rupture. The painting’s calm gravity suggests not nostalgia but renewal: the world is not spectacular, but it is habitable.

The Motif: A Modest Dwelling As Emotional Anchor

At the center sits the house, a small structure with a pitched roof and simple wall planes. It is barely more than a rectangle capped by a triangle, with a red-brown door or shutter set within. Its geometry is firm but unpretentious. Crucially, the house is not foregrounded; branches and trunks mediate our approach. This retreat from the obvious focal point turns the building into an anchor rather than a spectacle. It holds the center of the painting the way a tonic note holds a piece of music. The house also carries symbolic weight: a figure of shelter, privacy, persistence, and the human mark within nature. Matisse lets it be quiet so that its significance can resonate.

Composition: A Screen Of Trees And A Window Of Space

The design is built around a screen. Large trunks occupy the right and left margins, while smaller branches sweep across the upper half of the canvas. These dark, calligraphic limbs create an arch that frames the house and directs the gaze inward. At the same time, they flatten the space, reminding us that we are looking at paint, not simply through it. Matisse’s composition oscillates between depth and surface: the curved limbs establish a near plane like a theatrical proscenium; the opening they form becomes a window through which the house and slope of grass appear. The exceptional clarity of the central void—light gray sky, pale walls—contrasts with the denser, darker contours that surround it. The result is a steady visual pulse: closed, open, closed again.

Rhythm Of Line: Arboreal Arabesques And The Calligraphic Hand

Matisse’s drawing is never merely descriptive; it is musical. In “The House,” the trees are defined by sinuous lines that swell and taper like notes. The limbs are simplified into arabesques that curl and double back on themselves, especially at the canopy where rounded clumps of foliage nestle against the sky. These lines do more than outline forms. They produce rhythm across the surface, setting up a tempo that the eye follows from trunk to bough to twig. One can almost feel the artist’s wrist moving—decisive, economical, yet responsive to the particularity of each curve. Even fallen branches on the ground echo the larger arcs above, binding earth and sky with a common gesture.

Color And Light: A Mediterranean Tonality Toned To Quiet

The palette is restrained and luminous. Greens range from minty grass to olive shadow, while the earth reads as cool umber and violet-tinged brown. The house walls are warm gray, a reflective plane that receives a soft bath of light. The roof introduces a muted terra-cotta accent, echoed by the small red door or shutter, which pricks the center like a heartbeat. Matisse avoids high-key clamor; instead he doses color with care so that relationships, not single notes, carry the feeling. The greens and grays sit side by side in broad planes, often meeting along brush-drawn contours rather than blended transitions. Light is not theatrical sunlight but an even, temperate brightness—perhaps late winter turning to spring—leaving pockets of cool shade in the understory.

Brushwork And Surface: Speed, Economy, And Present Tactility

While the drawing provides scaffolding, the brushwork supplies breath. Leaves are handled as rounded patches of opaque paint, their edges left fresh and unlabored. Trunks are laid in with plump, slightly modulated strokes that record the drag of the bristles. On the ground, broader swathes of color sweep diagonally, suggesting undulations in the terrain without slavish description. Matisse’s touch is confident enough to leave decisions visible. Where another painter might smooth or glaze, he prefers to let a single stroke stand for a branch, a shadow, or a patch of sky. The surface therefore reads as a present tense; we sense the painting being made, not polished into an illusion of seamless nature.

Space And Perspective: Shallow Depth Built From Overlap

There is perspective in “The House,” but it is not the vanishing-point geometry of academic landscapists. Depth emerges by overlap: a near trunk cuts across a mid-distance trunk, which in turn cuts across the wall of the house. The ground plane climbs the picture surface in tilted bands, compressing distance. The sky that peeks through the foliage does not recede into a deep vault; instead it behaves like a cool cushion that presses forward to meet the trees. This shallow depth keeps the viewer close and engaged, like a walker paused just inside a stand of trees. It also allows Matisse to integrate decorative interests with observed space, balancing the pull of pattern against the push of recession.

Geometry Versus Organics: The House As Counterpoint

The house’s appeal lies partly in how different it is from the surrounding vegetation. Its straight edges and simple roofline are counterpoints to the trees’ curves. The rigid postal geometry of the window or shutter—a small red rectangle—registers not simply as detail but as a formal accent, a piece of punctuation in a sentence of flowing script. The building functions like a chord change in music: the ear recognizes a new harmony, and the melody gathers energy from the contrast. Matisse engineers this tension quietly, so that the eye moves between tree and house with pleasure rather than conflict, feeling the world’s dual nature—organic and constructed—held in one frame.

The Season And The Sense Of Time

The trees appear spare, as if leafing out rather than in full summer dress. The ground shows patches of exposed soil among the fresh greens. The season feels like late winter tipping into spring. That temporal quality matters because it aligns with the cultural moment of 1919, when France was itself moving from a bare, wounded season toward renewed growth. Matisse does not literalize this with symbols; instead he lets seasonal cues—the tenuous foliage, the cool light, the tentative green—carry the mood. Time is felt as a gentle turning rather than a dramatic rupture.

Nature And Shelter: Poetic Readings Of The Motif

In a painting so pared down, the motif invites layered readings. The house can be understood as a shelter at the heart of a living maze, a human order set within, and protected by, the forms of nature. The viewer stands among the trees as if on approach, deciding whether to step forward along the path suggested by diagonal branches. There is a sense of invitation without voyeurism. The partial concealment keeps the house private, respected by the trees that both screen and frame it. This balance between openness and reserve is a hallmark of Matisse’s best work: the world is offered to the eye, but not exposed; mystery is preserved by design.

Drawing Into Painting: Contour As Structure

Matisse’s use of contour is central here. The dark outlines of trunks and foliage do not sit atop color; they interlock with it, giving structure. The method descends from his Fauvist years, where bold contour allowed color areas to radiate without dissolving the figure. In “The House,” contour quiets but remains essential. It is a scaffolding that lets the painter abbreviate interior modeling. One stroke can define a trunk’s edge while simultaneously asserting the branch’s spring. This economy results in clarity: forms read instantly, yet never stiffen into diagram.

Relations To Predecessors And Peers

Although unmistakably Matisse, the painting nods to multiple traditions. There is a kinship with Cézanne’s Provence, where houses and orchards are built from planes and strokes rather than atmospheric mist. At the same time, the softness of light and the decorative unity of surface recall the Nabis’ affection for flattened pattern. The brisk simplifications echo the Barbizon painters’ plein-air shorthand while the color restraint suggests the moderated heat of post-Fauvist sensibility. Rather than borrowing, Matisse synthesizes: a modern classicism that accepts the lessons of structure and design while safeguarding immediacy.

The Nice Period Lens: Interior Sensibility Outdoors

Matisse’s Nice period is often associated with interior scenes—the filtered light of rooms, the patterned screen, the model on a daybed. “The House” shows how that interior sensibility extends to the outdoors. The trees become a kind of natural lattice, a leafy equivalent of a decorative screen through which the eye passes toward a central object. The relationship between near pattern and far clarity mirrors the way a curtain or textile might frame a window view in his interiors. The painting thus demonstrates the continuity of Matisse’s concerns: whether inside or out, he composes spaces that are at once habitable and ornamental.

The Role Of Negative Space And The Sky

The light areas in the foliage—those irregular lobes of sky—perform crucial work. They are not merely background but active shapes, equal partners to the green clusters that surround them. By alternating these pale forms with darker leaves, Matisse creates a breathing rhythm across the top half of the canvas. The eye senses air moving between leaves. Negative space becomes positive design. This dance of void and mass is what keeps the canopy from congealing into a heavy block; instead it feels buoyant, like a mobile of cloud and leaf.

Ground, Path, And The Body Of The Viewer

The lower third of the canvas suggests a ground cut by sloped shadows and fallen branches. The diagonals lead inward at a mild pitch, inviting the viewer to imagine stepping forward. Because the ground is treated in broad swathes rather than detailed turf, it reads as a path you might feel underfoot rather than inspect blade by blade. The painting subtly registers the body of the viewer; you stand among trunks, with peripheral vision filled by bark, and look toward a clearing. This bodily orientation—close near objects, clear distant goal—charges the small scene with a sense of approach and anticipation.

Material And Method: Decisions Left Visible

As in many works from this period, Matisse leaves decisions legible on the canvas. Edges remain open where he shifts from one thought to another; a stroke that begins as gray sky may run into the contour of a leaf and be corrected by a green stroke laid on top. These palimpsests of adjustment are not errors to be hidden; they are signs of thinking in paint. They also produce tiny halos and seams that give the image its vibratory life. The house’s tiny door, for instance, sits cleanly within the wall because the surrounding grays were set first, then the red rectangle was placed decisively, leaving a crisp meeting that makes the accent ring.

Emotional Temperature: Quiet Alertness Rather Than Drama

The painting’s mood is neither melancholic nor jubilant. It hums with quiet alertness, like a morning walk when the air is cool and the day’s warmth is promised but not yet arrived. The lack of human figures increases this alertness; one listens for a door to open, for a bird to take off. Matisse earns this sensation not through narrative cues but through measured relationships—cool against warm, curve against line, open against closed. The painting trusts that a viewer’s attention, if respected, will discover its own story.

Dialogue With Earlier Fauvism And Later Cut-Outs

Compared to the incandescent canvases of 1905–06, “The House” is gentler, yet it preserves a Fauvist conviction: color areas should be self-sufficient and harmonious on their own terms. At the same time, the simplified canopy and big leaf silhouettes foreshadow the late paper cut-outs, where color and outline merge into pure shape. One can imagine the upper foliage as a sheet of paper snipped into lobed forms and pasted against pale ground. Thus the painting stands as a bridge, demonstrating how Matisse’s language could quiet without losing vitality, and abstract without abandoning the observed world.

How To Look: A Slow Circuit

The work rewards a slow circuit of the eye. Begin at the right-hand trunk, feel its columnar lift, let your gaze branch out along the limbs, then drift across the sky-holes to the opposite side. Drop down to the ground’s diagonals and follow them inward toward the house. Rest on the small red accent, then step back to take in the total pattern. This circuit echoes the act of walking around a clearing and returning to your starting point, familiar yet newly sensitized. The painting teaches a kind of attention that is portable beyond the frame: the ability to notice how simple forms—tree, wall, roof—compose themselves into a moment of calm.

Conclusion

“The House” proves how much can be achieved with modest means. A handful of colors, a few decisive contours, and a clear design yield a scene that feels both particular and archetypal. Matisse transforms a small dwelling and a stand of trees into a meditation on shelter, growth, and renewal. The painting neither dazzles with virtuoso detail nor retreats into abstraction for its own sake. It stakes out a middle ground where observation and invention cooperate. In 1919, that cooperation offered a path forward, an art capable of reconciling the world’s changes with enduring human needs. Today the canvas continues to offer what the title promises: a house—seen, remembered, and held in paint—at the center of a living world.