Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

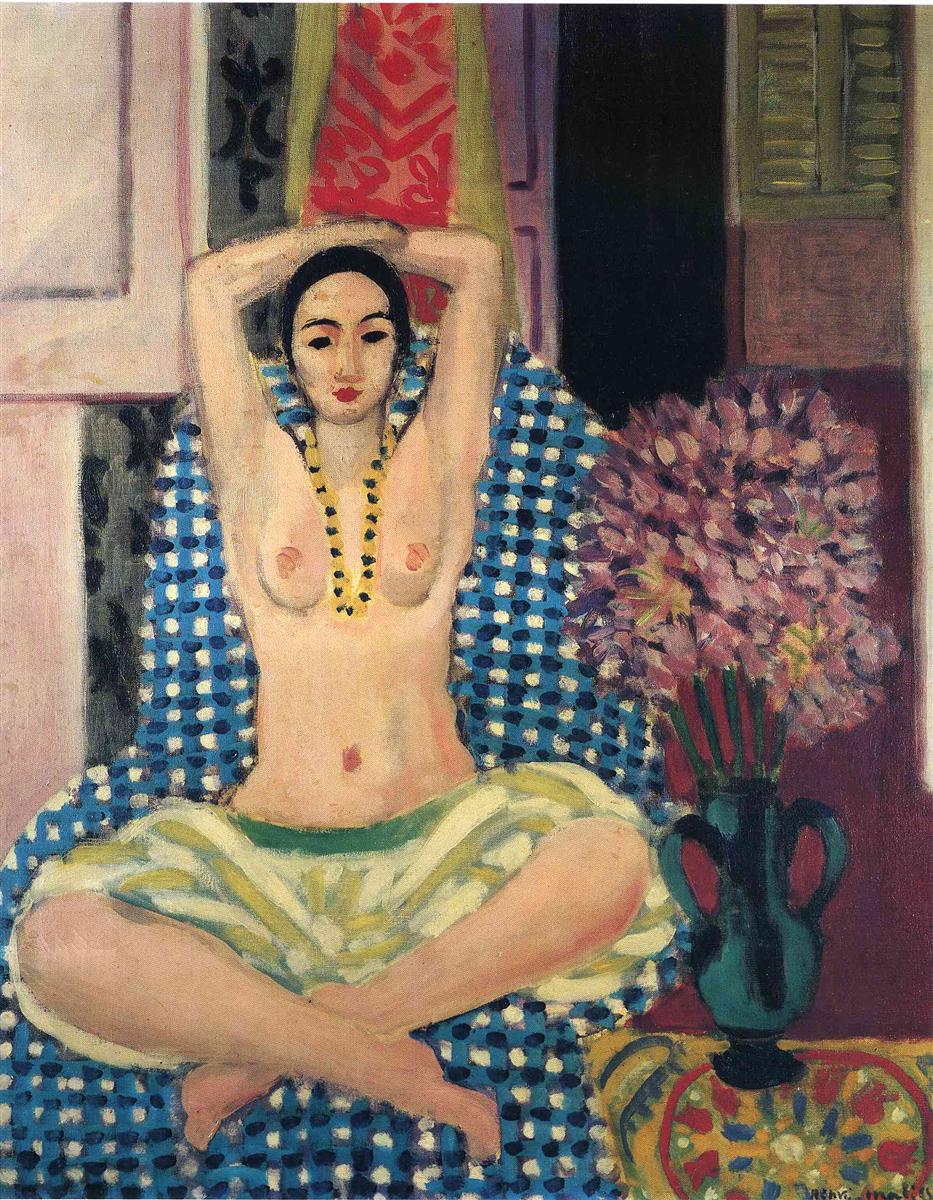

Henri Matisse’s “The Hindu Pose” (1923) is one of the clearest statements of his Nice-period vision: a poised odalisque seated cross-legged, arms lifted behind her head, centered within a shallow interior that glows with patterned fabrics, checked textiles, and floral abundance. The scene is intimate but not secretive, decorative yet disciplined. Across the canvas Matisse uses balanced contrasts—warm and cool, soft flesh and emphatic pattern, vertical hangings and a grounded seated pose—to turn a familiar studio motif into a serene architecture of color. The work reveals how, by the early 1920s, Matisse had shifted from the shocks of Fauvism to a lucid modern classicism in which figure and décor share equal dignity.

Historical Context

Painted in 1923, “The Hindu Pose” belongs to the rich sequence of Nice interiors that occupied Matisse after 1917. In those rooms by the Mediterranean, he could work from the model in steady, gentle light, staging them among screens, carpets, and flowers gathered from local markets. The odalisque theme—filtered through nineteenth-century Orientalism—offered a pretext for the nude while also legitimizing a riot of textiles and color. But Matisse’s point was not ethnographic narrative. He wanted a structure for harmony. In this painting the title references a cross-legged “Hindu” seated position, yet what matters formally is how the pose unlocks a network of compositional rhymes and pictorial rhythms.

Composition and Pose

The model sits cross-legged, ankles tucked, with both arms raised to cradle the head. This symmetrical frame—the triangle of the forearms and the base of folded legs—stabilizes the composition and directs attention to the vertical axis of the torso. The pose creates opposing forces: upward stretch in the arms, downward seated weight in the legs. Matisse nests the figure inside a large, blue-and-white checked textile that spills like a stage curtain around her, so that the human body becomes a luminous island set in a patterned sea. At the right, a tall turquoise vase full of bursting flowers occupies the same visual weight as the model’s body, confirming the Nice period’s “democracy of surfaces”: figure and still life carry equal compositional authority.

The Mirror of Patterns

Behind the sitter, a stack of hanging fabrics—soft pink, deep charcoal, and a central red band with triangular motifs—builds a vertical column that punctuates the background. These upward stripes answer the figure’s lifted arms, while the checked cloth ripples horizontally across the seat and floor to echo the crossed legs. Nothing is accidental. The checks, diagonal folds, floral mass, and banded hangings make a four-part counterpoint around the body, nudging the eye to circulate in slow, measured loops rather than darting to any one detail.

Color Climate

Color here is both mood and structure. The blue-white field of the checks delivers a cool, aerated atmosphere that keeps the room fresh. Against it, the flesh reads as warm and luminous, modeled with pale creams, apricots, and the faintest violets in shadow. The red hanging behind the head raises the temperature at the center, while the green-yellow trousers (or harem pants) provide a middle register that mediates between hot and cool. The turquoise vase and deep purple-pink bouquet at the right supply saturated anchors that keep the composition from dissipating into pastel light. Small, strategic accents—the crimson of the lips, the dark notes of the eyes, the yellow-black beaded necklace—calibrate the chromatic balance as a musician tunes a string section.

Economy of Drawing

Matisse’s draftsmanship is spare and decisive. The face is constructed with a few confident strokes: brows like quiet arches, succinct eyelids, a short planar nose, and a compact red mouth that acts as an anchor. The breasts are rendered with minimal modeling, their volumes suggested by soft temperature shifts rather than heavy shadow. Hands disappear behind the head, preventing narrative fuss and leaving the arms to read as elegant, continuous curves. The crossed feet, tucked beneath, are briefly indicated; they do the structural work of closing the triangle without demanding attention. This economy maintains freshness and keeps the surface open for color to carry expression.

Light Without Drama

As in much of the Nice period, illumination is ambient. There is no theatrical spotlight, no cascade of hard shadows. The figure glows as if light were pooled within the room’s mild air. Matisse shades with cool violets and grays that preserve chroma; the skin never dulls into brown. Because the light is even, relationships among colors—rather than contrasts of light and dark—build the sensation of depth and tactility. The eye reads the room as breathable, gentle, and calm, a climate perfectly matched to the relaxed pose.

Space as Layered Planes

“The Hindu Pose” compresses space into a set of layered textiles and objects. The checked cloth pushes forward and becomes the floor and seat in one. Behind the head, the vertical hangings read as a shallow screen; to the right, the floral still life and rug-covered table form another shallow plane. Overlap, not linear perspective, carries the sense of nearness and distance. This strategy brings the viewer close—within conversational range of the sitter—and keeps the painting honest as a surface of colored shapes rather than an illusionistic stage.

Rhythm and Repetition

The painting is musical in its repetitions. The necklace’s beads tap out a small but insistent beat at the center. The checked textile hums in a steady rhythm across the lower two-thirds of the canvas. The floral heads at right offer a trill of staccato brushmarks. The red band behind the head acts like a cymbal crash—brief, bright, and central—while the quiet verticals of shutter and hanging add a slow pulse at the edges. In this orchestra of patterns, the figure functions as a sustained, warm tone; her steady presence modulates the surrounding rhythms into balance.

The Still Life as Counter-Presence

Matisse rarely inserts still life elements as mere decoration. The turquoise vase and dense bouquet are compositional equals with the figure. Their color weight stabilizes the right side; their vertical thrust matches the model’s lifted arms; their textures—short, dabbing strokes for petals; longer, curved strokes for the vase—provide a counter-texture to the checks. The circular rim and twin handles echo the roundness of shoulders and knees. In effect, the still life serves as a second character, silent but commanding, with which the sitter shares the interior.

Ornament and Identity

The beaded necklace, a recurring accessory in Nice interiors, is more than jewelry. Bead by bead, it breaks the long plane of the torso with a dotted line that grounds the gaze at the center. Culturally, beads and the “Hindu” pose nod to Orientalist staging. Formally, they are precision tools: the yellow beads converse with the greenish trousers, while their tiny black intervals rhyme with the black marks in the hangings and the dark hollows of the bouquet. The result is neither story nor costume study but a graphic instrument that helps the painting keep time.

The Ethics of Poise

Matisse’s model meets the viewer’s gaze with composed directness—neither coy nor defiant. The cross-legged posture suggests ease rather than erotic display; the raised arms lengthen the torso and lift the chest like a quiet inhalation. In Nice-period pictures, pleasure is disciplined through balance. This canvas shares that ethos: the body is calm and available to looking, yet it is never vulnerable or theatrical. Its dignity comes from being placed within an order of harmonious relations.

Brushwork and Material Presence

Close looking reveals the tactility of Matisse’s touch. The checks are built from brisk, repeated dabs that leave micro-intervals of ground, making the fabric flicker. The bouquet is a compact storm of short, creamy strokes that never coalesce into botanical description but register as energy. The trousers are swept with longer, softer passages that glide over the knees, their pale yellow stripes skipping in fast arcs. On the flesh the paint thins and thickens with great sensitivity, letting underlayers lend warmth at the edges. The whole surface keeps a living tempo—assertive where pattern demands it, tender where skin meets air.

Dialogue with Tradition

Matisse’s odalisques echo Ingres’s linear elegance and Delacroix’s love of sumptuous décor, but they turn those legacies inside out. Line here is not cold; it’s elastic. Décor is not anecdotal; it’s structural. The cross-legged pose recalls Indian sculpture or yogic postures through the filter of European imagination, yet Matisse empties the reference of narrative and keeps the emphasis on pictorial logic. One might also hear Cézanne’s lesson in the way pattern substitutes for deep space and how a vase becomes a column of color supporting the design.

Comparisons Within 1923

Compared with “Standing Odalisque Reflected in a Mirror,” this painting forgoes spatial tricks in favor of frontal serenity. Compared with “Moorish Woman with Upheld Arms,” it is cooler and more symmetrically ordered—its center of gravity lowered by the cross-legged base. And compared with Matisse’s readers and women in yellow blouses from the same year, “The Hindu Pose” pushes décor to the foreground: the checked cloth is as important as the body, a full partner in the visual music. Across each of these canvases, however, the constants remain: ambient light, compressed space, disciplined color, and the refusal of melodrama.

How to Look, Slowly

Begin at the necklace. Let the beads establish your viewing tempo. Rise to the red band behind the head, then to the calm oval of the face and the compact red of the mouth. Drift down the arms, feeling how their arcs hold the field together. Slip along the green-yellow stripes of the trousers and settle into the blue-white checks, allowing the pattern’s rhythm to slow your gaze. Cross to the turquoise vase and up through the tight petals of the bouquet, then return to the center. Each circuit clarifies the painting’s logic: small accents govern large fields; cools steady warms; pattern supports presence.

Legacy and Relevance

“The Hindu Pose” exemplifies why Matisse’s Nice period continues to guide painters, designers, and photographers who want to reconcile decoration with clarity. It models how a dominant textile can set the room’s tempo without smothering the figure, how a limited palette can breathe, and how a single, centered pose can carry an entire composition when every surrounding color is tuned to it. Beyond influence, the painting offers a compact ethos for contemporary viewers: attention is a pleasure, repose is a discipline, and environments arranged with care can make human presence feel at ease.

Conclusion

In “The Hindu Pose,” Matisse compresses a world of decorative richness into a lucid, frontal harmony. The cross-legged body, the lifted arms, the blue-checked surround, the vertical hangings, and the turquoise vase of flowers are all tuned like instruments playing in one key. Color carries light; pattern constructs space; drawing is concise; mood is calm. As a result, the painting does not read as anecdote but as a balanced state—a sustained chord of modern beauty. Nearly a century later, its poise remains instructive and restorative: a room, a body, and a bouquet breathing in the same mild air.