Image source: wikiart.org

The Hermit and the Sleeping Angelica by Peter Paul Rubens: Overview

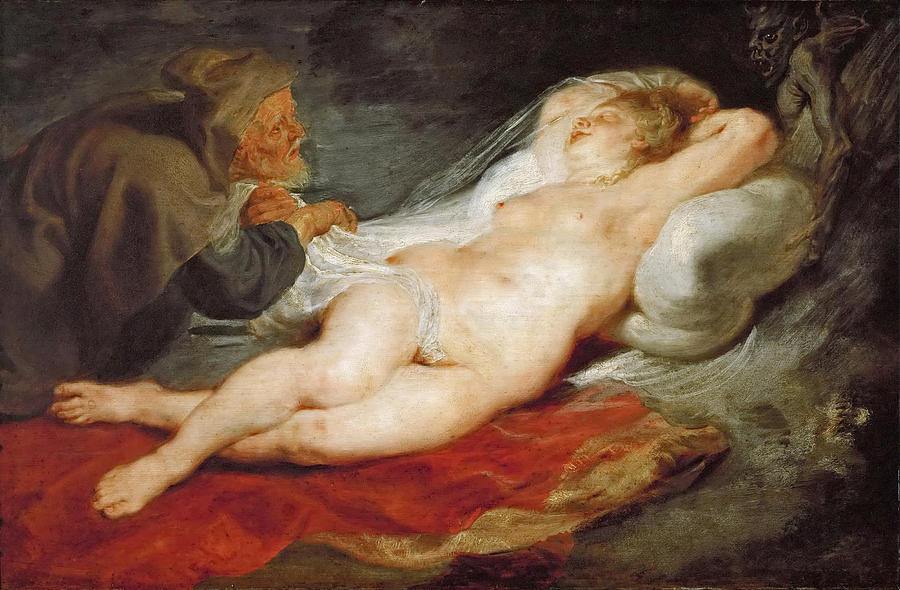

“The Hermit and the Sleeping Angelica” is one of Peter Paul Rubens’s most unsettling and provocative mythological paintings. At first glance, the canvas presents a luminous female nude reclining on a red cloth, her pale body bathed in a shimmering light that seems to caress every curve. Yet almost immediately the eye is drawn to the hooded figure at the left, a wrinkled hermit who bends close to the sleeping woman and begins to lift the veil that partially covers her. In the shadows at the far right, a horned demon peers out, its grinning face barely visible but unmistakably malign.

This mixture of sensual beauty and dark menace defines the tone of the painting. Rubens harnesses his virtuosity in depicting flesh, fabric, and expression to tell a story of temptation and moral danger. The painting belongs to a long tradition of images that draw on Ludovico Ariosto’s epic poem “Orlando Furioso,” in which the princess Angelica becomes the object of desire for knights, magicians, and hermits alike. Rubens focuses on one of the poem’s most disturbing episodes, turning it into a study of lust, vulnerability, and the thin line between reverence and exploitation.

Literary Background: Angelica in Orlando Furioso

To understand the drama of this painting, it helps to recall the narrative behind it. In Ariosto’s Renaissance epic, Angelica is a princess of extraordinary beauty whose presence incites obsession and chaos among the Christian and Saracen knights. At one point in the poem, she is rescued from danger by a supposedly holy hermit. Instead of acting as a protector, the hermit becomes consumed by desire and uses magic to put Angelica into a deep sleep. Once she lies unconscious, he attempts to undress and assault her, only to be thwarted when his own body betrays him and he cannot complete the act.

This episode is deeply troubling, and Rubens does not shy away from its discomfort. Rather than depicting the moment of rescue or a romantic encounter between Angelica and one of her admirers, he chooses the morally ambiguous instant when the hermit hovers over her sleeping body. The demon lurking in the shadows stands for the dark forces that have infected what should have been a scene of charity and hospitality. By selecting this moment, Rubens transforms a literary narrative into a powerful visual meditation on hypocrisy and the corruption of spiritual authority.

Composition and Spatial Drama

Rubens structures the composition around the diagonal line of Angelica’s reclining body. She lies on a red cloth spread across the lower half of the canvas, her head resting on a pile of pillows to the right and her feet extending toward the left foreground. Her pose twists slightly, with one arm bent over her head and the other resting near her side, creating a gentle S-curve that guides the viewer’s eye along her form. The entire composition seems to pivot around this luminous axis of flesh.

Opposite her, crouched on the left, the hermit leans in from the darkness. His hunched body, wrapped in brown monastic robes, forms a compact triangle that contrasts with Angelica’s open, flowing pose. His gaze and hands are focused on the thin fabric draped across her midsection; he pulls at it carefully, as though both fearful and eager. This line of attention draws the viewer into the forbidden space between them, intensifying the sense of violation.

The background is kept deliberately vague and murky. We sense a cavern or a dim cell rather than a fully defined interior. This lack of architectural detail pushes the figures forward and reinforces the feeling that we are witnessing something secret and illicit, hidden from the normal world. The demon’s small figure in the upper right appears almost fused with the dark wall, emerging like an embodiment of the shadows themselves.

Light, Color, and the Contrast of Flesh and Shadow

Light plays a central role in conveying the emotional atmosphere of the painting. Angelica’s body is lit as if by a soft, golden lamp, highlighting the smoothness of her skin and the rounded volume of her limbs. Rubens, famous for his depictions of voluptuous nudes, renders her with creamy tones, delicate transitions of color, and subtle reflections of light off the red cloth beneath her. Her flesh glows against the darker surroundings, making her appear both radiant and exposed.

In contrast, the hermit is wrapped in deep brown and gray tones. His face, though partially illuminated, is modeled with rough strokes that emphasize his age and weathered features. The folds of his robe fall in heavy, almost clumsy masses. Whereas Angelica’s form is painted with a sensuous, flowing brushwork, the hermit’s figure seems weightier, his very presence a burden pressing into the scene.

The red cloth beneath Angelica provides an important symbolic and visual anchor. Its warm hue echoes the warmth of her skin but also suggests passion, danger, and blood. The fabric’s loose, rippling folds create a sense of movement that contrasts with Angelica’s stillness; they seem to rustle under her body, as if the painting has caught them mid-shift. In the background, cooler grays and blacks dominate, enveloping the hermit and demon in a kind of moral gloom. The palette thus divides the painting into zones of light and darkness that mirror the inner conflict at its heart.

Angelica’s Vulnerability and Idealized Beauty

Angelica’s presentation is typical of Rubens’s female nudes, yet the context of the scene changes how we interpret her beauty. She is full-bodied, with soft curves, dimpled knees, and a slight roundness at the abdomen that underscores her humanity. Her head is tilted back, eyes closed, lips slightly parted in sleep. The pose is relaxed and unguarded; one arm supports her head while the other falls loosely, suggesting that she is entirely unaware of the danger beside her.

Rubens’s handling of the veil and the remaining cloth around her hips intensifies this vulnerability. The translucent fabric no longer truly covers her; it hangs loosely, half-pulled away, existing more as a token of modesty than an effective barrier. The hermit’s fingers, already inserted into the folds of the veil, reinforce the impression that her state of undress is not her own choice but imposed upon her.

Despite this troubling context, Rubens’s portrayal of Angelica is not humiliating. She retains dignity even in her exposed, unconscious state. The soft lighting and careful modeling of her features emphasize her innocence rather than erotic invitation. Her body becomes the site where the painting’s moral drama unfolds: a symbol of purity placed at the mercy of corrupted desire.

The Hermit as Hypocrite and Anti-Saint

The hermit in Rubens’s painting embodies the theme of spiritual hypocrisy. Cloaked in the brown habit associated with asceticism and holiness, he should represent withdrawal from earthly temptations. Instead, his entire posture contradicts his attire. He crouches low, his face close to Angelica’s body, his hands engaged in a furtive action. His expression combines greed, anxiety, and perhaps a hint of self-disgust, as though he recognizes the gulf between his vowed life and his present behavior.

Rubens exaggerates the age difference between the two figures. The hermit’s face is wrinkled, his beard white, his body shrunken. Angelica, by contrast, is young and glowing with life. This visual disparity heightens the sense of violation, turning the scene into an image of predatory behavior rather than mutual attraction.

At the same time, the artist avoids portraying the hermit as a simple monster. The hesitation in his gesture and the worry etched into his face suggest internal conflict. He is not a devil but a human being overcome by desire. This nuance makes the painting more psychologically rich. Instead of offering a straightforward denunciation, Rubens invites viewers to recognize how even those dedicated to holiness can fall prey to inner weakness when they forget the true purpose of their vocation.

The Demon and the Presence of Evil

In the upper right corner of the painting, almost hidden in the darkness, a small demon peers over the rocks. With its pointed ears, glowing eyes, and toothy grin, it appears delighted by the scene unfolding below. Its inclusion transforms the painting from a merely human drama into a spiritual battlefield.

The demon functions as a visual metaphor for temptation and the external forces that encourage sin. It seems to whisper encouragement to the hermit, feeding his fantasies and pushing him toward action. Its diminutive size underscores the irony that such a small, shadowy presence can exert a powerful influence on human behavior.

By separating the demon from the main action spatially, Rubens implies that evil does not always appear at the center of our attention; it often lurks at the margins, insinuating itself through suggestion rather than overt command. The viewer, noticing the demon after first focusing on the human figures, experiences a delayed realization of just how corrupted the atmosphere is. What began as a tense but humanly understandable moment acquires a darker, supernatural dimension.

Tension, Voyeurism, and the Role of the Viewer

One of the most challenging aspects of “The Hermit and the Sleeping Angelica” lies in the way the painting implicates the viewer. We, like the hermit, are looking at Angelica’s exposed body while she lies unaware. The composition places us in a position slightly behind and above the hermit, as though we share his vantage point.

This creates an uneasy sense of complicity. The painting offers the visual pleasures of a beautifully rendered nude, yet it frames those pleasures within a narrative of exploitation. Rubens seems keenly aware of this tension. He uses it to question the viewer’s own desires and the ethics of looking. Are we simply appreciating artistic skill, or are we, like the hermit, indulging in a gaze that the subject has not consented to?

At the same time, the painting’s storytelling and moral cues guide us toward sympathy with Angelica rather than the hermit. The demon’s presence, the hermit’s furtive gesture, and the contrast between his dark robe and her radiant flesh all mark his actions as wrong. By recognizing this wrongness, the viewer can distance themselves from the hermit’s intentions even as they share his line of sight. Rubens thus uses the medium of painting to explore the complex interplay between representation, desire, and conscience.

Rubens’s Treatment of Mythological Eroticism

Rubens often explored sensual themes in his mythological works, but this painting stands out for its troubling ambiguity. In many of his other nudes, eroticism is paired with mutual desire or triumphant celebration: dancing nymphs, joyful lovers, or goddesses basking in their own beauty. Here, however, the erotic elements are intertwined with vulnerability and an imbalance of power.

This difference reflects the specific narrative of Angelica and the hermit, yet it also reveals Rubens’s willingness to tackle difficult subject matter. He does not romanticize the hermit’s actions or present the scene as harmless fantasy. Instead, he captures the unease of a moment where desire crosses into violation. The viewer feels both the attraction of the nude and the discomfort of the surrounding circumstances.

In doing so, Rubens participates in broader Baroque discussions about the relationship between body and soul, virtue and vice. The painting suggests that beauty can become a stumbling block when those who encounter it lack self-control or spiritual grounding. At the same time, the work celebrates the resilience of innocence: Angelica’s calm, untroubled expression and the soft light enveloping her hint that she remains untouched by the darkness encroaching around her.

Significance and Legacy of The Hermit and the Sleeping Angelica

“The Hermit and the Sleeping Angelica” occupies a complex place within Rubens’s oeuvre and within the larger history of European art. It demonstrates his mastery of anatomy, texture, and expressive characterization while also pushing viewers to confront the moral implications of what they see. The painting is both visually sumptuous and ethically challenging.

For modern audiences, the work resonates strongly with contemporary conversations about consent, power dynamics, and the objectification of women. Rubens’s depiction, though rooted in a literary source from the sixteenth century, feels disturbingly familiar in its portrayal of a vulnerable figure subjected to the unwanted gaze and touch of someone who should protect her. The presence of the demon amplifies this theme, suggesting that such abuses are not merely personal failures but symptoms of a broader moral disorder.

At the same time, the painting’s artistry remains undeniable. The fluid brushwork, the warm glow of flesh, the subtle handling of light on fabric and skin, and the carefully orchestrated composition all testify to Rubens’s genius. By wrapping a difficult narrative in such compelling visual beauty, he ensures that the viewer cannot easily turn away. Instead, we are drawn in, forced to think about what is happening and why it matters.

Ultimately, “The Hermit and the Sleeping Angelica” is a work that refuses simple categorization. It is not a straightforward erotic picture, nor is it a purely moralizing sermon. It is a complex, layered meditation on desire, hypocrisy, and the vulnerability of the human body in a world where spiritual ideals are often betrayed. Rubens invites us to reflect on the responsibilities that come with looking, the fragility of innocence, and the constant tension between light and shadow within the human heart.